We start 2022 in the same spirit we started 2021: battered but hopeful - Dani Garavelli

It started off with Scotland back in lockdown. Yet, though we were in level four - confined to our local authority areas, allowed to meet up only outdoors with one other household - the tang of spring, and the prospect of renewal, was in the air.

In the US, the storming of the Capitol - terrifying as it was - turned out to be, not a serious threat to democracy but the death throes of Donald Trump’s presidency. Within days, he had been permanently suspended from Twitter. After his successor’s inauguration, the man whose incoherent, yet dangerous pronouncements had cast a shadow on the world, faded from public consciousness.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDemocrat Joe Biden might not have possessed the energy and radicalism some hoped for, but he did immediately rejoin the Paris Agreement on climate change which Trump had abandoned. When poet Amanda Gorman recited The Hill We Climb at his swearing-in, the message of perseverance - while rooted in racial oppression - seemed to capture the mood. “The new dawn blooms as we free it,” she said. “For there is light if only we’re brave enough to see it.”

And there was light. By then, three vaccines - Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Moderna - had all been approved for use in the UK, and the national roll-out had started, with care home residents, care workers, the over-70s and those with underlying conditions prioritised, and a series of mass vaccination centres established.

Though thwarted by the emergence of new variants - first Delta and then Omicron - the programme was impressive. The UK and Scottish governments hit their target of offering the vaccine to all adults by July 2021 and responded to fresh waves by redoubling their efforts and offering boosters. Despite the rise of the anti-vaxxers, take-up has been high. By 13 December, 89.1 per cent of the population aged 12 and over had received their first vaccine, 81.3 per cent had received their second and 40.2 per cent had had a booster or third dose. Though the total UK death toll now stands at 150,000 - and the vaccines have not prevented transmission - they have reduced the severity of the symptoms for most.

Of course, the success of the UK’s vaccine programme has come at the expense of other countries. As with everything, the global north has taken more than its fair share, leaving countries in the global south, particularly Africa, wanting. In the poorest countries, just 3 per cent of the population is fully vaccinated. This situation is not only morally repugnant but epidemiologically and politically short-sighted. The unchecked spread of Covid-19 in unvaccinated populations is what allows mutations, such as Omicron, to take place. A global pandemic cannot end without global vaccination.

Dreams of a return to normality - or at least of establishing a “new normal” - have waxed and waned throughout the year, as restrictions have been relaxed, then reinforced, in line with the perceived threat. The post-Christmas “circuit breaker” lingered on, but in Scotland, there was an outbreak of joy in April, as Nicola Sturgeon announced a move to level three. This meant we could, at last, cross local authority boundaries and meet up to six households outdoors. Children could go back to school.

Gradually, everything loosened up. Cinemas reopened. Coffee houses and bars filled up. Football stadiums welcomed fans back in. The Edinburgh festivals and Fringe returned, albeit in smaller form.

In late August, the nightclubs also reopened. And gigs - cancelled and rescheduled and cancelled again - finally took place. Photographs of the Glasgow Barrowland iconic sign started appearing on Twitter feeds as those starved of live music marked their first time back on hallowed ground.

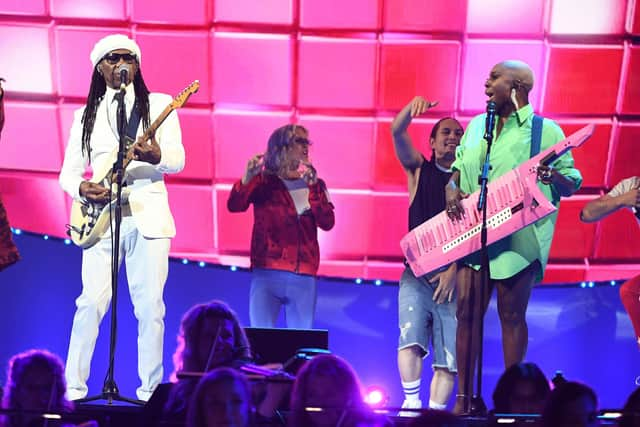

My favourite night was dancing in the rain to Nile Rodgers at the Playground Festival in Rouken Glen Park; but everyone will have their own memories of happiness snatched from the gloom.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOf course, with the opening up came fresh anxieties. The wild scenes of Tartan Army partying in Leicester Square during the Euros in June were disconcerting and followed, unsurprisingly, by a spike in infections. Boris Johnson’s so-called Freedom Day, a month later - when laws requiring masks to be worn in shops and other indoor settings lapsed - seemed cavalier and coincided with a period of increased track and trace pinging and self-isolation.

In Scotland, masks were still required in shops, pubs/cafes and public transport, but enforcing the rules became more difficult, as anyone who travelled to or from England by train will know. They weren’t worn much at gigs, either, making the experience more fraught than it needed to be. And the collection of information for test and protect started to slide. Still, no-one making their tentative journey back into the world in early autumn could have foreseen the invasion of Omicron. Or that we would be facing another partial lockdown by Christmas.

High hopes were dashed elsewhere, too. The Biden presidency has fallen short of already-tempered expectations, with the removal of troops from Afghanistan, a stain on both the US and the UK. The Taliban began its offensive within days of the initial withdrawal in May and by August Kabul had fallen.

The chaotic evacuation operation should be a source of eternal shame. Whistle-blower Raphael Marshall, a former diplomat, told how thousands of emails from desperate Afghan nationals went unread as Foreign Office officials worked from home and watched the clock. He confirmed rescue dogs from the charity Nowzad were flown to the UK at the direct expense of people.

The conviction of white US police officer Derek Chauvin of the murder of George Floyd in June was a huge relief (given past exonerations in similar cases) and suggested the Black Lives Matter movement might be having an impact. But elsewhere, racism continued to flourish. When, under the management of Gareth Southgate, England players took the knee before Euro matches, they found themselves booed by some of their own fans. Then the three black players who missed penalties in the final against Italy were subjected to an onslaught of social media abuse.

Home Secretary Priti Patel continued her campaign against migrants, with her Nationality and Borders Bill. Already passed by the House of Commons, it would make it illegal to help asylum seekers enter the UK, empower Border Patrol to turn back boats full of refugees and give the government the right to strip people of their British citizenship without warning. Twenty seven migrants drowned in the channel in November. Instead of forcing a U-turn, this tragedy prompted a blame game between the UK and French governments. Patel carried on regardless.

It was a difficult year for women too (what year isn’t?). The election of Kamala Harris as the US’s first female and BAME VP augured well. But the scale of the misogyny that pervades our institutions was exposed by the murder of Sarah Everard in March. Everard was abducted, raped and murdered by serving Metropolitan police office Wayne Couzens whose previous behaviour had already raised concerns. Couzens exploited his position and the pandemic, arresting and handcuffing Everard for a supposed breach of Covid restrictions.

If the murder was horrific, so too was the response of the Met and its Commissioner Cressida Dick. At a vigil held for Everard at Clapham Common, police officers manhandled and arrested female protesters. In one of the most iconic images of the year, one of those women, Patsy Stevenson, was photographed pinned to the ground but looking defiantly at the camera.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was lots of victim-blaming. Yorkshire Police and Crime Commissioner Philip Allott was forced to resign after suggesting Everard was at fault for not being better acquainted with the law. Meanwhile, two other Met officers were suspended for taking photographs of the bodies of sisters Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry murdered last year. The officers were later jailed. Dick has not resigned.

In Scotland, a campaign to pardon 4,000 people, mostly women, convicted of witchcraft in the 16th to 18th centuries has been gaining momentum. Sturgeon has now backed a private members’ bill and an apology is expected on International Women's Day in March. You do not have to look much further than Scotland Yard to understand the contemporary relevance of a move which seeks redress for persecuted women.

Some positives did emerge from the pandemic. One was the plethora of top-notch TV shows for us all to watch from the confines of our living rooms. Shows like It’s a Sin, The Mare of Easttown, Succession and the second season of Neil Forsyth’s excellent Guilt became communal experiences shared through social media. Last year also brought the first big pandemic dramas. Together, starring James McAvoy and Sharon Horgan, explored the impact of lockdown on an already fraught marriage, while Help, starring Jodie Comer and Stephen Graham, looked at the plight of care workers.

Musical highlights included Scottish band Mogwai reaching Number One in the album charts for the first time in their 25-year career with As The Love Continues. Then - just when we needed them most - everybody’s favourite Swedish export, Abba, turned up to transport us back to the days of spangles and platform boots, releasing two songs: I Still Have Faith in You and Don’t Shut Me to mass excitement.

Sport also produced some unforgettable moments. Under manager Steve Clarke, the Scotland men’s team had regained its form and qualified for the Euros - its first international tournament for more than 20 years. As the squad prepared to take on the Czech Republic, England and Croatia, its new unofficial anthem, Baccara’s Yes Sir, I can Boogie, was on the lips of every fan. Scotland didn’t get past the first group stage, but a nil-nil draw with England was celebrated like a victory; and at least we’d been there.

Later the same month, Andy Murray returned to Wimbledon for the first time since 2017. His flair and stoicism were once again on display as he beat Nikoloz Basilashvili, then Oscar Otte before losing to Denis Shapovalov in the third round. It was a joy to see him back on court. But it was an even bigger joy to see Emma Raducanu triumph at the US Open. She is the first British woman to win a Grand Slam tournament since 1977.

Raducanu's victory was a vindication of her resilience as she had been criticised by (mostly male) commentators when she had pulled out of Wimbledon with breathing difficulties. Piers Morgan, who had carped about her inability to handle pressure, looked particularly stupid.

Another woman praised for her stoicism was the Queen. She was photographed sitting alone at the funeral of Prince Philip, her husband of 73 years, in compliance with the Covid restrictions. She looked so statesmanlike compared to those Conservatives who partied while the rest of the country made sacrifices. Her dignity also stood in stark contrast to her son Prince Andrew whose reputation continued to be tarnished by his association with Ghislaine Maxwell. Maxwell is now on trial accused of preying on and grooming young girls for convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein to abuse.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn October, the Met dropped its investigation into claims made by Virginia Giuffre that Prince Andrew had sex with her when she was 17 after she was trafficked by Epstein. She filed a civil case which is still ongoing. Guiffre has been described as Banquo’s ghost at Maxwell’s trial - mentioned more than 38 times but not called as a witness.

Allegations of sexual impropriety were also at the heart of Scotland’s biggest political drama: the parliamentary inquiry into how the initial claims against Alex Salmond were handled by the Scottish government. No-one came out of it well. All parties appeared uncooperative while the women at the centre of it were pawns in a wider political game. Salmond had been acquitted of all charges at his trial. But there was never any evidence to back his claim of an orchestrated plot to bring him down. For a while, it looked like Sturgeon might be forced to resign for breaching the ministerial code. But she was cleared of this by a separate inquiry - led by James Hamilton - and she prepared to lead her party into the Holyrood election.

No sooner had the First Minister breathed a sigh of relief than Salmond was forming a new party to stand against her. He exploited divisions in the SNP, and some councillors, MPs and former MSPs defected. In the end, Alba failed to register more than two percent of the vote share in any of the eight regional lists or to return a single MSP. The SNP returned 64 MSPs, just short of an overall majority and went on to forge their first formal alliance with the Scottish Greens. This was supposed to allow them to present a united front to Johnson in a demand for IndyRef2. But the need to firefight the pandemic means a fresh plebiscite has once again been placed on the backburner.

Having the Scottish Greens on board also lent the SNP credibility in the run-up to COP26, the international climate change conference held in Glasgow in November. Throughout the year, the planet was gripped by extreme weather events: from the deep freeze in Texas to the cyclone in Indonesia to the wildfires in Greece, all illustrating the need for dramatic action. COP26 delivered the Glasgow Climate Pact: the first ever deal to explicitly plan to reduce coal, the worst fossil fuel for greenhouse gases. However the wording of the pact was watered down at the last minute, and sceptics believe the pledges did not go far enough to limit temperature rise to 1.5C as per the Paris Agreement.

This was a disappointment. But climate change protesters at COP26 also campaigned against future drilling at Cambo, an oilfield west of Shetland. They claimed new oil and gas developments were incompatible with reaching zero emissions. Earlier this month, Shell pulled out, halting development work.

When senior aide Allegra Stratton resigned earlier this month, in the midst of the government’s ongoing Christmas party scandal, she asked for her work as COP26 spokesperson for Johnson to be recognised. But she knows she will be forever linked in the public consciousness with the lies and hypocrisy of a party which ignored the rules it imposed on the rest of us.

The footage of her snickering during a practice press conference, where she was asked about a Christmas do for staff at Number 10, summed up the contempt in which the Conservatives appear to hold ordinary people.

In fact, resentment towards the Johnson government had begun to build a few weeks earlier when the Prime Minister tried to rip up the parliamentary standards regime. He wanted to protect MP Owen Paterson from a 30-day suspension for an “egregious” breach of the lobby rules.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was a backlash, and Johnson was forced into a U-turn. Paterson resigned which led to the humiliating North Shropshire by-election in which a Tory majority of almost 23,000 was overturned by Liberal Democrat Helen Morgan.

All this has been unfolding against the back-drop of the growing Omicron crisis. As the number of cases of the new variant soared - bringing concerns the NHS would be overwhelmed - Johnson and the leaders of the devolved governments were forced to rethink existing restrictions.

With the right-wing libertarians in his party opposed to another lockdown, Johnson had to rely on Labour to get his Plan B - which involved the reintroduction of masks in some indoor settings - through parliament. He shelved a decision on more restrictions for the New Year leading to claims of cabinet infighting. In Scotland, Sturgeon reintroduced stricter rules for shops and hospitality and imposed a limit on numbers for indoor and outdoor events, while urging the public to meet with no more than two other households and take regular lateral flow tests.

With the UK government refusing to act, and the Scottish government lacking the power to borrow, Sturgeon has been able to find just £100m to help businesses deal with the sudden cancellations - a sum they say falls far short of what is required.

We are all exhausted by 21 months of pandemic; our resources are depleted. The country which - last January - thought it was heading for the light is plunged into the dark again. And yet, all is not lost. Despite this depressing step backwards, we are in a better place than we were last December. Most of us are doubly vaccinated, with more people receiving their boosters every day. And those of us who are vaccinated are less likely to become seriously ill.

For the first time since he was elected leader, it looks like Johnson’s jacket might be on a shoogly peg. More stories of illicit socialising are breaking. The photograph of him, Carrie and others drinking wine in the garden of No 10 in May 2020 is a stake in the heart of all those who made painful sacrifices: those whose loved ones died alone; those forced to grieve without the comfort of a hug. The anger is palpable. Perhaps, to paraphrase Johnson's hero Winston Churchill, if this is not the beginning of the end, then it is at least the end of the beginning.

In the last few days, there have been more positive stories, too. Two studies, including one by experts at Edinburgh University, say Omicron is 40 per cent less severe than Delta, and so less likely to cause hospitalisation; the US Army says it has created the first vaccine effective against all Covid and SARS variants, while the US Food and Drug Administration has approved an anti-Covid pill which could treat the worst symptoms of the virus.

We have been here before. Experience tells us not to place too much faith in such developments. But what can we do but cling on to the small comforts we are offered? And so we may start 2022 in the same spirit as we started 2021: battered but hopeful.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.