100 Weeks of Scotland: Coal industry

Week 72

In 1980, coal dug by a miner in Ayrshire, or Fife, or Midlothian could fuel the furnaces of Ravenscraig, which in turn could supply the steel to build the cars of Linwood and the ships of Clydeside. A dozen years later, the fires of Ravenscraig had burned for the last time and the final car had long since rolled off the production line at Linwood. Ships would continue to slowly slip in to the Clyde but the glory days of shipbuilding were a faded memory. During the 1980s, as Thatcherism rode roughshod over anything where the profit margins were not high enough, heavy industry in Scotland would see its iron heart ripped out, and it was the coal industry that was hit hardest.

I wanted to take some photos to mark the anniversary of the strike and quickly discovered that almost nothing remains of the coal industry today. The collieries have long since been closed and landscaped over with new developments. Trying to find anything above ground, other than that preserved by mining museums is almost impossible.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI set off early one morning for Ayrshire to see what remained of the industry there. The road from Edinburgh, once past Lanark, heads southwest through a high country past the old mining villages of Glenbuck and Muirkirk. The small community of Lugar, which once boasted a huge ironworks (cold and closed for close on a century now), soon slips by and before long I am on a hilltop in the Ayrshire town of New Cumnock. Uneven concrete steps, broken and cracked, lead nowhere up gentle slopes.

Potholed streets circle aimlessly beneath damaged electric lighting. The pit closed, the people left and the houses were bulldozed. This is a housing estate with no houses, with no people.

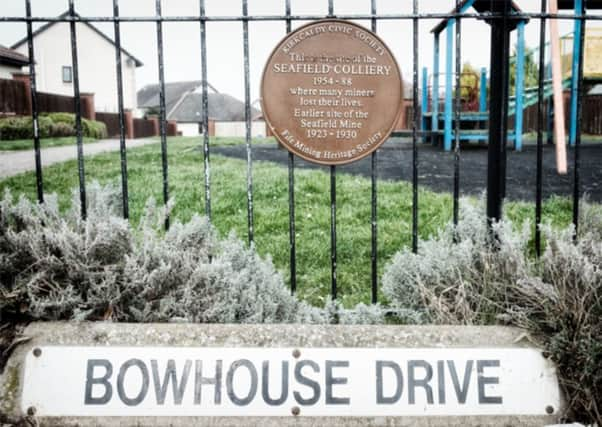

I headed over to Fife to visit the location of one of the few collieries I actually remember. The Seafield pit near Kirkcaldy was a major landmark when I was a child, situated as it was a mile or two from my aunt and uncles home in Kinghorn. I hadn’t been on the road from Kinghorn to Kirkcaldy in decades and everything was as it had been, until, as the road passes under the railway line, the view ahead is no longer of the imposing colliery buildings, but instead a newly constructed housing estate. All that remains of the Seafield mine is a small blue plaque, placed low on a metal fence surrounding a children’s play park. When the mine opened in 1960 it was claimed it would have a working life of 150 years. It lasted 28. The coal is still there, millions of tons of it, snaking out under the Firth of Forth.

It is Saturday afternoon in Danderhall Miners Welfare & Social Club. Outside a local football team struggle against a near hurricane wind. Inside, in the bright and sunlit bar a few ex-miners gather. It had been a big night the night before at Prestonpans Miners & Social Welfare Club – a large gathering of ex-miners, councillors and MSPs. John Barr, whose portrait I took, spoke to me of his time working at Monktonhall Colliery until it closed and then Longannet Colliery until it also closed. He had been, and now probably always will be, the last working miner in Danderhall.

What surprised me was just how little of the infrastructure of the coal industry in Scotland remains. It has been almost entirely wiped off the map. Although the buildings and the pit wheels may have been demolished years ago, deep below the ground the coal they were built to extract is still there – and above, the miners are too.

• Alan McCredie began the ‘100 weeks of Scotland’ website in October last year, and it will conclude in Autumn 2014. McCredie’s goal is to chronicle two years of Scottish life in the run-up to the independence referendum.

Alan says ‘one hundred weeks...’ is intended to show all sides of the country over the next two years. On the site, he says: “Whatever the result of the vote Scotland will be a different country afterward. These images will show a snapshot of the country in the run up to the referendum.

“The photos will be of all aspects of Scottish culture - politics, art, social issues, sport and anything else that catches the eye.”

Follow the project at 100weeksofscotland.com. You can also follow Alan on Twitter @alanmccredie.

• All pictures (c) Alan McCredie/100 weeks of Scotland