Westminster and Holyrood need to end the macho, partisan nonsense and work together – Ian Dunt

Long-held assumptions about SNP dominance or the behaviour of Downing Street are no longer reliable. Things may be about to change drastically. And thank God for that. The Union is in a disastrous state. The reason for that is not about the Barnett formula or any of that. It's about tribal antipathy. A practical two-way working relationship has been replaced with partisan zero-sum political conflict.

It's in the SNP's interest to frame itself in opposition to Westminster, so all achievements north of the Border are treated as a triumph of the devolved government and all failures are pinned on London. But that hands-over-the-ears process has been replicated south of the Border too. Powers which should rightfully have belonged to Scotland have been captured and zealously guarded, rather than shared. A pragmatic partnership was jettisoned in favour of no-holds-barred political warfare.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTake the 2020 United Kingdom Internal Market Act. It provoked outrage because of clauses allowing ministers to break international law, but in fact they were a smokescreen to conceal the true purpose of the bill: a complex series of moves which put the power to pass laws on goods and trade in post-Brexit Britain in the hands of ministers in Westminster rather than the devolved assemblies. As Nicola McEwen, professor of territorial politics at Edinburgh University, said, it represented a “significant recentralisation of power”.

This has been the default model for Westminster's treatment of the Scottish Government since the Brexit vote: aggression, constitutional sleight-of-hand and oneupmanship. And it is the default model for how Westminster is treated in return by the SNP, as a jailor and a tyrant rather than a working partner. The Conservative government went out of its way to confirm that image, but the SNP would have promoted it regardless.

The tragedy at the heart of this broken marriage is that Westminster and Holyrood have plenty to learn from each other. Take one slightly odd example: the committee system. This is the point in the passage of a new law when a group of politicians sit down and take a forensic look at it so they can address its deficiencies. No one ever really talks about it. It's considered the highest form of political nerdery to even mention it. But it's the difference between parliaments that make good law and parliaments that make bad law.

Westminster's committee arrangements are basically insane. They're called public bill committees. These are ad-hoc, so they never sit for long enough to develop specialist expertise. They have no in-depth knowledge of the subject the legislation covers and often don't even have a superficial understanding of it. They're composed according to the parties' seats in the Commons, so the big stonking majority handed to the government by the first-past-the-post system allows them to trample over any possible opposition amendments. MPs vote for what they're told to vote for and vote against what they're told to vote against. They are not truly legislators. They are machines, working to the demands of the leadership. The idea that the system could be used to actually improve legislation is laughable.

Holyrood looked further afield when it set up its own committees, at countries like the US and Germany, where more effective systems are in operation. In Scotland, the committees sit permanently, develop strong expertise and generally at least try to find consensus. Because of the different electoral system, the Scottish Government is deprived of the large majority enjoyed in London and has to therefore give way more frequently.

The result is that Scottish legislation is generally of a better quality than Westminster legislation. It is challenged more effectively on the basis of specialist knowledge and it goes through a scrutiny process where amendments are possible rather than simply batted away.

Look at the Hate Crime and Public Order Bill from 2021, for instance. It was a sloppy and dangerous bit of legislation which sought to consolidate hate crime laws but in doing so raised all sorts of implications for free speech. A series of amendments then vastly improved it. One expressly exempted “expressions of antipathy, dislike, ridicule or insult towards… religion” from prosecution. Another required the courts to pay “particular regard” to the right to freedom of expression in the European Convention on Human Rights. Critics had the power and the forum to put down changes which had a viable chance of being passed.

Compare it to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill in Westminster, which criminalised “inconvenience” and “annoyance” as well as letting police close down any protest which might cause “serious disruption to the activities of an organisation”. That alone was a massive infringement of free speech. But worst of all, it gave the Home Secretary the power to define many of its key terms in future. No judge, no jury, no parliament – just the Home Secretary unilaterally deciding what terms meant and who would be criminalised by them. The Bill went through with all its defects in place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere are lessons to be learned here, going both ways. We can have a system of experimentation, where we try something in one part of the UK, then replicate it in another if it works – a genuinely vibrant and dynamic constitutional arrangement where differences become advantages.

But for that to happen, we need an end to the macho tit-for-tat partisan nonsense of the last few years and commit to a pragmatic working relationship. The Union is about to enter a period of flux. We should demand that the new status quo is more rational and mutually beneficial than the last one.

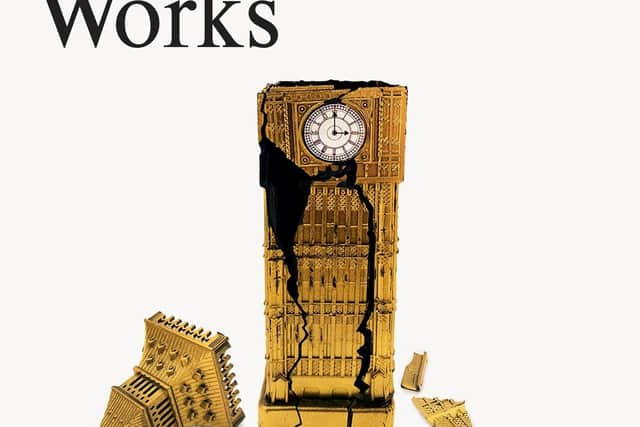

How Westminster Works… and Why it Doesn’t by Ian Dunt is published on April 13. Ian Dunt will be at Toppings St Andrews on April 24, Toppings Edinburgh on April 25, and Glasgow’s Aye Write! Festival on May 27.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.