We should ask more questions of our leaders – who must take responsibility for their answers - Brian Monteith

I cannot deny I have enjoyed some good moments myself; my mother’s ninetieth birthday, a son becoming an art teacher, another excelling in the City, a grand-child starting school and two Cup finals at Hampden to look forward to…

Nevertheless, there are always balancing disappointments; losing two friends in Vivian Linacre and Keith Harding, losing two cup finals at Hampden, and the pandemic restrictions making life far tougher economically than before. These were, however, all personal experiences – in looking back to 2021 I see the political balance sheet as firmly in the red and far more alarming for Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

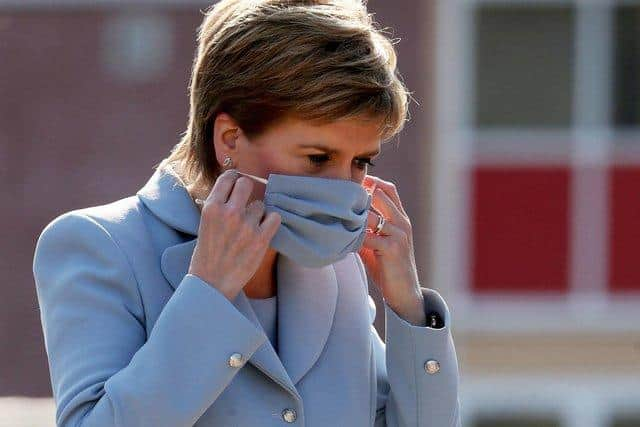

Hide AdThankfully, the SNP was denied a majority in the Holyrood elections, but Nicola Sturgeon continues in power, thanks in no small part to the opposition parties resorting to fighting themselves for second spot rather than challenging the SNP’s record. If the opposition separately cannot defeat an administration that has presided so catastrophically in the decline of public services – its chief if not only responsibility – then what does it take for them to recognise that finding a way to work together should at least be tried?

In the final days of 2021 former Conservative MSP Professor Adam Tomkins called for such a change in approach, advocated before in this column, but is anyone listening that can make such a change become real?

All it takes is to identify what really matters to ordinary people by asking some simple questions. What is more important to Scots in the coming years?

Improving our schools so that the levels of child literacy and numeracy recover and become gold standards once again – or focussing on breaking up Britain?

Restoring our chronically ill NHS – now faced with a waiting list backlog that will take a decade to clear – or focussing on leaving the country that founded it?

Delivering real power to communities by restoring the budgets of local councils that are far closer to the people – or focussing on centralising power in a Holyrood parliament that might as well be on Comet Dibiasky than at the foot of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile?

Reviving a Scottish economy by making it more affordable for people and businesses to flourish and prosper – or, in the name of ‘independence’, raising taxes so much that revenues actually fall – making Scotland even more financially dependent on England than when the SNP came to power.

Those are just four areas where common cause and common solutions could be found that would still leave a great deal of room for adult disagreement – not least that the parties would naturally differ in policies they advocate at Westminster, where the responsibilities are for the whole UK.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe lesson and example of politicians working together for the common good rather than objecting to the ideas of opponents for no more than the sake of it – a tribalism that is pulling Scotland backwards – would surely be of value in seeking to heal the deep wounds that the unrequited attempt at Scottish secession has generated.

Margaret Thatcher is dead. Anyone under 53 could not have voted for her in her last election of 1987, thirty-five years ago. Anyone under 35 could not have voted for Tony Blair in his last election of 2005, coming up for seventeen years ago. It is absurd to be fighting the elections of the third decade of the twenty-first century over the battles of 1979, 83, 87 and all the way through to 1997, 2001 and 2005.

We now have devolution (made possible delivered by Blair) – if it is to work then it requires co-operation between parties – as that is the way it is designed. It is long overdue that the Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties recognised and admitted this to the electorate. The SNP certainly won’t do it for them as it is their division that makes the SNP rule possible.

If they cannot make devolution work then there really are only two alternatives – abolishing Holyrood and giving more power to the local authorities, or settling on a Scottish secession from the UK that must bring a great deal of economic and social pain for at least thirty years before the necessary changes to make it work might be realised.

Yet ‘independence’ is nowhere near coming. The nationalists are philosophically a spent force. They preside over a public collapse in confidence in our education; the safety and capacity of the health service is beyond breaking point; basic transport across Scotland on road, rail and sea has gone backwards; the justice system has been cut back while faux-embassies are expanded – and yet the SNP is allowed to get away with it. Why?

It is simple, the public is encouraged to vote tribally and emotionally by politicians of all parties blaming others in London rather than taking responsibility themselves.

New Year is a time for resolutions – by recognising and accepting our own past failings and resolving to be better we try to become better people. It is high time we did the same for Scotland.

If we are to have a better 2022 – and beyond – our collective New Year’s resolution must be to ask more questions of our Scottish politicians, both those in government and opposition, and demand they take responsibility for the answers. Only then might we actually make devolution work – or face up to the fact our political parties are of no use in a devolved Scotland.

Brian Monteith is editor of ThinkScotland.org and a former member of the Scottish and European Parliaments.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.