Bill Jamieson: Don't panic '“ just recall how wrong the pound and markets were

What credence, then, can we attach to the predictions of a UK-wide recession as a result of the vote to leave the EU?

For businesses large and small, a deep void of uncertainty has set in. This was a referendum campaign dominated by dire warnings of economic pain and loss. The political fall-out has been momentous. And forecasts of recession have added mightily to the mood of nervous apprehension across business.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLittle wonder, as soon as the likelihood of a Leave result became known, sterling plunged, falling at one point to $1.32, a collapse of more than 10 per cent and a low not seen since 1985. The FTSE 100 Index tumbled by more than 8 per cent before settling later in the day for a loss of 5 per cent.

Making matters worse for forecasters now is deep political uncertainty, both at home and across the Continent. Who will succeed David Cameron as prime minister? And what of an early change in the chancellorship, together with the prospect of another fractious Scottish independence referendum?

On the Continent, French and German stock markets tumbled more heavily than London on fears that Eurosceptic parties have been given a powerful boost ahead of pending elections.

Surely all this sets the seal on a recession outcome? Such would be the understandable conclusion. But we are in dangerous terrain here. Such conclusions need to be tempered by recognition of the extreme volatility currently on display.

All the more reason, surely, to bear in mind the fallibility of prediction. A Remain forecast that seemed so credible as to drive up the pound and the equity markets right up to the close of the voting stations was instantly shattered when the first results came in.

That the markets got it so wrong may be a more reliable explanation of this tumult than concerns over recession: the immediate need of investors to close down and sell their currency and stock market positions. Markets are also notoriously prone to over-shooting. And it is not inconceivable that over the coming months, should a modicum of global growth be sustained, nerves will settle and a “corrective correction” will have set in.

That said, a period of instability is inevitable. A lower pound will mean higher input costs for manufacturers. And the Leave vote may make the UK a less attractive place to invest in until the immediate uncertainty has lifted.

We should also bear in mind that a persistent concern of business and investors this year has focused less on the outcome of the UK’s referendum vote than on the health of the global economy and the prospect of a worsening slowdown.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEuropean economies are critically dependent on continuing quantitative easing by the European Central Bank. Japan is still struggling to break free from three decades of stagnation. China slowdown worries persist.

Quite how long it will take for nerves to settle critically depends on early clarification at Westminster on what fiscal measures may be taken to steady business and investor confidence.

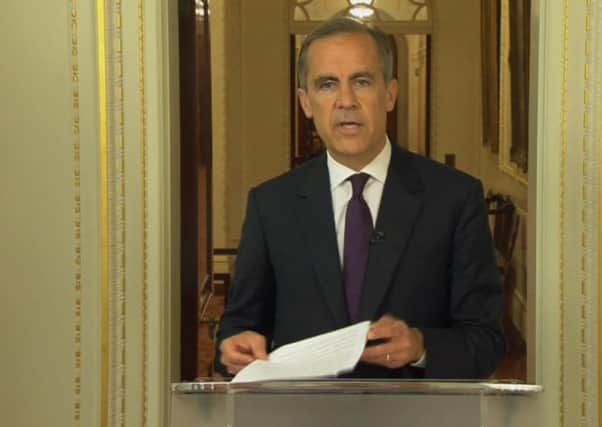

The announcement by Bank of England governor Mark Carney on Friday morning that the Bank stands ready to provide more than £250 billion of additional funds provided some reassurance. The capital requirements of our largest banks, he added, are now ten times higher than before the crisis, raising more than £130bn of capital, and they now have more than £600bn of high-quality liquid assets. This gives the banking system the flexibility it needs to continue to lend to UK businesses and households.

But much more will be needed to steady nerves and promote stability. Here the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland (ICAS) has lodged no fewer than 20 questions that the UK government now needs to address as a matter of urgency. Among them are what immediate measures it will take to minimise the impact of Brexit on the economy, jobs and efforts to restore the public finances.

When will the emergency budget promised by the Chancellor take place – if at all? How will the government help to continue to attract foreign direct investment, given the uncertainties? What trading arrangements and tariffs will the UK be able to negotiate with the EU and other countries, and how long will these take to agree?

There are many more in that vein – and I suspect few have any ready answers.

Meanwhile, what are the pundits forecasting now? Howard Archer, economist at IHS Global Insight, is slashing his UK GDP growth forecasts to 1.5 per cent (from 2 per cent) for 2016. For next year he is predicting just 0.2 per cent (from 2.4 per cent) and for 2018, 1.3 per cent (down from 2.3 per cent).

“Major economic and political uncertainty,” he writes, “will be a fact of life for some considerable time, likely weighing down markedly on business and household confidence and behaviour, so dampening corporate investment, employment and consumer spending.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland, which has recently been under-performing the UK, may struggle to reach even these levels, while the possibility of another independence referendum will not be welcomed at all by business.

Douglas McWilliams, head of the Centre for Economics and Business Research, says that in this new world we have entered, his best guess for GDP growth this year is also for around 1.5 per cent. But he is more optimistic about next year. “Growth will grind almost to a halt but consumer spending may just be strong enough to prevent a recession.”

Looking further ahead, he believes 2018 “could be quite a strong year as exports lead a recovery – and new trade arrangements start to come into place. Tentatively we are talking about GDP growth of 2.5 per cent.”

But whether it’s doom or gloom, bear in mind my caveat about predictions made in tumultuous times.