Why Nicola Sturgeon is right to open a foreign office in Denmark - Stephen Gethins

This was not a major scoop. The Scottish Government, like other governments that are not fully independent, have several offices around the world that help promote trade and other links. It was surprising that Scotland did not have such an office given the strong trading and other links with our neighbours to the east.

A few days ago, the First Minister got round to opening that office, causing something of a stir back home with some ill-informed talk of ‘pretendy embassies’.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe criticism missed the point the SNP is not the first Scottish party of government to have opened overseas offices, with both the Conservatives, in the pre-devolution era, and the Labour/Liberal Democrat administration, in the early years of the Scottish Parliament, having opened overseas offices.

If any Danes were following the stooshie, they would have been forgiven for wondering what the fuss was about. Both Greenland and the Faroe Islands, whilst part of Denmark, enjoy significant international powers. The Faroese were among the first to sign their own post-Brexit trade deal with the UK and the Greenlandic are even party to a defence treaty with Denmark and the USA.

They are not unique. Around Europe and the rest of the world non-sovereign governments invest heavily in their foreign policy footprint. This helps promote their brands, economic growth, educational opportunities, cultural links and political influence.

Research published in today’s Scotland on Sunday shows that not only do many similar entities to Scotland invest heavily in their international work, but that comparatively Scotland underspends in this area.

All politics may be local, but the world is incredibly interdependent and linked. The cost-of-living crisis affects communities across Europe and the wider world. That means it is more important than ever to try and bring down trade barriers, promote local interests and provide security, not just militarily, but also in areas such as food and energy.

This investment is even more pressing for Scotland than it is for many states. The UK’s decision to leave the EU and put-up trade and other barriers to its most important partners in the rest of Europe has made the country poorer and exacerbated the cost-of-living crisis. Scotland is now part of a state that is isolated among its natural partners, getting poorer and less able to tackle the crisis affecting households and public finance alike.

Scotland therefore needs to work harder than ever to maintain its international links. That should be about promoting Scotland’s distinctive brand to boost business and trade as well as exploring educational opportunities lost when the UK left the EU. It is also a chance to harness other ties such as those with our vast and widespread diaspora.

Far too often we debate the cost of a minister’s travel rather than scrutinising the impact of their policies. At a time of unprecedented crisis, we cannot afford that kind of parochialism. It is time that we gave Scotland’s international affairs the level of debate and investment it deserves.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

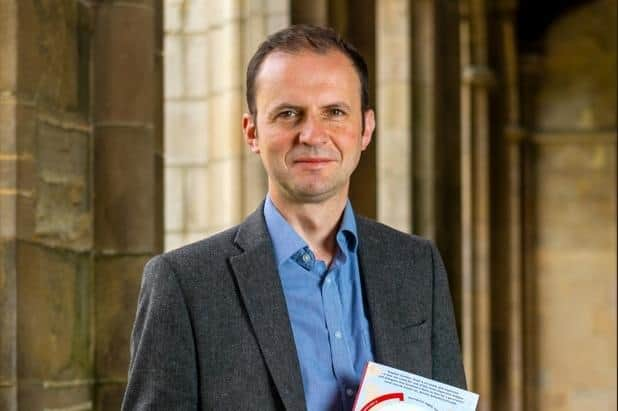

Hide Ad- Stephen Gethins is a professor of international relations at the University of St Andrews. The second edition of his book Nation to Nation: Scotland’s Place in the World (Luath Press) is available online and in bookshops

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.