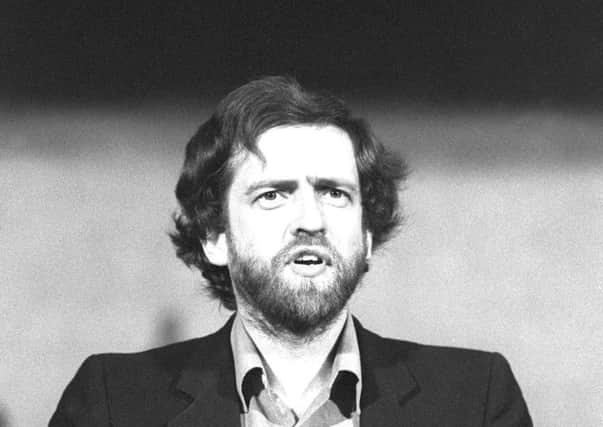

Brian Monteith: Jeremy Corbyn has some explaining to do over Czech spy meetings

Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour Party has some explaining to do.

When one paper breaks a story that in the mid eighties he was meeting with a Czechoslovakian diplomat who was later deported for spying it might be seen as unfortunate. It might be denied as innocent. When a second paper runs the story but with more detail it encourages thoughts that there may indeed be some grounds to question what was behind the meetings.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen a third paper expands the original story to now include fifteen Labour MPs, including not only the current Labour Leader but the Shadow Chancellor and Ken Livingston then the reasons for any connections with diplomats of a Warsaw Pact power need a full explanation. Simply denying money changed hands does not answer why there might have been any meetings in the first place.

Regular supporters of Labour are no friends of communism; they are not now and were not back in the eighties. Labour voters could be serving in the armed forces, they could have been working in our intelligence and security services, the Foreign Office and Ministry of Defence. They would however have no sympathies with the rulers or representatives of countries that formed the Warsaw Pact. For politicians it is different, for politicians what they say and how they act tells us what they think, what they believe in and how they might use power if government office were to be given over to them.

To consider the meetings of Jeremy Corbyn with the spy Jan Sarkocy we need to remember the context of those times.

Nearly twenty years before, in 1968, Czechoslovak communist leaders attempted liberal reforms – called the Prague Spring – only for the Soviets to send in the tanks to brutally crush it. By the eighties fresh attempts of encouraging liberal democracy were being attempted in Poland, through the trade union Solidarnosc movement. The Soviet leaders feared a violent response from Polish workers if they tried military intervention, their solution was to impose a new Polish President, General Wojciech Jarulzelski, who quickly introduced martial law.

The demands for reform in Poland did not, however go away, and they were soon being heard in Hungary, Bulgaria, East Germany, Rumania – and Czechoslovakia. The communist rulers of Czechoslovakia were resisting change and in the forefront of that resistance was their reviled Secret Police, the StB, with operatives at home and in the diplomatic missions, such as in London.

There could be no doubt that any British MP meeting with representatives of the Czechoslovakian embassy would be the subject of reports sent back to Prague, and if useful, Moscow.

In the changes that were being played out the new hope for change in the Soviet Union, its President Mikhail Gorbachev, had already communicated privately as early as 1985 that there would be no more Soviet military interventions. Instead the Eastern Bloc nations would be free to determine their own destiny – to choose capitalism or socialism. In November 1989 the Velvet Revolution took place and Czechoslovakia chose democracy, and with it a shifted towards capitalism.

When one looks back at that period, especially with the help of the copious and detailed records of the Soviet Union and its satellites that become available every year, we can now contend figures such as Gorbachev were already more supportive of reform than British Marxists such as Jeremy Corbyn.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhile Corbyn was meeting Czechoslovakian diplomats representing some of the few remaining hawks in the Warsaw Pact, Gorbachev was meeting Reagan, Bush and Thatcher in an attempt to convince them “perestroika” (listening) and “glasnost” (openness) would bring Soviet reforms and thus strengthen the cause of peace.

So what were the reasons for Corbyn’s meetings with a cold war spy? What did he think he could achieve? Was it ignorance, naivety or both? Supporters of Corbyn may think the meetings amount to nothing, but it is surely by his actions that we as electors are able to hazard a guess whether or not he is fit to be Prime Minister and what his subsequent judgements might be like.

Unfortunately for the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn has a record of being on the wrong side of arguments, especially when it comes to international affairs and security issues.

Corbyn’s association with the cause of the IRA and its supporters is well documented and includes refusing five times in a BBC interview to condemn the IRA’s murders. Only two weeks after the IRA’s Brighton bombing that resulted in the direct deaths of five people, Corbyn invited convicted IRA bombers to the House of Commons. He was also heavily involved with the magazine, London Labour Briefing, that carried a reader’s letter praising the Brighton bombing for its audacity and which included the line “what do you call four dead Tories? A start”.

He has said that the Falkland’s War was a “Tory plot to keep their money-making friends in business” despite the then Labour leader Michael Foot backing deployment of the Falklands Expeditionary Force. He has since suggested open talks with Argentina with no right of self-determination for the Falkland Islanders.

On the Yugoslavian civil war Corbyn opposed NATO’s campaign to save Kosovo but also denied the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic had committed war crimes and denied there had been any genocide there.

In Middle East politics Corbyn called recognised terrorist organisations Hezbollah and Hamas his “friends” at a reception he hosted inside the House of Commons and has taken appearance money from Iranian Television after Ofcom banned it for filming the detention and torture of an Iranian journalist. Such behaviour has only encouraged greater belief that he is willing to associate with anti-Semites, such as taking tea on the House of Commons Terrace with Raed Salah, a man imprisoned for anti-Jewish racism and violence.

More recently Corbyn’s worldview has led to further misjudgement, praising Venezuela’s socialist policies in 2015 as “a cause for celebration” while the humanitarian charity Caritas reports 41 per cent of Venezuelans are now feeding off waste food and malnutrition amongst children climbed from 54 per cent to 68 per cent between April and August last year.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe reports of Corbyn’s meeting with foreign secret agents follow a pattern that, at best, suggest poor judgment, but whatever the motive, demonstrate a repeated association with people that have wished Britain and its people harm. Jeremy Corbyn needs to explain himself if the doubts about his fitness for office are not to grow.

• Brian Monteith is a director of Global Britain