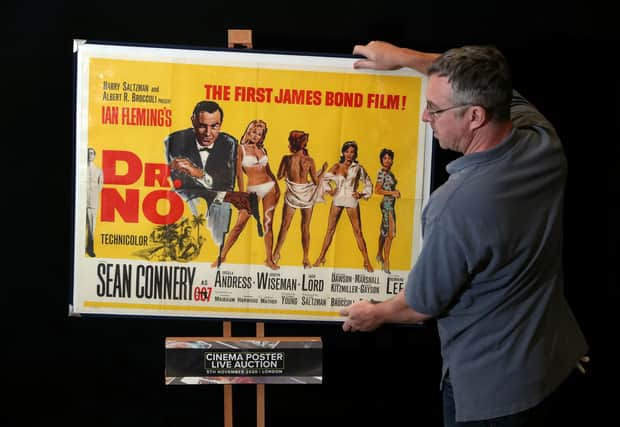

James Bond: Will a physically imperfect 007 ever face a handsome supervillain or will out-dated stereotypes continue? – Alastair Stewart

Nearly every one of the official films features an antagonist with a disability, disfigurement or mental disorder. The movies are iconic, but they are the ground zero for a perpetuated stereotype.

So rife is the trope that the British Film Institute (BFI) announced in 2018 that it would not fund movies with villains with facial scars. The decision supported the #IAmNotYourVillain campaign started by Changing Faces, a charity campaigning for people with a visible difference and disfigurement.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs ever, banning something does not explain why it was popular in the first place. Why is such a prevalent stereotype so locked in the cultural psyche?

According to psychologist David Rakison, professor of evolutionary psychology at Carnegie Mellon University, scars scare us. We desire an attractive and symmetrical face because it epitomises health.

Marked faces make us think of illness. Scars remind us of vulnerability and might suggest a person lives outside of accepted human behaviours.

Researchers from the University of Texas analysed the facial features of 10 classic movie villains and compared them to 10 classic movie heroes.

They found that 60 per cent of the villains had dermatologic conditions: scars, exaggerated wrinkles, dark circles and skin discolouration compared with none of the heroes.

Since time immemorial, physical impairment has been a source of pity and fear in stories. For movie writers, deformity and social exclusion are a dream package to explain good or evil.

They are visual cues akin to an ominous music motif. Fiction and mythology are replete with such figures as the Fisher King, Richard III and Caliban. There is Hephaestus and Medusa. Quasimodo and the Phantom of the Opera. Darth Vader and Freddy Krueger. It is the same thing over and over.

If you go back far enough, the trend dates back to the silent films of the early 1900s. Filmmakers used less than subtle visual prompts to distinguish between good and evil.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNosferatu (1921) features a disturbingly deformed and hairless Count Orlok. The Man Who Laughs (1928) was the inspiration for one of the most iconic and scary comic book villains ever created (I won't spoil it).

The James Bond movie franchise has popularised the cliche to excess. But the film baddies are almost comedic physical adaptations from the psychological 'deviations' and 'perversions' found in the source material.

Ian Fleming was a fetishist, a voyeur and a macabre rubbernecker. His villains and henchmen are all rooted in their sexuality, or lack thereof, and racial stereotypes. Most are sadists. “All women want to be raped,” said Fleming's only female protagonist in The Spy Who Loved Me (1962).

Bond's genitals are ruptured with a carpet beater in Casino Royale (1953). Felix Leiter is maimed by a shark in Live and Let Die (1954), with just the hint it took more than a leg. Pussy Galore is a lesbian who needs the right man to cure her ‘affliction’ in Goldfinger (1958).

An Italian mobster walks around with an electric shaver because of a perpetual five o'clock shadow in Goldfinger. Oddjob has a cleft palate. Live and Let Die is riddled with “negro” and “negress” and wretched portmanteaus like “chegro”. Mr Wint and Mr Kidd are vicious killers and are judged to be gay because of their flamboyant hypochondria in Diamonds are Forever (1956).

It's ironic the movies place a sculpted perfectionism on the Bond actor – his book counterpart sports a long scar on his right cheek. And Blofeld has no face wound, and Scaramanga has no third nipple. There is no Jaws with his metal teeth. Most villains are simply too fat, too small or too bald with a penchant for pain.

None of the stand-out villains of the last century are as stereotypical or more omnipresent than the Nazis. Christine Lokotsch Aube has written that the root of this cinematic phenomenon may be found in Hollywood's anti-German imagery during World War II.

It continued afterwards because the Nazis provided such a distinct vision of evil. Beyond the efficiency, the coldness and the leather jackets, there's the scar, eye-patch or wound. It's on a par with stock characters in the Nehru jacket or Mao suit with a propensity for exotic pets.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it's the scar that goes back even further to Germany's academic fencing tradition. 'Mensur scars' were deliberately sought facial cuts and were worn as a badge of honour.

They were not so severe as to leave a person disfigured or bereft of facial features. They were fashionable among upper-class Austrians and Germans (and some in Central European countries) from the early 1800s.

Otto von Bismarck said they were a mark of bravery, and courage could be judged “by the number of scars on their cheeks”.

With some irony, it was Hitler who banned the practice. Legislation on duelling was tightened in 1937 after a party member died. In many First and Second World War portraits, there is a raft of scars on the left cheek as most fencers were right-handed.

Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, the chief of Reich security, had Mensur scars. Both looked like textbook villains. It is hard to believe that Fleming and other soldiers who became cinema makers and writers wouldn't know about the practice. It went out of fashion from the 1950s, explaining why it's been largely forgotten.

With the 25th Bond movie due out in September and the 60th anniversary of the film series coming up next year, the franchise needs a better class of criminal. Audiences want to be surprised. Casting news and a foreboding facial scratch can give the game away, but it doesn't always have to.

Alastair Stewart is a freelance writer and public affairs consultant. You can read more from Alastair at www.agjstewart.com

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.