Why all public authorities should take note of scathing Daniel Morgan report - John McLellan

Apologies and corrections columns were not just unheard of, but the notion of regular admission of errors went against the principle that any hint of unreliability would damage to the paper’s reputation and readers would flee.

Under the old Press Council, the industry even rejected the notion of a code of conduct, until the 1990 Calcutt Report and the threat of statutory control forced its replacement with the Press Complaints Commission (PCC) the following year to police the new Editors Code of Practice. Before anyone had heard of phone hacking, which eventually destroyed both the News of the World and the PCC, the sharp practices of journalists working with private investigators to “blag” private information was exposed by Operation Motorman in 2003 after the Information Commissioner stumbled across a treasure trove of files kept by a private detective, John Boyall.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt the heart of a tangled web of corrupt police officers and Fleet Street journalists were private investigators, including Boyall, Steve Whittamore, Glenn Mulcaire, and Jonathan Rees. Motorman resulted in Boyall, Whittamore and two retired police officers pleading guilty to misconduct in a public office and they received conditional discharges. When the phone hacking scandal first broke in 2006 Mulcaire was jailed for six months but despite extensive evidence of alleged blagging activities, Rees never faced trial for these offences, although he was jailed for trying to frame a woman in a bitter divorce case.

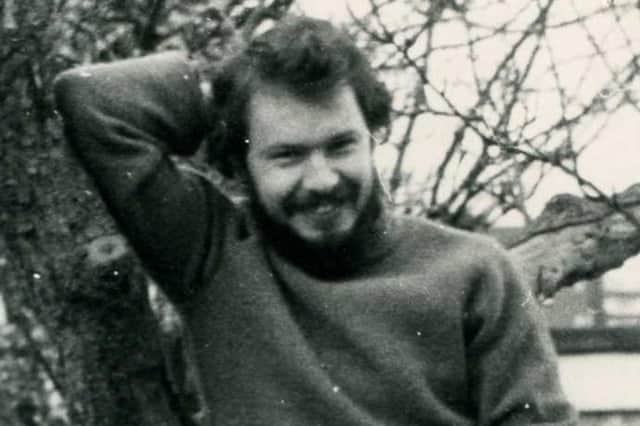

In 2011 Rees was acquitted of the 1987 murder of his business partner Daniel Morgan and the report published this week into the Metropolitan Police’s handling of the investigation into Mr Morgan’s death reads like a Line of Duty script, with a cast of bent coppers, cynical private eyes and grieving relatives and a parade of senior officers up to the present day who, said the report, prioritised the force’s reputation above all else. “In failing to acknowledge its many failings over the 34 years since the murder of Daniel Morgan, the Metropolitan Police’s first objective was to protect itself,” said the report. “In so doing it compounded the suffering and trauma of the family.” It couldn’t be more damning, and as has become her habit in the face of severe criticism Met Commissioner Dame Cressida Dick has refused to resign amidst claims she caused the report’s delay. It’s all over, nothing to see here, move on please.

Except it’s not all over for the restoration of public confidence, but the Met is not alone in giving the highest priority to reputational defence. It would be an exception if it didn’t. To a degree it’s understandable for commercial organisations, like newspaper publishers, to double down in a crisis which threatens revenue and customers, and crisis management is a lucrative specialisation within the burgeoning public relations industry. The irony is that when the crisis specialists arrive, the world knows there’s a problem. News organisations learnt the hard way that being open about failings was better than protracted wrangles, but as well as the imperative to head off the threat of statutory control it was also driven by commercial pressure to settle disputes and avoid needless expense.

But what about public authorities? Police forces, local councils and, yes, the BBC, aren’t under anything like the same commercial pressures and are already subject to statutory controls, but they are repeatedly sucked into damage limitation exercises only to defend reputations. It is perfectly understandable for individuals to fear that exposure of incompetence or criminality could threaten their careers and livelihoods, but public organisations’ first duty is to the public, not the staff. As the Daniel Morgan Report was published there was the latest twist in the long-running Martin Bashir saga, dating back to the BBC reporter’s now infamous 1995 interview with Princess Diana, with the publication of an investigation into how he had been re-hired by the BBC in 2016 and the UK Government warning the Corporation to change its “we know best” culture. That both the BBC and Met are still dealing with issues dating back 26 and 34 years respectively says much about the public bodies’ attitude towards public accountability.

Not a week goes by without some public organisation using spurious excuses to reject Freedom of Information requests purely to save face.

There is the £12m inquiry into the disastrous Edinburgh tram project going back 15 years, which has still not been published because, it is believed, of objections from key witnesses, and Edinburgh Council is currently burning through public money in a complex internal inquiry which includes unresolved issues about complaint handling as long ago as 2002.

When the Defamation Act went through the Scottish Parliament this year, a crucial element was the so-called “Derbyshire Principle”, named after Derbyshire County Council and prevents public authorities from suing for libel, because councils have no reputation to damage in a financial sense which can be compensated. After all, it’s not as if we can take our Council Tax elsewhere. Yet public authorities go to extraordinary lengths to avoid criticism when public embarrassment is an intrinsic part of the system; avoiding it is therefore not in the public interest and logically the Derbyshire Principle should go beyond defamation to all matters of reputation defence.

Here is the key finding of the Daniel Morgan report: “The lack of leadership, the reluctance to confront serious issues and the refusal to be publicly and internally candid about failings and deficiencies within the organisation, in this case and others, engenders distrust among the community.”

All public authorities should take note and even if it’s an old cliché, sunlight really is the strongest disinfectant

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.