What the 1930s US plan to invade Canada says about Donald Trump – Alastair Stewart

Early on in his presidency, some gave Donald Trump the benefit of the doubt and presumed he was practising Richard Nixon’s ‘madman theory’. President Nixon and Henry Kissinger believed if they could make the Viet Cong think he was unhinged enough to press the nuclear button, they’d negotiate favourably.

Four years later, that’s an insult to Nixon. Not only has Trump threatened the UK with a trade war, but he’s also now cut funding to the World Health Organisation. With friends like these, who needs enemies? And yet he is hardly the first president to be imperial – just one of the handful.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the final decade of the 19th century and into the 20th, the United States had fought in the American Indian Wars, the Mexican Border War, the Banana Wars, sent forces into the Boxer Rebellion, the Russian Revolution and ‘the war to end all wars’. Territories gained from the Spanish-American War of 1898 (including Cuba, Guam, and Puerto Rico) made the US an empire by definition.

It was President Theodore Roosevelt, not Woodrow Wilson and his liberal internationalism in World War One, who first wanted to show off some Pax Americana muscle. The US Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’ tour was about “speaking softly and carrying a big stick” to the world between 1907-09.

By the 1920s, the US was anticipating a punch-up with anyone from Japan and Russia to its chief rival for global hegemony, the British Empire.

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1921 was the first arms control conference in history. Although meant to stop a costly and dangerous arms race, it actually left the British in a superior naval position. The 1927 Geneva Naval Conference was likewise intended to reduce naval construction and international rivalry. No definitive agreement was secured, and Britain, Japan, the US, and France all continued to feel threatened by one another.

After World War One, Britain avoided a repeat of the arms race with Germany before 1914, but power begets fear. The empire’s massive commercial interests made a run-in with the US seem inevitable.

And so between 1929 and 1933, the Herbert Hoover administration produced several colour-coded scenarios for war against the powers of the day. They were unsentimental and centred on who could threaten the US.

‘War Plan Red’ envisioned a scenario in which the UK, with or through Canada, attacked. If the British could torch the White House in 1814, was a new war really out of the question?

Britain and America endured a contentious century of border disputes over Canada. The Aroostook War (1838–39) and the Bering Sea Arbitration of 1893 sit alongside a pantheon of other conflicts, not least of all the War of 1812. And let’s not forget the Pig War of 1859 when it nearly came to blows or when a British invasion force almost declared war after the Trent Affair of 1861.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGunboat diplomacy was nothing new for the British Empire. The country might have been indebted to the US for its First World War support, but it still had a massive navy and a track record of protecting its imperial interests.

Global arms agreements didn’t negate the reality of British preeminence. Since the Naval Defence Act (1889), Britain had a ‘two-power’ standard requiring her fleet to be larger than the next two powers combined. Britain’s imperial ambition was alive and well.

Although American rhetoric might have found power politics repugnant in the Republic’s early years, it became very good at it after ‘Manifest Destiny’ and ‘American exceptionalism’ touched coast to coast. The young country was no longer shy to think of its global interests.

With this context in mind, the War Plan Red proposed preemptively attacking Canadian forces before Britain could send aid to bases, ports and airfields. Halifax, Nova Scotia, was a prime target to blockade support with the real questions raised of whether the entire country could be taken.

The Royal Navy never prepared a formal plan for war with the United States during the first half of the 20th century, perhaps a sign of its acceptance rather than overconfidence. Britain knew Canada would be impossible to defend. A full-scale invasion of America in retaliation was unlikely; a blockade would be too slow and ineffective and the loss of Canada not detrimental to the survival of the empire.

The War Plan Red documents were declassified in 1974. While causing a minor political debate, they are a remarkable insight into geopolitical thinking of the day. They sit among the most extraordinary ‘what-ifs’, right beside Winston Churchill’s drunken, outraged plans to forcibly take back eastern Europe from Stalin. ‘Operation Unthinkable’ was only made public in 1988.

If the plans tell us anything new, it’s that Donald Trump is not the first, or the last, US president straddling the world with boorishness. From its inception, America always struggled with being an ‘Empire of Liberty’ – as Thomas Jefferson called it – while not “entangl[ing] the United States in foreign alliances”, which George Washington warned against.

Michael Doyle’s argument that democracies are less likely to go to war with one another is just as half-blind to history as Francis Fukuyama claiming American democracy was the “end of history”. Henry Kissinger receiving the Nobel Peace Prize was truly what James Hogg might have called the ‘Confessions of a Justified Sinner’. Trump operates in the latest, most brazen paradigm of self-delusion.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf there’s a certain facetiousness, it’s because no other country in the world has so utterly failed its empty tonnage of rhetoric and produced such hypocrisy. Trump is a symptom, not a cause.

Wilson and Roosevelt, both so different, each wanted to achieve a global empire in the 20th century under different auspices – and dared to call it freedom. Trump is no different; he’s just armed with Twitter, not the pulpit.

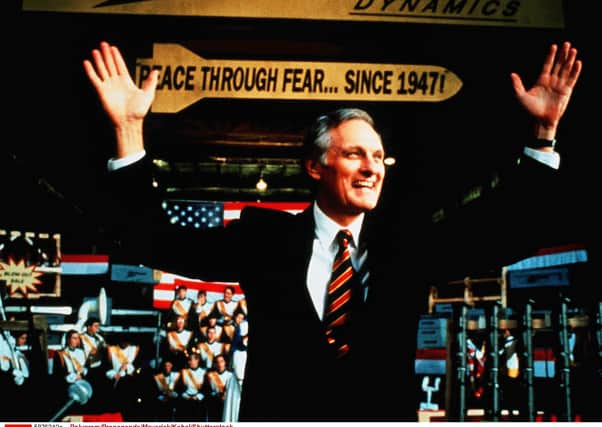

Harold Macmillan thought Britain could be like the Ancient Greeks to the Roman Empire. Instead, we could have ended up as ‘Canadian Bacon’.

Alastair Stewart is a public affairs consultant with Orbit Communications. He regularly writes about politics and history with a particular interest in the life of Sir Winston Churchill. Read more from Alastair at www.agjstewart.com and follow him on Twitter @agjstewart

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.