The real lesson from the miners' strike in Scotland - Tom Wood

Thirty five years ago we were coming to the end of the last miners’ strike - a long hard year.It was a dark chapter in our history, communities pitted against each other, resentment and fear of unemployment casting a cloud over our much of our industrial heartland.For miners and their families it was seen as a life or death struggle with a strong hint of class war.For police men and women it was a tough unpleasant job that none of us wanted to do. Those who were not dragged from their usual stations to police the picket line, toiled on long shifts to cover for those who were. Our traditional model of community policing hung by a thread that year.None of us joined to police labour disputes but taking the rough with the smooth, as a disciplined service, we did our duty. We were sworn to uphold the law and permit peaceful picketing, while guaranteeing the right of individuals who wanted to work, to go about their business unmolested . It was hard but straightforward.But throughout, there was a deal of sympathy for many miners, decent working men, many of them friends and neighbours, who we knew were fighting for their way of life.And so, over that long and weary year our two tribes police and miners confronted each other daily in a set piece. In the east, the action was at Monktonhall, Polkemmet but mainly at Bilston Glen - the jewel in the crown of the Scottish coal industry.Policing tactics varied across Scotland and were very different in England. Here there was no national coordination or political direction.And we we were fortunate.

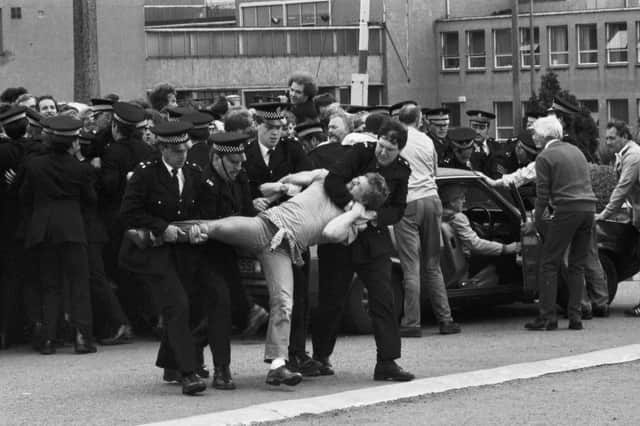

In the Lothians we were well led. Both our senior officers on the ground were good men and knew the mining communities well. One had been born and raised in a mining village, the other had been a miner - a Bevan boy at the end of the war. Our chief constable, by far the finest of his generation, guarded his operational independence and ensured a measured approach. No horses, dogs, batons or shields were ever deployed at Bilston Glen.But it wasn’t a picnic either, there was violence, especially when visiting pickets showed up.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNor was it all just push and shove, over the year in Lothians there were 350 complaints of intimidation and nearly 500 arrests. And there were injuries on both sides, 55 police men and women were seriously injured, some with broken bones and ligament damage.It was all a long time ago but now this dark chapter has been revisited with the publication of John Scott QC’s Independent Review into “the impact of policing on affected communities during the 84/85 strike”.It is a good report, balanced and insightful and we should be thankful that Mr Scott and his team stretched their remit to take in the bigger picture.

It was never only about policing. Rightly the review has considered wider issues around the whole justice system, the role of the unions, the coal board and the Government.The single recommendation of the review is that pardons be considered for miners convicted once of simple breaches of the peace but then sacked and blackballed by the coal board. Personally I cannot quibble with this, the extra judicial punishments meted out to these men by their employers were clearly spiteful and excessive.But for me the real lesson from the miners’ strike was not about what happened on the picket line but what did not happen afterwards.The failure to invest in new jobs and training in many mining communities condemned them to decades of despair and decay.It is difficult, now in the 21st century, to imagine another major industrial dispute like the miners’ strike. But in a post-carbon post-Covid world the effective management of post industrial decline is a skill we may still need.Tom Wood is a writer and former Deputy Chief Constable. In 1984/5 he was a Chief Inspector in Lothian & Borders Police.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.