We must learn to live with the inconsistencies of lockdown - Dani Garavelli

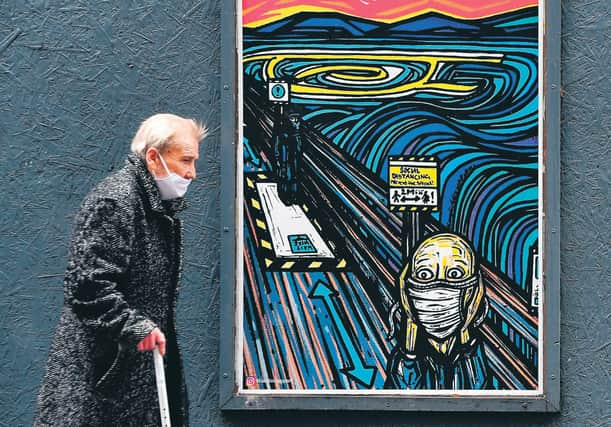

For a while now, this has felt like a two-tier pandemic. For some, life has returned to near normal – school, shopping, foreign holidays, nights at the pub. But for others, the world continues to be a difficult and scary place, dominated by fear of possible infection from every fleeting personal encounter. It is easy to see how the latter group might come to resent the former group, even when they are abiding by the rules; but particularly when they are not.

There has been much talk of young people having house parties and – though it’s probably over-stated – it’s not all a media confection. The notorious 300-strong rave in Midlothian was a commercial event rather than an informal social function. But if the Scottish government felt it necessary to grant fresh powers to the police to break up gatherings of more than 15, we can assume there was a problem.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSo, when the First Minister revealed that – unlike in Aberdeen, where it was focused on the hospitality industry – the latest local lockdown would involve a ban on two households meeting under the same domestic roof of course it felt as if those who had been obeying the rules were being punished for the sins of others. As if a crackdown on safe encounters between close friends and family was the price being paid for the failure to control the wayward behaviour of a minority.

The fact pubs and restaurants were to remain open – so rule-breakers could party on – added insult to injury, fuelling suspicions the economy was being prioritised over the well-being of the old and isolated. “How come you can get blitzed in the pub on Saturday night, but you can’t have your granny over for Sunday dinner?” was the question on many lips, while cynics muttered: “Where there’s a till, there’s a way.”

Sturgeon tried hard to set the record straight. She said data – gathered through test and protect – showed spread in and between households was driving transmission in these local authority areas. Thus the restriction on household gatherings – where social distancing is more difficult – was the most sensible option.

She went on to set out why, counterintuitively, meeting, even in small groups in a house – where crockery might be shared and hugs exchanged – could be more risky than meeting in a pub or restaurant complying with the current pandemic regulations. Denying the partial lockdown was aimed solely at house parties, she said: “There may be an element of that but it is also about family transmission in smaller household gatherings.”

The First Minister’s words provided a degree of reassurance; but not complete clarity. Perhaps the pandemic has made such clarity unrealistic. Everywhere we look there are apparent inconsistencies. What was the point of banning care home visits when residents, who had tested positive, were being returned from hospital? Why can children mingle without social distancing, at school, but not with social distancing in each other’s homes? Why do those returning from Greece – where the infection rate is 14 per 100,000 – to West Dunbartonshire – where the infection rate is 32 per 100,000 – have to quarantine?

The politicians insist they are following the science – as they ought to – but Covid-19 is new and complex, and the science is constantly shifting. In the beginning, there was no evidence of human to human transmission, and then there was. Those who were Covid-19-positive, but asymptomatic could not pass it on, and then they could. Masks were ineffective, and then they were compulsory. This is not a criticism. It’s the way science works, but it does mean there will always be a niggling doubt about whether this week’s guidance is definitive.

Nor does everyone interpret the same science in the same way. Last week, British holidaymakers in Greece faced different quarantine rules depending on whether they lived in Scotland, England or Wales. This is not confusing in the sense that the three countries have taken different approaches on devolved issues for many years now. And presumably those holidaymakers know which country they are returning to. But the fact three governments can look at the same science and reach different conclusions is a reminder that – however hard politicians apply themselves – some of their decisions will be if not arbitrary, then at least arguable.

While I have no reason to doubt Sturgeon’s words, what we are told at the briefings does not always tally with our own experiences. For example, in East Renfrewshire at least one restaurant has closed as a result of a Covid-19 outbreak, while several others have experienced individual cases. This does not mean that those who want to close restaurants are right and the First Minister is wrong. But it does mean there may be some cognitive dissonance to overcome before the wisdom of her rulings will be accepted.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFurthermore, the empirical evidence on testing suggests demand exceeds capacity. Since the schools went back – prompting an inevitable upsurge in colds – the phone-lines have been jammed with the parents of children who have been told they can’t return to the classroom until they have been assessed for Covid-19. Some of those looking for tests have been advised to drive hundreds of miles to get them. Some of those who have had tests are waiting up to a week for results. All this has a knock-on effect . It means parents cannot work; it means elderly people have to fend without their carers, but it also means faith in the system is undermined.

Add to this – fresh from the US Culture wars – a small but vociferous band of mask-refusers, and a general weariness with the ups and downs of pandemic life, and no wonder people appear less eager to comply with lockdown this time round.

But comply we must, unless we want to end up back where we started. Already, the R number is back above 1 - possibly as high as 1.4. The number of cases is rising and, unless we act, more deaths will follow.

So we must try to get our head round some of the apparent contradictions; to appreciate that the decisions being taken are not based on a straightforward comparison of risk factors, but on complex risk/benefit assessment. And that sometimes a risk being taken in one crucial setting, such as schools, may have to be offset by a curtailment of other less important activities.

Those few renegades who are throwing and attending house parties need to get a grip of their selfishness and stop endangering others. As for the rest of us, perhaps we need to learn to live with uncertainty; to stop looking for complete consistency at a time when physical, mental and economic well-being are all making competing demands on our politicians.

The science, and the advice that flows from it, may not always be perfect; but it’s all we’ve got. What else can we do but follow it; and keep our fingers crossed.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.