The bold, young traveller who devoured our 18th Century Edinburgh - witty women, brandy punch and all - Susan Morrison

In the late 1760’s, young Edward Topham left uni, took a gap year and did a bit of travelling. He mooched about Europe on the traditional Grand Tour, probably taking in a bit of Italy, a stay in Paris and possibly a small German principality or two, then on his way home in 1774, he decided to take in Edinburgh.

He stayed for six months. No sooner had he arrived than he started sending letters, and when he re-read them, he thought, I’ll publish these, and we should be grateful he did, because his observations are a delight. Once you get over his habit of calling us ‘Scotch.’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe’s impressed. Edinburgh, he notes, is built on 'immense hills’ which make the “views uncommonly magnificent”, but “very fatiguing for walking”. The same complaint tourists have today.

He’s got an eye for detail. The New Town is under construction, and he took a keen interest in the building. The pavements will be knockout. They’re being laid with granite from nearby quarries, which he huffily notes, used to be the very stuff intended for the streets of London.

This New Town will be a revolution in Scottish living. For the first time, those urban Old Town Scots who can afford it will have what he calls ‘a house to themselves’. In the Old Town warren of wynds, stairs and closes the wealthy literally lived on top of the poor. The higher up the building, the fresher the air, away from the appalling stench of the streets.

Technically, the chucking of waste from the windows of the Old Town had been banned by the city, but, in typical Scottish fashion, no-one gave two hoots about that. The fluid still flew and the solids still landed. Edward laments that many an elegant suit of clothes had been spoiled and even the famous Dr Johnson himself wrote that in Edinburgh “many a full-flowing perriwig moistened into flaccidity".

Edward would not have given Edinburgh lodging a good review on Tripadvisor. He first tries to get a lodging house at the Pleasance, but, like trying to get accommodation during the Fringe, it turns out to be difficult. The only room available, he’s told, has just been vacated by 20 Highland drovers who have been eating potatoes and drinking whisky all night. Willing to bet that wasn’t all they were doing. Tatties and booze can play havoc with the digestion if you over-do it, and this in the days when en suite meant a bucket in the corner.

To be fair, the city is still adjusting to its new role as a tourist destination. Travellers are still a novelty, if you discount the drovers. Everyone he meets is downright nosy, constantly asking what he and his friend are doing there. He quickly finds that an invitation to join a Scottish family at dinner is tantamount to being adopted by them, and subjected to a polite interrogation over the soup. Are they students, here to study law, medicine or divinity? Some suppose the new arrivals to be hairdressers, or worse, actors.

One pious lady at a social gathering announces outright that he’s a spy and should leave town at once. Come on. We’ve all got that embarrassing auntie.

Young Edward has his head seriously turned by the ladies of the city, who he says are lovely until they hit twenty, when they turn large and lusty. An introduction to a belle of the New Town brings out the Burns in him. He was bowled over by “the fragrance of her breath, the downy velvet of her skin, and pearly enamel of her teeth”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe girls are beautiful and smart. Their conversation is sparkling and witty, and even more astounding, at dinner and in company they match the men drink for drink and aren't shy of giving their opinion.

Like many a lad on holiday, there is a romance. It’s only hinted at, but he does find himself being invited out by one of these forward city girls. It turns out to be more of a group event than the intimate date he had perhaps anticipated, because our bold boy has been invited to an Oyster Cellar.

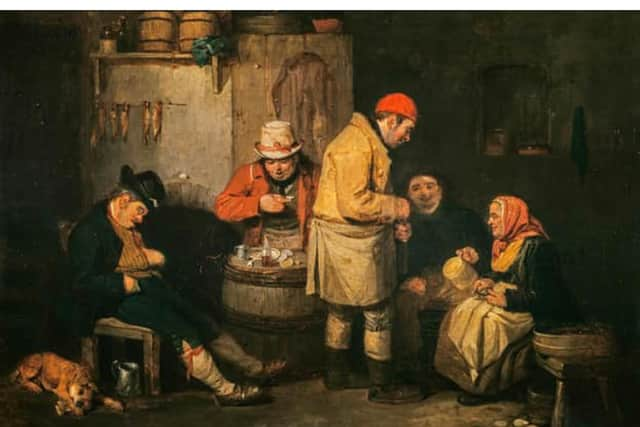

He's ushered into an underground room with a gaggle of ‘brilliant’ ladies and gentlemen. Huge bowls of oysters are put out on a vast table and the ladies drink order is taken. No wine for these gals. The girls, who ‘always love what is best, fixed upon brandy punch’. Women and cocktails have had a long history. The evening rapidly becomes what Edward describes as ‘lively’. The conversation is fast and witty and the women are right in there with the repartee.

When the cut and thrust of the chat gets boring, to his astonishment, it's time for the dancing. The ladies lead the company to dance reels, their favourite dance, which they performed with great agility and perseverance.’

It’s all going terrifically well until “One of the gentlemen, however, fell down in the most active part of it, and lamed himself ; so the dance was at an end for that evening.” There’s always one, isn’t there?

Edward visits gardens, funerals, churches and courts, and watches an execution in the Grassmarket. He even has an encounter with a Highland family who speak no English, but extend a warm welcome to him when he is lost in the hills. No nation, he says, is as excellent at hospitality as the Scotch.

When he mentions leaving Edinburgh he seems sad to leave us. We should thank him for his visit. He gave us a lovely leaving present. To paraphrase Burns, it’s quite the gift to ‘gie us To see oursels as ithers see us!’.