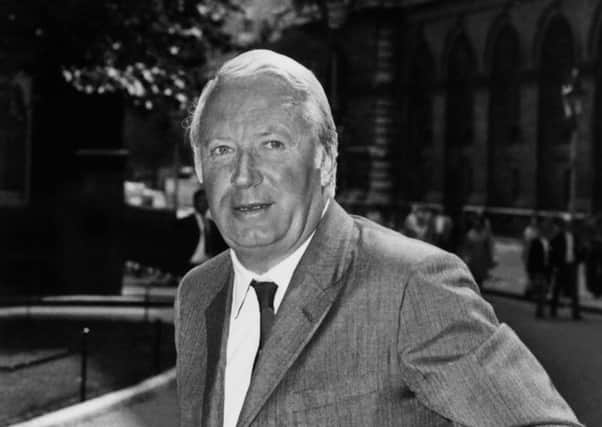

Dani Garavelli: Heath inquiry had to prove the police cared, if nothing else

When Wiltshire chief constable Mike Veale claimed the two-year inquiry into Edward Heath showed police would pursue allegations of child sex abuse “no matter how powerful the suspect”, he seemed to be wilfully missing the point.

As with Jimmy Savile, Cyril Smith and Greville Janner, the former prime minister was not properly investigated until death (or in Janner’s case dementia and then death) had stripped him of his last vestige of influence; by the time most of his alleged victims filed their complaints, he was beyond the reach of the criminal justice system.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFar from being a “watershed” moment – or a turning point in the history of child sex abuse cases – Operation Conifer has proved to be the worst of all possible worlds. Despite the 1,580 lines of inquiry explored and the £1.5m spent on uncovering the truth, we are no closer to establishing whether or not Heath preyed on young boys and men.

All Wiltshire Police can tell us is that, of the 40 allegations it investigated, seven would have met the threshold for him to be interviewed under criminal caution. We will never know – can never know – what responses the politician would have given under interrogation; or if, without forensic or DNA evidence, the case would ever have made it into a court room.

If Heath was innocent, then his reputation has been tarnished without him ever having had the chance to defend himself; if he was guilty, then those whose lives he ruined will never see him held to account. This outcome falls well short of ideal.

Last week, Lord Macdonald, the former director of prosecutions, said that far from patting itself on the back, the force should be ashamed. “The bar for interview is low in most investigations, as low as the police want it to be and, in the case of a dead man, virtually nonexistent,” he said. “They are covering their backs at the expense of a dead man.”

Personally, I think Macdonald is being overly harsh; in the febrile atmosphere that has flourished post-Savile, Wiltshire Police were in an impossible position. Now historic cases of child sex abuse are high up the agenda, it’s to be expected alleged victims, dismissed for decades, will finally come forward. When they do, the police have no choice but to launch a belated inquiry which – by virtue of the time passed and the absence of the suspect – is likely to prove inconclusive.

Furthermore, having carried out the investigation, what else can the force do but publish its views even if, as Lord Macdonald suggests, they are meaningless as the vast majority of inquiries would not meet the threshold for questioning? Sir Cliff Richard was questioned under caution, but the case against him was dropped without charge.

Add into the mix an alleged fantasist, known only as Nick, who is accused of inventing lurid stories of a murderous paedophile network, including Heath, operating at Westminster, and there is as much likelihood of gaining clarity on what happened as there is of Theresa May holding on to her job until the next party conference

The police are constantly caught between doing too little, and being accused of a cover- up, and doing too much and being accused of a witch-hunt, as has happened in relation to Heath. Veale has rightly apologised for making an appeal for victims to come forward on the steps of Heath’s former home in Salisbury. But his force has demonstrated some courage too, ploughing on in the face of mounting pressure. How can we tell – even now – if the furore over its perceived heavy-handedness was justified or symptomatic of an ongoing establishment reluctance to have its equilibrium disturbed?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLet’s look at what light this investigation has shone on Heath’s activities. Of the 40 allegations investigated, 33 were dismissed as not credible; six of these involved satanic and ritual abuse, while five involved him carrying out serious crimes including murder on board yachts.

Although Heath owned five yachts, all called Morning Cloud, between 1969 and 1984, officers found no supporting information or credible evidence to support the disclosures, and there were no missing boys.

The seven allegations that would have merited interview under caution involved five boys and two men and took place between 1961 and 1992.

The inquiry did establish that some of the arguments put up in Heath’s defence were red herrings. Officers spoke to witnesses who confirmed the former Prime Minister had been sexually active at some points in his life (some supporters had insisted he was asexual) and that he was often out and about without his protection officers (some supporters had implied they were omnipresent). But of a systematic establishment cover-up, it found no evidence (though it admitted it couldn’t investigate this aspect of the case thoroughly as it fell outwith its remit).

Other historic abuse inquiries have been more revealing: no-one now doubts the scale of Savile’s offending or Cyril Smith’s, and we have a better understanding now of the way they were able to operate in plain sight as those in authority turned a blind eye.

But there is still something deeply unsatisfactory about evidence that will never be tested, an ambiguity that will never be definitively resolved and crime allegations that will go forever unanswered.

Despite my reservations, however, I believe it was important for Heath to be rigorously investigated. However inconclusive, the inquiry helps establish the narrative that victims are now being taken seriously. Only by demonstrating they are prepared to investigate every claim – however apparently far-fetched – can police officers regain the trust they squandered during cover-ups in the 60s, 70s and beyond.

Once people adjust to the cultural shift, and start to believe child sex abuse is no longer being swept under the carpet, we should start to see more contemporary cases, involving still-living public figures, filtering into our courts. When that happens police forces like Wiltshire’s will have the chance to demonstrate they truly are committed to pursuing suspects, “no matter how powerful”, without fear or favour.