Susan Dalgety: US state dubbed '˜almost heaven' has worst fatal OD rate

Almost heaven is the new slogan for the West Virginia tourism campaign.

It is also a line from John Denver’s famous ditty, ‘Country Roads, Take me Home’, which has been stuck in my ear for the last few days. Worse, I occasionally burst into song.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe are in the Mountain State, one of the most beautiful parts of these United States.

There are soaring mountains as far as the eye can see, covered with millions of trees in every shade of green. It has more than 50 named rivers, 1,400 miles of hiking trails and ski resorts to rival Aspen.

West Virginia is an outdoor holiday paradise. It really is almost heaven.

It is also one of the poorest states in America, vying for bottom place with Mississippi and Arkansas.

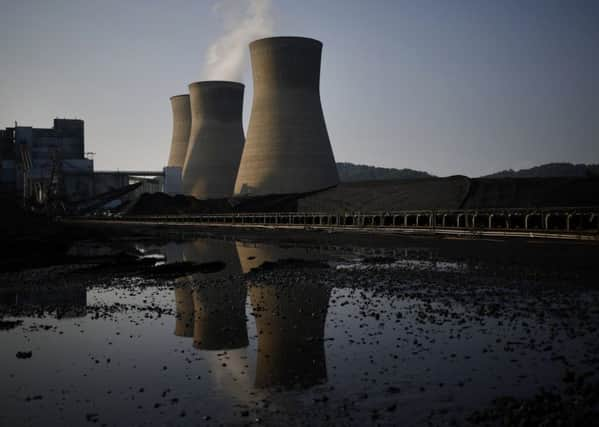

The black gold that the state is, literally, built on, and which powered its economy and America’s industry for more than a century, has lost much of its glitter. The coal industry, which at its height employed 125,000 people, now provides only 14,000 jobs. But even these are at risk, as the natural gas industry takes hold and coal becomes a tarnished relic of the past.

The state’s biggest employer is the supermarket giant Walmart, where old men with walking frames work alongside teenage girls and grandmothers.

No-one wants coal these days. Except of course the hardy folk of West Virginia and their President.

If Trump belongs to any state, it is West Virginia. He won his biggest share of the vote here in November 2016, convincing more than two thirds of the electorate with his promise to bring back coal jobs. The result was the biggest presidential victory in the state’s history.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis share of the vote beat even that of Abraham Lincoln in 1864 – and Lincoln was the man who agreed to West Virginia’s statehood in the early days of the civil war.

Little wonder then that Trump keeps taking those country roads back to West Virginia when Washington gets too uncomfortable for him.

He feels at home here among the working class, mostly white, mountain people, many of them descendants of the Ulster Scots who emigrated to the USA in the 1700s.

Even West Virginia’s Democrat senator Joe Manchin is a Trump ally, claiming he may endorse Trump for re-election in 2020.

The fact that Manchin is facing a fierce fight to hold on to his senate seat this November is only part of the reason why he backs Trump. He is a West Virginian first, a Democrat a distant second.

And the state’s governor, Jim Justice, who was elected two years ago on the Democrat ticket, switched sides last August to become a Republican. His conversion to Trumpian politics happened, where else, but at a Trump rally with his new best friend by his side.

“I can’t help anyone being a Democrat,” explained the 67-year-old governor, a billionaire whose family made its fortune from coal.

But the question for the people of West Virginia must be, will their governor’s friendship with Trump help them?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe new coal jobs have yet to materialise, even with recent suspension of clean air rules.

There have been a few hundred jobs created since 2016, most before Trump’s coronation, but there is no sign of the renaissance he promised.

The US coal industry is in terminal decline, just as Britain’s was 20 years ago.

And just as Britain’s coalfield communities struggled after the pits closed, so West Virginians are finding it hard to prosper in this new climate, where natural gas is cheaper and easier to extract from West Virginia’s hard lands, and hope is in short supply.

As if the state didn’t have enough to contend with, opioid addiction has taken root, fuelled by a national pharmaceutical industry that appears to put profit before people.

A recent report by a congressional committee revealed that, over ten short years, two major drug companies shipped 21 million opiate-based painkillers to two small pharmacies in Williamson, a former mining town with only 3,200 residents. That is 6,500 deadly pills for every man, woman and child.

Little wonder that West Virginia has the highest overdose death rate in the country.

And a report published last month by Senator Manchin shows that the opioid crisis cost the state’s economy nearly $9 billion in 2016, in health care spending, addiction treatment, criminal justice and lost productivity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is hard to reconcile the glossy tourism brochures for West Virginia, packed full of #instaworthy locations and shiny, happy people, with the blank-eyed, broken young people we encountered on the streets of the state capital Charleston and in the aisles of Walmart.

It is the same hopelessness we saw a few weeks ago on the outer edges of Harlem, where young men jacked up on the street, oblivious to all but the contents of their needle.

Fifty years ago, this week, Bobby Kennedy, the younger brother of JFK, was assassinated. He is still fondly remembered in West Virginia as a politician who understood the cruel impact of poverty.

He first came to the Mountain State in 1960 to campaign for his brother, and saw for himself the desperation of rural deprivation.

He took West Virginia to his heart, and returned many times, determined to develop policies that would alleviate the poverty he witnessed here, and across the Appalachian region.

When he was standing for a New York senate seat in 1964, he published a book on poverty, in which he wrote: “As long as there is plenty, poverty is evil ... the problem of poverty is the problem of youth. Whether they ‘hang around’ at the side of a muddy road in West Virginia, or on a street corner in Harlem.” Bobby Kennedy did not live to realise his ambition of ridding America, the richest country in the world, of the evil that is poverty.

Donald Trump is largely silent on inequality, preferring instead to “make America great again” by giving tax breaks to rich people and even richer corporations.

What West Virginia, and Harlem, need now, just as they did 50 years ago, is a political leader with the vision and energy – and, crucially, the support in Congress – to realise Bobby Kennedy’s dream.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEnter stage left, Howard Shultz, the man who gave the world Starbucks, and who grew up in a poor Brooklyn household.

He resigned his role as chairman of the global brand he created earlier this week, and is so far coy about his presidential ambitions.

But he did throw out a big hint, saying: “For some time now I have been deeply concerned about our country, the growing division at home ...”

Could the man who persuaded the world to pay over the odds for a milky coffee to go, be the heir to Bobby Kennedy’s dream of “sweeping down the mightiest walls of oppression”, one person, one neighbourhood at a time?