Supreme Court's Uber ruling exposes the reality of the gig economy and should act as a rallying call for democracy in the workplace – Richard Leonard MSP

In a shameful statement after the UK Supreme Court decision was announced, Uber asserted that the ruling only affects the 25 claimants who lodged the case at an employment tribunal in 2016. Rubbish. The judgement goes to the very root of the Uber business model and the 60,000 drivers who work for it across the UK. It has ramifications for the company in the 71 other countries it operates in as well.

It will also have an impact on the wider gig economy which has spiralled out of control since the last recession, and which has prospered during the pandemic as the switch to online shopping and home delivery has skyrocketed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was in the face of these trends that back in 2018 the SNP government set up an Expert Advisory Panel on the Collaborative Economy – the polite name for the gig economy. Remarkably the Scottish government chose Uber to be among its expert advisers.

The panel recommended the establishment of an “agile regulatory environment for the collaborative economy” and called for incubator and accelerator units to increase the supply of gig economy businesses operating in Scotland. It looks like another example of bad political judgement by the SNP.

Many people in bogus self-employment

We know the number of working people classified as self-employed in Scotland has risen to over 330,000. That’s a jump of 20 per cent in a decade. Some of that growth will be the result of newly inspired entrepreneurship, but it’s fair to say much of it will be enforced by the changes to employment practices now confronting anyone selling their labour.

We also know, as last week’s Supreme Court ruling shows, many of those will be in bogus self-employment.

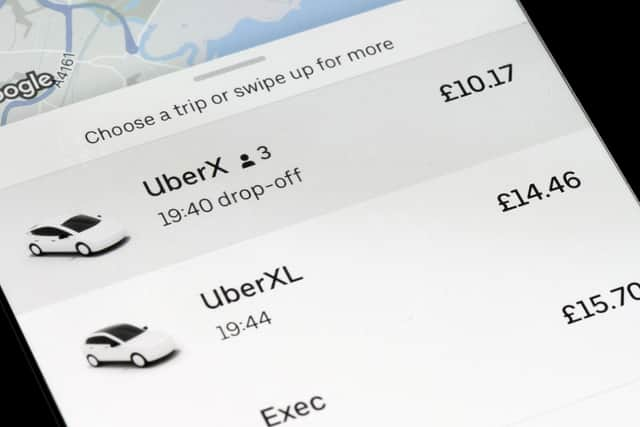

In the Uber case, what the court was interested in was how much control was exercised by the business over its drivers.

It found Uber set the taxi fare and so the driver’s remuneration, set the contract terms between the company and the driver without the latter having sight of those terms, let alone giving consent, stipulated the model and make of vehicle which could be used, took disciplinary action against drivers who turned hires down, described in Uber speak as being “removed from the platform” or “deactivation”.

Judge Lord Leggatt found these measures were “designed to operate coercively”. Uber as part of the arrangement also sacked workers who received poor customer ratings.

The drivers were in the eyes of the court in a “position of subordination”. There was an element of compulsion, even coercion in the disciplinary code. In classic employment law terms, they were in a master-servant relationship.

‘Vulturous greediness’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot only does last week’s landmark case mean Uber will now have to recognise their drivers as workers and so abide by national minimum wage and working-time regulations, including paid holiday entitlement. The company will also be responsible for pension contributions and come within the scope of work-related equality and discrimination statutes: one of the claimants is seeking protection for whistleblowing under the 1996 Employment Rights Act.

Speculation has now switched to whether Uber will also be liable to pay 20 per cent VAT on fares, which could mean an outstanding, estimated tax liability of £1 billion. The company already books commissions through Holland as a tax-avoidance manoeuvre, indeed it was Uber BV registered in the Netherlands that was cited in the court judgement.

Not unusually a company with unlawful working practices, hiring workers on poverty pay, disregarding health and safety laws, also appears to have an unethical approach to its tax returns as well. It’s what Thomas Carlyle referred to as “vulturous greediness”.

There are some peculiarities to Uber’s methods for the control of its workforce. The ordinance that direct communications between driver and passenger are kept to a bare minimum, with the exchange of contact details strictly prohibited is by any measure extreme.

The importance of trade unions

But many of the tests the Supreme Court set will now be applied to other platform companies in the gig economy. One of the useful lessons of the Uber case is the reminder that contractual provisions cannot over-ride statutory rights.

The Uber ruling also demonstrates the importance of trade unions. Workers can have all the rights in the world, but without a union to enforce them they count for nothing. That should not mean an indecent five-year wait in the courts, but immediate redress through negotiation by trade unions with businesses.

The Uber case serves to remind us that the real division in society is not between Scotland and England but between exploiters and exploited.

There has been an emergent class of workers on temporary contracts, on zero-hours, some hired through agencies, others processed through umbrella companies, all with intermittent income and so unlimited insecurity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThese workers are engaged especially in the gig economy, but they can be found in the public sector as well. We know that one care worker in ten in Scotland is on a zero-hours contract.

Extending democratic principles

It is imperative that we tackle these precarious forms of work as we emerge from the pandemic.

But we need to have wider horizons too.

I can’t help thinking that last week’s ruling also highlights the relevance of the ethical socialist argument for the extension of the democratic principle to the workplace. One day we may not have to welcome as glad tidings a court declaration that there is a position of subordination between a person and the business they work for in order to obtain justice.

Imagine if, rather than hired hands, people were treated as participants and citizens in the sphere of work.

That really would help us build a stronger future than our present with its deep-rooted inequalities of power.

How much better a truly collaborative economy would be in place of the sham exposed at Uber.

Richard Leonard is a Labour MSP for Central Scotland

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers.

If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.