Tiffany Jenkins: White male heroes have become zeros

Are there any great men still standing? Is there one left with a reputation that has not been slurred? A hero remaining, whom I can respect? I can’t think of one. Every single great man appears to be tainted: by an association with dodgy political ideas and regimes; the ill-treatment of women; and unprofessional bad practices.

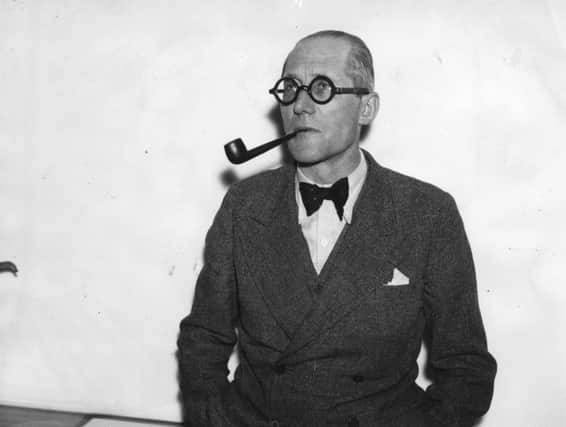

The latest such figure to be pulled off his pedestal is the architect Le Corbusier, the modernist famed for his austere, concrete box-like creations and urban planning. “Passion can create drama out of pure stone,” he once said, summing up his ambition to find emotive, spiritual qualities in his work.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn in Switzerland, Le Corbusier became a French citizen, but his practice – and tremendous influence – extended far beyond the country’s borders, with his buildings constructed in Europe, India and America. He is an architect of international good repute. Deservedly so.

Although he never built anything in Britain, he inspired a moment of modernism in Scotland: the magnificent seminary of St Peter’s, close to Cardross, near Glasgow, intended for turning young men into priests, a role it performed for 14 years after it opened in 1966, was in part influenced by him.

But now the only passion surrounding Le Corbusier’s work comes from those who want to trash his reputation. Two new books about him have accused him of fascist and antisemitic views. These work are damning. An obituary is being written for his good name.

We have already heard how Le Corbusier defaced the interior of E.1027, the seminal modernist village designed by Eileen Gray, a story told in the film, The Price of Desire, and that he had ties to France’s collaborationist regime under Field Marshal Philippe Pétain. But these new publications are the nails in the coffin. The pioneer of modern architecture was, says Xavier de Jarcy, author of Le Corbusier: A French Fascism, an “outright fascist”. The French nation is in shock.

Le Corbusier is only one of the latest in a long list of heroes to be turned into zeros. Anyone who is up there, or who was up there, respected, perhaps idolised, in the past, especially if they are a white male, is not to be respected anymore. It’s like an official edict has gone out. So we are forever reminded that the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who believed in organic architecture – designing structures that were in harmony with humanity and its environment – was a womaniser who abandoned his family, and that his arrogance knew no bounds; Louis Kahn, another American architect, is treated in the same way. OK, it is now said, Kahn may be responsible for a few monumental and monolithic buildings, but the guy had an eye for the ladies, and he had three families – what counts is that he was a disaster of a husband and father. And don’t forget the German avant-garde architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the third and last Bauhaus director. He chose to stay in Berlin after the Nazis gained power – a heinous act which means his great avant-garde work is now discredited.

No-one gets off lightly. And this is not just a trend for demolishing the good reputation of architects –biographies of anyone and everyone tell a warts-and-all story. Richard Wagner was a great composer – but also an antisemite. He can never be forgiven, say some. And what about Karl Marx? We hear more about how he fathered an illegitimate son with the family’s housekeeper while his aristocratic wife was in Europe, pleading with her relatives for financial assistance, than his critique of political economy.

The great work of these once great men is reassessed as a consequence. Well, maybe not reassessed completely, but their achievements are questioned. It’s no longer possible to discuss the accomplishments of someone without mentioning, dwelling on, the nasty side of the man – whichever one it is: the problems of his personality, his hypocrisy, his awful deeds, whatever they were, in a way that threatens to overshadow what he became known for in the first place. The personal is now far more important than the professional and that’s unfortunate.

As with Le Corbusier. A retrospective of his work has just opened in Paris, The Measures of Man, at the Pompidou Centre, which is an ambitious show – partly because it doesn’t talk about the man’s politics. The aim of the exhibition is to return to the architect’s sources, exploring the body as a design starting point for Le Corbusier, who considered it a moving object. Low and behold it is accused of glossing over the past, of ignoring Le Corbusier’s support for fascism. Serge Klarsfeld, a famous French Nazi-hunter, has been wheeled out to argue that “all the aspects of Le Corbusier’s personality” should be included in the Pompidou Centre exhibition.”

But why should it?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is likely that Le Corbusier wasn’t all that nice. He was an elitist. He was comfortable working with nasty political regimes – as were many modernists. And it’s worth knowing this, because it’s a useful reminder that artists are not always on the “right” side, that they can be cheerleaders for the wrong lot. Or for whatever lot wins them work: Le Corbusier also cosied up to communists – he wasn’t all that picky. Or rather, he seems to have been open to the different ideas of his time – many people were – and his views were ambiguous. Undoubtedly it’s very easy to judge him now, decades later, when history has been written. Moral superiority comes with little difficulty when you know what happened, when the verdict has been reached on what was right and wrong.

A great architect does not have to be a good person to be admired and respected. They should be judged – first and foremost – on the merits of their architecture. We should think very hard before we engage further in the process of ruining the reputation of great men. Some of them deserve their pedestals.