The strange case of the not very good German spy who made Scottish legal history - Susan Morrison

For weeks he’d been watching a man named Graves, who claimed to be a doctor. He was doing some training in Edinburgh.

Dr Graves had been a busy man. He’d visited the offices of Burroughs Wellcome & Co, the ancestor of today's pharmaceutical giants Wellcome, and asked that the very newest literature be sent to his Edinburgh address. He also told them he hadn’t received a diary from them since 1909. Clearly the good doctor enjoyed a freebie just as much as the rest of us.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was terribly outgoing, and well up for some Glasgow banter. When the Assistant Manager of the Central Station Hotel, Alfred Morris, took him to the Art Club one evening, he introduced his guest as the German spy. “Many people in the hotel knew the joke,” he said.

Detective Inspector Trench wasn't laughing. By that April evening, he was ready. Graves had been called to the telephone. In a move that would have warmed James Bond’s heart, Trench stepped smartly behind his prey and pinned his arms to his sides.

This, he said, was to prevent Graves disposing of any valuable items that he had about him, such as the book in his left hand about the history of the Forth Bridge, which just happened to have a map showing the Navy Base at Rosyth. They found a notebook in his pockets with some pages stuck together. Trench took out his trusty knife and slit the leaves apart. There they found pages of written in code.

Dr Graves, the German Spy, was so busted.

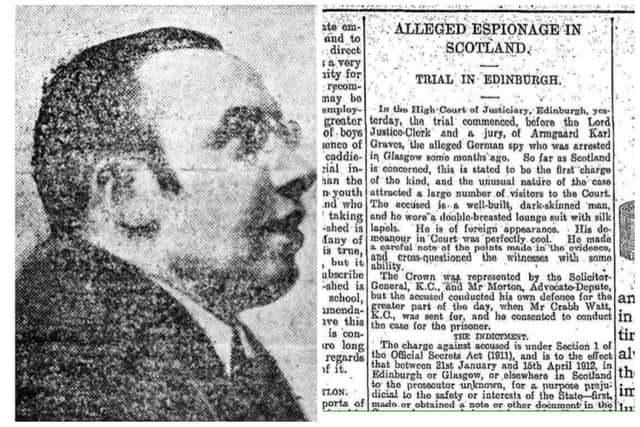

Trench knew all along his suspect was no doctor. Armgaard Karl Graves was a German Naval Intelligence. And he was about to become the first person to be tried in Scotland under the new Official Secrets Act (1911).

The trial in the High Court was a sensation. Even The Scotsman, a newspaper not given to hysteria, admitted that ‘the unusual nature of the case attracted a large number of visitors to the Court’. The accused, they reported, was a ‘well-built, dark skinned man’ wearing a ‘double breasted lounge suit with silk lapels. They also noted he was ‘of foreign appearance’ and ‘perfectly cool’.

He pleaded not guilty, and elected to represent himself. The Lord Justice Clerk who seemed to regard the grubby business of espionage as slightly beneath the dignity of Scotland's courts, said that was an unfortunate thing to do, probably bearing in mind that the prosecution was an impressive tag team of the Solicitor-General and the Advocate-Depute. Graves was assured that every assistance would be extended to him, and that included calling in last-minute legal representation later that day.

Graves may have been a spy, but he wasn’t a particularly good one, even though he did try to create a believable deep-cover identity as a doctor. He’d answered an advertisement for a locum in Leith, but Dr Mackay of Ferry Road said he didn’t like him much and didn’t give him the job. He didn’t care for the tone of the accused’s conversation, not forgetting the 'foreign element'.

He’d been rumbled straightaway. Chief Constable Ross got the nod from British intelligence to keep an eye on him as soon as Graves rented a room from Mrs MacLeod of 23 Craiglea Drive in February of that year. Mind you, Graves rather gave the game away by asking her son William if he had a geography book and could he show him where they built ships on the Clyde and where was the naval base on the Forth? Mrs MacLeod was so alarmed that she let the police go through his pockets when he was out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis code was easily cracked. Admiral Thomas Adair, RN (retired) was shown translations detailing ships arrivals, how ships were cleared for action and which ships were out on manoeuvres, including submarines..

Graves appeared to have some impressive top secret information for his spymasters.

He knew that Beardmore and Sons were delivering navy guns from their factory at Parkhead.

Secret? Stuff and nonsense, announced Admiral Adair, who seems to have taken a slightly breezy attitude to the proceedings. That information was freely available in ‘Brassey’s Annual’, a kind of trade journal of the time.

Why, even the information regarding the vessels and their movements as detailed by Dr Graves was well known enough to be in a German book about navies of the world, which was shown to the Admiral, who said he didn’t know that particular book, and rather gave the impression he wouldn’t give it house room.

Would this information be of use to any nation we went to war against, he was asked? Yes, the Admiral replied, testily, we can imagine. If we went to war with Switzerland, and if the Swiss were told where a British squadron was, then yes, that might be useful. The Scotsman reported laughter in the court.

The jury took 20 minutes to find the spy guilty. The Lord Justice Clark noted that this was the very first trial of its kind in Scotland, and he was not inclined to sentence the prisoner to penal servitude, but noted his English counterparts had been slapping serious jail time on spies. He limited the sentence to eighteen months.

On the whole, everyone seemed very satisfied. Graves even commended the court for his good treatment. The German Spy was banged up and Britain still ruled the waves.

It was 1912. In a few short years, the Royal Navy would sail from the Forth and face the German fleet at Jutland. Fourteen ships were lost, along with 6,000 men. No-one was laughing then.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.