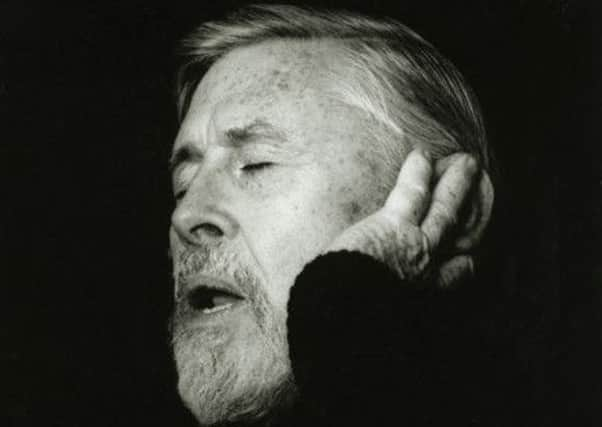

The godfather of folk: Ewan MacColl

A DROOCHIT night in the mid-1980s; the rain is hammering off a giant marquee in York. Scottish musician Alison McMorland is sharing a nearby Portakabin with behemoths of the folk revival, Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger. MacColl has been ill, is not long out of hospital, but no allowances have been made for his frailty. There are no steps down from the Portakabin; getting out requires a jump down into muddy grass. And getting up on to the stage is like clambering on board a ship. Nervous, McMorland opens the concert. MacColl and Seeger, who have been partners for almost 30 years, stand at the back to offer support. Now it’s their turn; Seeger grabs MacColl’s hand to help him up, says, “Here we go,” and they run together to the front of the stage, where they are greeted by an ovation.

When McMorland tells this story, her voice is full of warmth; her relationship with MacColl dates back to the 60s, when her husband, Geordie McIntyre, ran a Glasgow folk club, and she herself performed at the Singers Club, MacColl’s legendary London venue where the enduring image of the man as an unyielding dogmatist was forged. But that night in York, McMorland says, the audience’s affection was unmistakable. “The crowd was huge and everyone was singing along. Afterwards, the audience [some of them ramblers who had joined him on the mass trespass of Kinder Scout in the Peak District in 1932] was thronging round him. It was a privilege to witness.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOthers of course, have different memories. Some recall MacColl and Seeger in London ruling the folk scene like check-shirted Perons; in their club, performers were forbidden to sing in any dialect other than their own. Folk legend Shirley Collins was told to stop painting her fingernails pink. Jacqui McShee, a member of the folk-jazz band Pentangle, was too scared to perform there. “If someone was late returning after the interval, Ewan would make a point of singing something long and you wouldn’t be allowed to take your seat until after he’d finished,” she laughs. If, ultimately, MacColl’s style – the goatee beard, the sitting the wrong way round on a chair, the finger in his ear – came to be lampooned, McShee figures, it was nobody’s fault but his own.

Today, MacColl is one of 20th century music’s most divisive characters; online forums continue to feature bust-ups between those who trumpet all he did to stimulate the folk revival and those who see him as a hypocrite, a man who imposed his dogma on everyone but himself. Yet only the most churlish critic could play down his impact on post-war British culture. A political agitator, playwright, producer of avant-garde radio documentaries and champion of traditional music, MacColl gave voice to the working classes and contributed to the Scottish Renaissance. The Theatre Workshop (which he co-ran with his first wife, Joan Littlewood) was bringing productions to northern Scotland long before 7:84 was formed. And though Scotland had its own flourishing folk scene, presided over by the likes of Hamish Henderson and Norman Buchan, he not only rediscovered old Scottish tunes, he added some more of his own to the canon. That’s without considering his more mainstream legacy: a series of classics such as Dirty Old Town and The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face, which (much to his posthumous chagrin, no doubt) has been covered on The X Factor.

Next Sunday – which is both Burns Night and the centenary of MacColl’s birth – giants of the folk world including Karine Polwart and Martin Carthy, partner Norma Waterson and their daughter Eliza Carthy will take part in a tribute concert, Blood and Roses, in Glasgow’s Royal Concert Hall as part of Celtic Connections. They will be joined by The Blue Nile’s Paul Buchanan and Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker. Today, MacColl’s work will be celebrated more intimately – at a sell-out concert staged by the Glasgow Ballad Workshop; there, McMorland and Geordie McIntyre will perform alongside Anne Neilson, Bob Blair (who belonged to MacColl’s famous Critics’ Group) and Adam McNaughtan. “I don’t think that anybody reasonable could deny MacColl’s contribution,” says Neilson. “He was a consummate performer, but when you went to one of his concerts, it wasn’t all about his work because he unearthed all these traditional songs. He sang them when they weren’t fashionable. He made them attractive and brought them to life again.”

The fact MacColl and Robert Burns – fellow bards, revolutionaries and possessors of messy love lives – share a birthday is so apposite that, if it hadn’t already been true, MacColl might well have made it up. His Scottish roots were genuine, of course – his father, an iron moulder and militant trade unionist, and his mother, a charwoman, were both Scottish – and he grew up among Scottish emigrants in Salford. But such was MacColl’s desire to place himself in a certain geographical and social context, he emphasised, even exaggerated his links. When he needed to change his identity, after deserting from the Army in the Second World War, he took the name of a 20th century Lallans poet and he did nothing to dispel the myth, perpetuated by his friend Hugh MacDiarmid, that he was born in Auchterarder.

There was no need for MacColl to embellish his life story; the reality is mind-boggling enough. Born James Henry Miller, MacColl left school at the height of the Depression and joined the Young Communist League (YCL). His commitment to Marxist ideology endured and he saw literature and music as a medium through which his political vision could be realised. This commitment led MI5 to open a file on him and Special Branch to keep watch on his home.

Self-educated in Manchester Library, he wrote plays of such high calibre they won praise from both MacDiarmid and George Bernard Shaw, and he formed agit-prop theatre groups, eventually teaming up with and marrying Littlewood. After the war, his theatre group – now known as Theatre Workshop – made such an impression in Scotland that decades later residents turning out to watch 7:84 productions would reminisce about their theatrical forebears. In the 80s, 7:84 cemented that link with Clydebuilt, a series of productions which included MacColl’s Johnny Noble.

When Theatre Workshop decided to relocate to Stratford, east London, MacColl severed his links. By now he had already established himself in the folk scene, striking up a relationship with Alan Lomax, the American field collector, who had arrived in Britain in 1950, and with Topic Records. Over the years, MacColl recorded and produced more than 100 albums, many with English folk song collector and singer AL Lloyd. But MacColl had also become friendly with Henderson and Buchan (at one time also a member of the YCL).

Later, MacColl was introduced by Lomax to fellow American, Seeger, and the pair began an affair, though MacColl was 20 years older and married to his second wife, choreographer Jean Newlove. The relationship was the source of much gossip, especially given Seeger and Newlove were pregnant at the same time (Newlove with the singer-songwriter Kirsty MacColl).

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNevertheless, MacColl, with his iconic voice, and Seeger, with her ability to play any instrument she picked up, proved a dynamic pairing. Soon they had set up the Ballads and Blues Club (later the Singers Club) – the first of its kind in the country – and crowned themselves king and queen of the English folk scene. They continued to travel up to Scotland where they made both friends and enemies. Glaswegian singer Alex Campbell was both: he couldn’t stand MacColl’s puritan outlook but when Seeger, already heavily pregnant, faced deportation to the US, he married her to keep her in the country.

In 1957, together with BBC producer Charles Parker, MacColl and Seeger began to work on a series of cutting-edge radio documentaries, known as the Radio Ballads, which gave voice to working class people. The first was about train driver John Axon who had sacrificed his life to save others; there were also documentaries on the building of the M1, coal miners and herring fishers. What set them aside from traditional documentaries is that they were narrated by the interviewees themselves, their voices set against the whirring of machinery and songs written by the pair.

By the time they came to make On The Edge, a study of Britain’s teenagers, Anne Neilson, a member of Norman Buchan’s Ballad club in Rutherglen, had just left school. She was one of several girls interviewed by Seeger in Buchan’s house, while a number of boys were interviewed elsewhere by MacColl. “Peggy was tremendous at establishing an empathy, which meant we spoke unguardedly, which was, of course, the point,” she says.

Neilson already knew MacColl through the folk scene. “I was a bit scared of him. Norman always encouraged you to follow an idea and find out for yourself, whereas I got the feeling that Ewan would just tell you. I remember finding a book somewhere in a shop and thinking: ‘I better tell Norman that book is there,’ whereas I got the feeling that Ewan would have said he already knew.”

MacColl’s rigid approach to performances in his club was one of the issues which put him in conflict with other musicians. Another was his fixation with “authenticity”; he insisted on its importance, yet some believe almost every aspect of his own persona and performance was artificial, from the way he projected his voice to the way he used the music to promote his ideology.

Whatever people made of his attitudes, MacColl’s music kept influencing fresh generations. Alex Neilson, of the Glasgow-based group Trembling Bells, was first turned on to folk music when he came across an LP of MacColl and AL Lloyd singing sea shanties. But, having collaborated with musicians such as Mike Heron, of the Incredible String Band, he is also aware of MacColl’s reputation. “People seem to have very strong opinions about him because he was a founding father of the folk revival in the 60s, but he was so ideological and hardline in the way he conducted himself, he kind of alienated people. I remember Shirley Collins said he was all for humanity, but not really for people.”

In his book on folk music, Electric Eden, Rob Young tries to put MacColl’s perceived puritanism in context; the policy about dialects was one they chose to adopt at their own club, not one they tried to impose on others. But, says Young, as the years passed, MacColl’s vision fell out of step with the times. “As a Marxist, he saw in the 50s the chance to seize the mood and use his platform to create some sort of revolutionary spirit in his audiences. As you get into the mid-60s, however, he is bumping up against the next generation of musical [performers] and listeners, who do want change but want it in way that is not so marked by party lines.” MacColl’s suspicion of Bob Dylan is the stuff of legend. “Dylan is the obvious one, someone who came through as a protest singer, but developed his own visionary language,” Young says. “MacColl was rubbing up against the counter-culture and drugs and all those things he couldn’t see eye to eye with.”

As it became clear his political project was doomed to failure, an edge of bitterness did start to creep into MacColl’s attitude, but he wasn’t consumed by it. As McMorland’s story illustrates, he kept on performing, and there was always an audience eager to hear him. Then there was his love for Peggy and his five children, most of whom followed him into the music business, to take pride in.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNeilson too saw MacColl perform towards the end of his life, this time in Glasgow. “He took his usual position on stage. Peggy was beside him playing and she was very attentive and it turned out that he knew he was dying, really. It wasn’t said overtly, but they finished with The Joy Of Living – it’s a beautiful song he wrote when he knew he didn’t have much time left. Norman and Janey Buchan had tears in their eyes. We all did.”

Twenty-five years after MacColl’s death, folk music is once again flourishing and his contribution to its success is being recognised. “He set in place a style that became absolutely central to folk performance in the decades that followed on from the 50s,” says Young. “Whether it was people wanting to copy what he did or people reacting against it, he was absolutely impossible to avoid.”«

Twitter: @DaniGaravelli1