Tiffany Jenkins: History grants perspective on progress

The world is changing faster than ever and the pace of change will only get faster, is a sentiment heard often in business, education, politics, social and cultural life.

It’s sometimes used as a justification for the introduction of new policy. And it does seem, especially at this time of year, as we look back over the last 12 months, as if a great deal in our world is changing, and quickly. How to keep up?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHistory shows that other epochs witnessed as much change as ours, if not more, and with greater consequence. It’s a useful check, then, to think back to past times, and to compare them to the present. We are witnessing important developments, of course, but nothing like those experienced by generations who came before us.

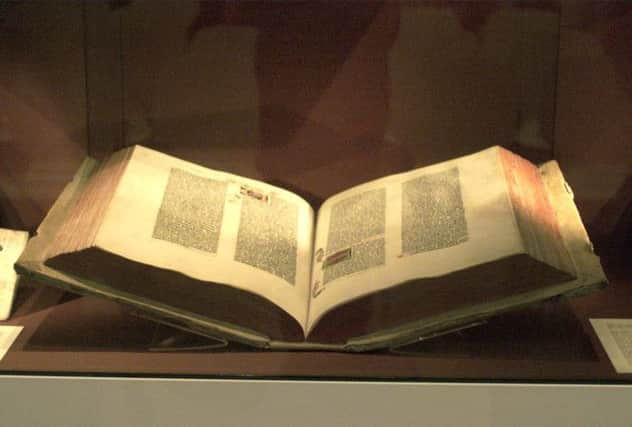

I have spent the holiday catching up on exhibitions, including Germany: Memories of a Nation at the British Museum. It has served as a reality check, an exercise in historical perspective. On show is a Gutenberg Bible, from 1455. As I laid eyes on this remarkable book, I realised that whilst it has become a truism today to say that the pace of innovation is speeding up, that technological changes are transforming our lives as never before, these recent inventions pale in significance when taking a long view.

For over 1,000 years, making a book had meant killing animals to make parchment from their treated skins. This was followed by the laborious work of a scribe, most often monks. Once finished, only the select few could read it, or even see it. That all altered irrevocably more than 500 years ago when Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press, a mechanical way of making books, with moving metal letters, a screw press and a flat plane, and a kind of varnish for ink so it wouldn’t run.

The changes wrought by information technology today are minor compared to those brought about by this early invention. Before it, one written copy of the Bible would have needed 300 sheepskins or 170 calfskins. In the time that it had taken a scribe to copy by hand a few pages, Gutenberg’s press could stamp out thousands, all identical and without mistakes, requiring considerably less work. It laid the foundation for the commercial mass production of books. And, as Neil MacGregor, director of the British Museum, points out: “In a world of advanced IT, we remain unashamedly, irrecoverably, the children of Gutenberg.” It still dominates the way we organise our thoughts online: we choose a “font”, we use a “bookmark” – words used back then in the 15th century.

There is a further, significant difference when comparing the impact of the printing press to that of the internet. Particular ideas were communicated, rather than any old thoughts. The first books Gutenberg printed were copies of the 42-line Gutenberg Bible. They were incredibly popular, with all 200 copies sold before the copying was complete. It was not yet cheap enough to be affordable to the common man, but it was bought up by church parishes and schools. Still available only in Latin, Gutenberg’s Bible was not accessible to the unlearned, but it was an important first step.

And as printing technology spread across Europe it met a time of great religious change and thus played a key role in the success of the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther was the first person to translate and print the Bible in German. The Reformation leader could only preach in person to a small number of people; the printed word spread his message to thousands more, contributing also to the development of the German language. Knowledge and opinions spread like never before. As did dissent: no longer could these ideas be controlled centrally. Medieval Europe was transformed. With the internet, opinions are spread, but few are as challenging or influential as those of the time of the Reformation.

With advances in science, less than 100 years later, Copernicus dared to suggest that the Earth was spinning around the sun: a new, threatening theory, now fundamental to our understanding of our planet and the universe. As for other large-scale changes, consider the political revolutions: the English Civil War, the French Revolution, the American Revolution and the Russian Revolution. Followed by the world wars. And male and female suffrage. Major change of the social order in a very short space of time. I could go on.

Today, the rate of change is slow, especially compared with that of the early and mid-20th century. Politics is now much the same: a competition for the centre ground, with a few blips of hope that fade away into lost dreams. And take travel. Man once relied on horses and boats, which were replaced, in the 19th century, by railways and the steam ship. Soon after, the car took to the roads and airplanes to the skies. Then, Concorde. More people could travel faster than ever before. The world shrunk. In comparison, we are standing still. Concorde has been decommissioned. Some train routes today are slower now than they were in Victorian and Edwardian times. Sure, we have lots of fancy computers, but these are only slight advances in innovation: different sizes, different colours.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWe should question this idea we have currently, that the world is changing faster than ever. It seems to have emerged some 30 years ago when futurist Alvin Toffler described the effects of “too much change in too short a period of time” in his book Future Shock. Toffler warned that people exposed to the rapid changes of modern life would suffer from “shattering stress and disorientation”; they would be “future-shocked.”

But it would appear that the perception of change, the concern that it is out of control, does not meet with reality. Perhaps we are just more fearful of change. And yet, looking back, it is clear that much that was good came from trying to make change happen. It is something we should try again in the new year.