Tiffany Jenkins: Art is not for healing the sick

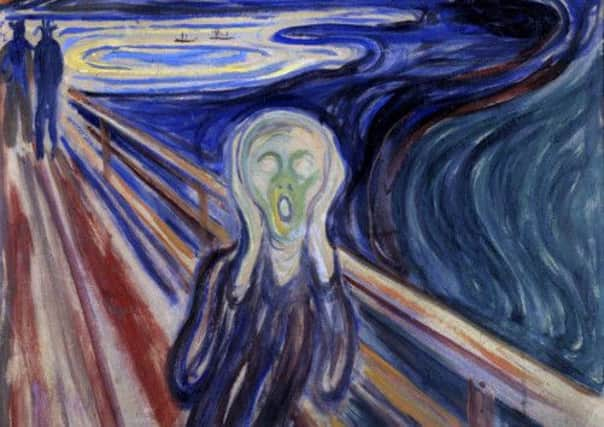

Expressionist painter Edvard Munch’s The Scream depicts a desperate anxiety and horror with life that most of us have experienced. It is also one of the most recognised and reproduced paintings in the world, which suggests that people want to encounter this darkness. We do not always feel, or want to feel, happy or content when we experience art. It can cause and be created by pain, anger and outrage.

The impact of art has been debated for centuries, from the fifth century BC to the present day. For Plato, the philosopher writing in Classical Athens, the arts, especially poetry and theatre, had a corrupting influence. In The Republic, he argued that as art imitates physical things, which imitate the Forms (abstract properties or qualities), art is a copy of a copy and leads us away from truth towards illusion. The arts, he also advanced, appeal to the irrational and emotional parts of the person, which is a problem, especially with the impressionable. Thus, to train and protect citizens for an ideal society, the arts should be controlled. Plato proposed banishing the poets and playwrights out of his ideal republic, with music and painting censored.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe assessment of art as having a negative impact has a long tradition, but it is one that is now thoroughly out of fashion. Today, we hear a great deal about the positive impact; the good the arts do. Along these lines, one argument outlines that the arts stimulate the economy, an agenda that has been much criticised, and rightly so. Another example of the positive impact idea, but one that is increasingly dominant and unchallenged, is that the arts make us better. Not better people – that was the view held in the 19th century – but healthier people.

The possible health benefits of the arts have received increasing attention in recent years. Multiple initiatives have been set up in this area by government, health practices and arts organisations. While there is history of providing paintings and sculpture in the healthcare environment, such as the work of charities like Paintings in Hospitals, founded in the late 1950s, there is an important shift towards the perceived power of the arts to actually improve health – rather than just create a nicer environment for the sick – that has taken place in the past ten to 15 years.

A recent Scottish Government report, which concludes that engaging with culture and sport is good for you, is a case in point. Entitled Healthy Attendance: The Impact of Cultural Engagement and Sports Participation on Health and Satisfaction with Life in Scotland, the executive summary begins with the following statement: “There is consistent evidence that people who participate in culture and sport or attend cultural places or events are more likely to report that their health is good and they are satisfied with their life than those who do not participate.” It was widely reported on along the lines: “art is good for the heart” and “culture is good for your health”.

When a report comes along that says what different sectors in search of funds and legitimacy would like it to say, it’s worth taking a second look. Examining the study closely tells us very little about the positive impact of culture and sport and certainly much less than is implied. Crucially, the implications and conclusions drawn from it are questionable.

A central problem with the study is that the categories used are very broad. Participation in a cultural activity is defined as taking part in at least one activity in the previous year, including: reading for pleasure, dancing, a visit to the cinema, live music and crafts. Sport is equally broad and includes: recreational walking for 30 minutes in the previous four weeks and snooker – that highly strenuous activity. These definitions are so generous and inclusive that it is difficult to assess the impact of involvement in these different activities.

In addition, the terms “life satisfaction” and “good health” are nebulous and subjective. It is hard to get to grips with the meaning of such positive or negative self-reporting by individuals. What does “life satisfaction” mean; is it even a good thing? If people say that they feel healthy, are they necessarily so? If they feel unhealthy, are they? Finally, the study is cross-sectional and cannot determine causal relationships.

This report has the feel of advocacy research. That is, it appears to be conducted to advance the case for supporting the arts. It is one of many that try to hitch the impact of the arts to whatever is the policy objective de jour: the economy, social inclusion, education, and now health. But finding that cultural participation does what policymakers would like it to do is not in the best interests of culture. Nor, as it happens, in this instance, is it in the best interests of our healthcare.

The assumption that art is good for our health and life satisfaction, or that it should be, is suspect. It is not the role of art to act as the drug soma from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. If improving our wellbeing is an explicit aim of the arts, then there is a risk that artists’ work becomes tied to the demand to produce positive outcomes. What if it doesn’t, or has the opposite effect? What if it reminds us just how bleak life can be? The consequence of turning the arts into a healing instrument is that they could lose the capacity to disturb and disrupt.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHeather Stuart, chair of Vocal, the association of council culture and leisure managers, commented in response to the report: “There is no doubt culture and sport services are effective preventative medicine.” But we have to question the notion that health problems can be addressed through culture and sport. While there is no doubt in my mind that to a limited extent both are moderately good for me, at a policy level, such an approach can end up reducing health problems to individual psychology and laziness, steering policymakers away from making more ambitious improvements in our quality of life and medical care.

We do not need the promise of good health and life satisfaction to support culture. And culture is not the solution for our health problems. The arts are no painkiller.