What is the point of public inquiries? - John Sturrock

The revelation that the trams inquiry is now as costly as the investigation into the Iraq war, and that eight years have elapsed since a “swift and thorough” process was commissioned, has raised concerns about the purpose and efficacy of the inquiry process. Lord Hardie, who leads the inquiry, has said it will take “as long as is necessary”.

Such inquiries consume large amounts of public funds. And yet, their independence is critical. The whole point is to be able to shine a light on events which have been unsatisfactory, without government or any other interested party inappropriately influencing the outcome. So far so good.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, there may be questions to be asked. What, if any, accountability should there be for this expenditure of taxpayers’ money? Should there be an independent oversight body to scrutinise the conduct of an inquiry and assess value for money? Would that simply become another cost, or could such a body set appropriate benchmarks against which performance could be measured?

What about duration? Should an inquiry be allowed to take “as long as is necessary”, however long that may turn out to be? How is “necessity” to be determined? And by whom? Does there come a point when the trade-off between duration and useful outcome requires examination? What is the purpose of an inquiry if it takes so long that its recommendations are not useful in determining policy and decision-making in the future? After all, we are told that 84% of the tram extension has already been laid.

This leads to more questions. Is such an inquiry designed to find fault and allocate blame for events which occurred? Or is it to discover what went wrong and why – and recommend different approaches in the future? A mixture of both? Is there danger that undue emphasis on the former may create an adversarial environment following the litigation model, where everyone who may be held responsible is represented by lawyers whose primary function is to absolve their client from blame? Could this lead to less openness and more defensiveness, making it less likely the real facts will be revealed? Is this one reason that inquiries can take so long?

Is it necessary to carry out a full forensic investigation of every document? We are told the trams inquiry’s “evidential database contains over three million documents that have to be carefully considered, which is an extensive, but vital task.” It may be a vital task on one view, but might that depend on the approach? Is there another sufficiently satisfactory way to get to a useful outcome without such expenditure of time and money?

It is almost always the case that a senior judge, usually but not always nearing retirement, is appointed as chair. There are good reasons for this of course: independence, experience, authority, ability to absorb and analyse detail. But what other skills might be needed for these extraordinary exercises? Subject-matter expertise? Ability to cut through detail and identify key points? Delegation? Management of time? What about facilitation or inquisitorial skills, the ability to draw out the real underlying issues, key differences and common ground quickly, in a non-confrontational environment? Should the pool for possible chairs be expanded? Or, at least, might there be a case for specialists, with differing skills, to co-chair?

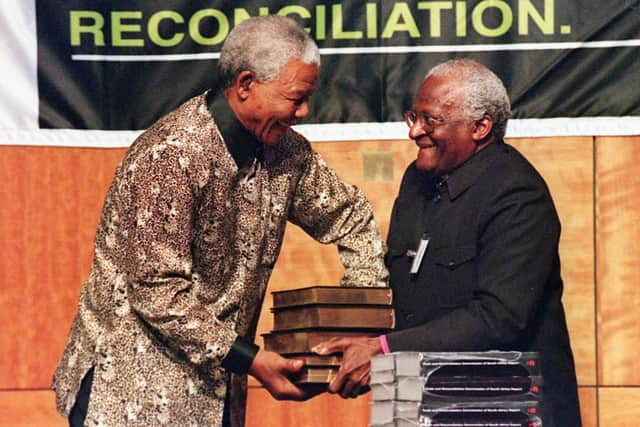

What other options are there? Radically, could an inquiry be designed in the way that the great Desmond Tutu, in a different situation of course, handled the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa? How do we balance the past with the future – and retribution with restoration? This might be particularly relevant in the forthcoming Covid Inquiry.

At the end of the day, in a matter of legitimate public concern, this seems to be about identifying the appropriate purpose, method, personnel, expenditure, expected outcome and timescale for such projects. Perhaps the moment has come for a serious rethink.

John Sturrock KC, conducted a review into bullying in NHS Highland in 2019.