UK energy price crisis is being made dramatically worse by Westminster policies as IMF graph makes clear – Professor Richard Murphy

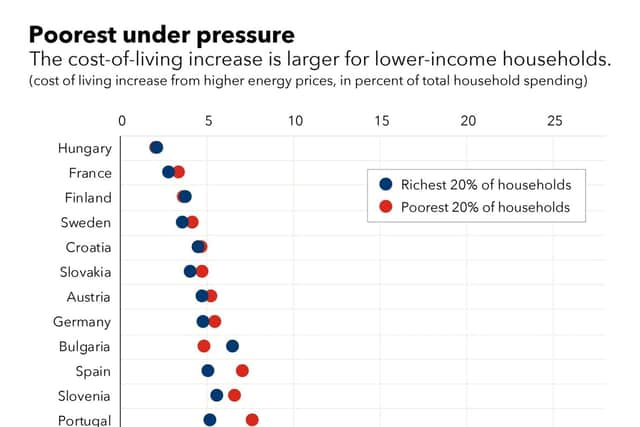

It plotted figures suggesting the likely differing impact of domestic energy price inflation on those in the top and bottom 20 per cent of income earners in European countries for which data was available.

Four things stand out from the chart. The first is in just how many European countries the rate of inflation for those on the highest levels of income is lower than that which the top 20 per cent in this country will suffer in the UK where that figure is forecast to be seven per cent. In many European countries it is five per cent, or less.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSecond, it is apparent that in many countries there is very little difference at all between the rates that will be suffered by the top and bottom income two groups. Germany, France and Sweden provide perfect examples of this: the difference in the inflation rate that high and lower earners will suffer in these countries is very small, and both are lower than anything expected in the UK.

Third, the UK comes a long way down this list because of the massive differential in inflation rates between those on high and low incomes that are likely to be suffered in this country. Whilst the top 20 per cent might see inflation of about seven per cent in the UK, those in the lowest twenty per cent of income earners could experience energy inflation of around 16 per cent, in the IMF’s estimation.

Fourth, excepting Estonia, this differential between these groups is the highest in the UK, and is by far the highest in the larger European countries. With a nine per cent differential, those on low pay in the UK are not going to be just a bit worse off, as happens elsewhere, but dramatically so.

I also suspect that this estimate for the inflation rate for those on low incomes is not consistent across the UK. There are two primary reasons for saying so.

One is that it is colder and darker in Scotland than in the rest of the UK: it is inevitable that more energy is consumed during the Scottish winter than it is in southern England.

A second is that the houses in which those on lower incomes live are usually less well insulated across the UK, but this appears again to be a phenomenon observed more often in the north of England and Scotland, increasing costs the further north you are. The result is that this differential may well be even bigger in Scotland than elsewhere in the UK.

These factors being noted, why is there such a marked differential in the UK, and why are our costs higher for the well-off compared to other European countries before this differential is considered?

The overall higher inflation rate is easy to explain. As a matter of fact, the UK energy regulator, Ofgem, is set up to favour energy companies, not consumers. Whilst gas prices in the UK could be lower than elsewhere because most of the gas that we consume comes from domestic sources, they do not allow for that in their calculations. Instead, they presume we must compete with international markets to buy the domestic gas that we consume, and so pay the price created by Putin’s actions in denying gas to the EU.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith regard to electricity, the situation is even more absurd. Broadly speaking, electricity can be generated from coal, nuclear, hydro, renewable sources and gas in the UK. What electricity we get through the wire into our house does, whatever our energy company tells us, come from a mix of all these sources.

And what Ofgem does is set the price so that the most unprofitable of these production methods will always make a profit, come what may, and then requires all the other producers to charge the same price as that weakest producer. But this is absurd.

If, for example, all of them made electricity for £1 a unit in 2020 and now it costs £2 to make electricity from gas then even though the costs of hydro, nuclear, coal and renewables have not changed the price of all producers will be doubled quite unnecessarily, at enormous cost to us and profit to the energy companies.

That, then, is why our prices are going up more than elsewhere: government regulation guarantees it at present. But why has the price for those on low incomes increased so disproportionately?

First, many in this group are forced onto pre-paid meters. Second, these have the worst tariffs. And third, the standing charges for simply having any meter in your house are disproportionately high for those on low incomes because, relatively, they consume less energy, and those standing charges have increased considerably.

That is most especially true in rural and remote areas, as many in Scotland will also know. We have, therefore, a system not only rigged against consumers in the UK, but against poorer consumers in particular.

What can be done about it? First, we could scrap the standing charge and include it in the tariff. Second, we could require that pre-paid meter users be on the lowest possible tariff. Third, we could make charges progressive, ie the first units of gas and electricity consumed could be at a lower price than the later ones used to heat the swimming pool.

Fourth, we need a Green New Deal that delivers more renewable energy, and which insulates every home better than now. And finally, we need an energy regulator acting on behalf of consumers instead of producers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf Ofgem simply required that energy be sold at the average cost of production across the board, plus a fair profit margin, this problem could be solved and the excess profits now being earned could be eliminated, cutting prices considerably. Why this is not happening is baffling.

In summary, we need not have an energy price crisis in this country. We’ve got one because we have policies quite different from those in other European countries that punish us and the poor most of all. This is our government’s choice.

Richard Murphy is professor of accounting practice, Sheffield University Management School, a chartered accountant and economic justice campaigner. He blogs at Tax Research UK and tweets @RichardJMurphy

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.