James Cleverly trip shows Britain is all at sea over China

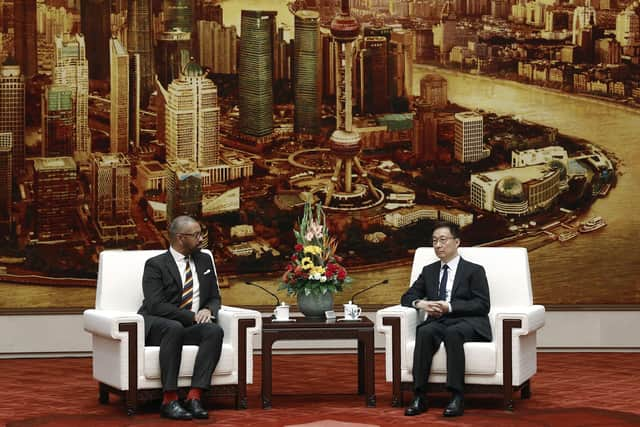

Only James Cleverly knows why he chose to glad hand the Chinese vice president, Han Zheng, in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People earlier this week, but I would propose two possible explanations. Either the foreign secretary is so infatuated with his own modest talents that he believes his presence will have an impact on relations with China, or as Sir Iain Duncan Smith has suggested, the plan is to “appease” a state Mr Cleverly once described as a potential “partner for good.”

His disingenuous defence of his trip - it was, he said, a way to “re-establish lines of communication,” insisting it would not be “credible” to disengage with Beijing - rings hollow. It should be possible for someone in his position to engage in dialogue around vital issues like climate change and international economic stability without recourse to an in-person visit.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome have pointed out that in recent months, China has hosted high-profile guests including US secretary of state, Anthony Blinken. But to suppose that Mr Cleverly belongs in that category is to sorely misjudge modern Britain’s economic and military influence, and the capabilities of its current crop of cabinet ministers.

At the weekend, president Xi Jinping effectively doubled down on his authoritarian government’s treatment of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, insisting that the “Sinofication of Islam should be deepened” to crack down on “illegal religious activities.” On Wednesday meanwhile, the foreign select committee published a report which warned that China’s behaviour was a threat to world security, and urged Britain to take a tougher stance over Beijing’s human rights abuses.

If Mr Cleverly thought it appropriate to proceed with his visit given such developments, or believed that he would be able to broker solutions to such problems, he is, at best, naive. But an even more fundamental mess exposed by the episode is Britain’s inchoate and inconsistent approach to dealing with China. For some time now, a Brexit-inspired myopia has resulted in a muddled approach to foreign affairs by successive Conservative administrations, and the manner in which it deals with the world’s second largest economy is the most ignominious example.

Only last summer, Mr Sunak, then a candidate in the Tory leadership contest, warned that China posed the “biggest long-term threat to Britain,” and vowed to clamp down on its soft power grab by closing dozens of Confucius Institutes. A year on, he has not only U-turned on that promise, but decided that “robust pragmatism” and rapprochement represent the way forward. All without addressing parliament or the public as to how the threats posed by interference and espionage can be effectively repelled.

It may be that Mr Sunak believes the trading relationship with China and the wider Indo-Pacific region must take precedence, and in keeping with a longstanding British tradition, will accept Chinese money with few questions asked. If that is the case, he should spell out how he intends to achieve that by publishing the government's China strategy, a document that has been kept hidden even from senior ministers.

The so-called ‘golden era’ between the two countries has long since passed, but it has been replaced by inconsistency and ambiguity. Unless it makes its stance clear, the government cannot hope to call itself a global leader.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.