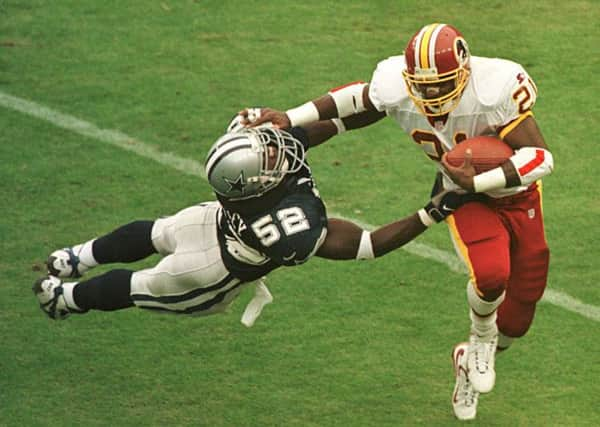

Tiffany Jenkins: Washington Redskins’ copyright

It’s possible that you don’t follow American football all that closely, but if I were to mention the Washington Redskins, you could probably guess that I was referring to a sports team, maybe even an American football team. And if you are American, you wouldn’t have to guess: you would know that is what I meant.

This week, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, which is part of the United States Patent and Trademark Office, cancelled the trademark registration of the name Redskins for use in connection with the football team. The reason for this, they said, was that “a substantial composite of Native Americans found the term Redskins to be disparaging”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome people find the term “redskin” offensive because it has been used in the past when talking or writing about Native Americans in a derogatory fashion. US newspapers in the 19th century referred to Indians as redskins when reporting on the American Indian wars, describing them in hostile ways.

The aim of cancelling the trademark is to prevent the team from profiting from merchandise with their team name on it. The intention in the long run is to make it so difficult to use the name Redskins that the team drop it altogether.

Amanda Blackhorse, one of the campaigners who petitioned for the cancelling of the trademark, said: “It is a great victory for Native Americans and for all Americans. We filed our petition eight years ago and it has been a tough battle ever since.

“I hope this ruling brings us a step closer to that inevitable day when the name of the Washington football team will be changed.”

Even President Barack Obama has voiced his opinion that the team should consider changing their name.

No-one can force the team to drop the name, but it can be made difficult for them to use it. The Seattle Times has said the paper will no longer use the word Redskins. This will not only affect the sports pages, but also the use of the word in other parts of the paper, such as when writing about a school sports team in Washington state, known as the Wellpinit High School Redskins.

Numerous other papers, which include the San Francisco Chronicle and the Kansas City Star, as well as the magazines Mother Jones and the New Republic, have stopped printing the word Redskins when writing about the football team.

It is increasingly common in America and Europe to see these kind of high-profile and vicious arguments over the use of certain words. Many words are already off-limits as a consequence.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf I were to say the n-word here, for example, you would know exactly what I mean, even though it’s no longer possible to write out the word in full: that’s how controversial it is.

Words are powerful and they can have negative meaning and associations, but we should think again about the blanket policing of language in response. Restrictions and bans on what is said and written are illiberal and censorious. They also grant words more power than they have, and they ignore the way language works.

Language is not immutable; it changes and certain words don’t mean what they used to. Just think of how the meaning of the word “gay” has been transformed over the past century. The meaning of words also changes in relation to the context in which they are used: how and by whom. In order to illustrate this point, rather than get into all the other words that are currently deemed hateful and beyond the pale, consider instead one of the least hateful words in the English language: love.

We use the word love in multiple ways. Saying “I love steak” when dining out with friends is quite different to saying “I love you” to a lover for the first time. In the early days of a relationship, saying “I love you” is one of the most difficult and important things that could be said. It is risky; the feeling may not be shared and you may be rejected. However, if you don’t say it at some point, the relationship will not develop.

Saying “I love you” to the same person decades on from that first declaration (assuming it all went well) as you leave for work for the day is a different thing. There is not as much risk involved. It still means something important, so important you have to say it, but it is not as charged or decisive.

And then there is the case of the old dear in the shop who says “Here you go, love” as she gives you back your change, compared to the leering idiot who shouts in your direction: “Hello love.” The former is a nice way to be spoken to, the latter is not.

The primary problem with the attempt to restrict the use of the name Redskins is that the word redskin no longer means, in common parlance, Native American. It stopped being used in this way in the 1960s. It now means the American football team. Google Redskins and you will find page after page devoted to the football team, or about the controversy over the football team’s name.

And we have to ask: who decides what is offensive? Plenty of Native Americans who don’t care what the football team is called.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnd then there are the Native Americans who campaign for the retention of the name. One group on Facebook, “Native American Redskin Fans”, was set up specifically to support the use of the term by the team.

And what about everyone else who could find offence in a word or how they are described? Hillbilly could well be next.

Placing restrictions on words makes words out to be more offensive than they are. It can fix the meaning rather than allow it to change. It is far better to allow language the freedom to evolve and for meanings to change through the use of speech and writing.

Let’s have a cheer for the Washington Redskins!