Stephen McGinty: Shadow of the Bomb

I ONCE spent a cold winter’s afternoon in the National Archives of Scotland in Edinburgh, leafing through a brown manila folder that confirmed what I had always thought – in the event of a nuclear war I would be toast. Literally incinerated. As a resident of Clydebank, which was less than 20 miles from Faslane, the nuclear submarine base and a bull’s eye on the Soviet Union’s list of military targets, I had no need to fear the onset of a nuclear winter or a slow painful death from radiation poisoning. A blinding flash and all our troubles would be over, along with our lives.

The documents had been drawn up in the 1960s and 1970s in preparation for when the Cold War turned hot. I remember a diagram of the west of Scotland and the concentric circles that rippled out from Faslane with the estimated death tolls associated with each band. I was working on an article about Scotland during the Cold War and, as well as spending a day flicking through civil defence documents, I paid a visit to the little farmhouse outside Anstruther in Fife, beneath which lay the secret nuclear bunker from which Scotland’s military command and civil servants would retreat in the event of Armageddon.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt’s curious how even when faced with such a grim reality, I couldn’t help but frame the visit through the lens of TV and in particular Edge of Darkness, the 1985 BBC drama in which Bob Peck played a policeman investigating his daughter’s murder by elements within the nuclear industry. In one scene he stumbles upon a nuclear bunker in whose darkened rooms was a crucifix. I remember a sinister shot of Christ cast in shadow. Scotland’s secret bunker had a similar little chapel where one imagined the Secretary of State for Scotland bowing his head in prayer for those unfortunates up above.

For many of us who grew up under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, TV shaped our fears. Threads, a BBC drama from 1984, detailed the fate of Sheffield after the bomb had dropped, while Where The Wind Blows, in 1986, was a cartoon adaptation of Raymond Briggs’s comic about how an elderly couple try to cope in the aftermath. Yet I never feared a nuclear war, even when young enough to understand the concept of Mutually Assured Destruction. I just never believed it could happen.

Then, when I grew older and began to read history more deeply, I came to the conclusion that the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, horrific though they were, was justified as it brought to an end the war in the East. The alternative was a US invasion of mainland Japan against a foe that, on island after island in the Pacific, had demonstrated an unwillingness ever to surrender. I guess you could say I’m comfortable with nuclear weapons despite, or perhaps because of, the shadow they cast over my childhood; they weren’t some distant threat, but a gloomy neighbour. I certainly haven’t learned to love the bomb, but I appreciate that with those missiles held in reserve we are unlikely to ever again see mechanised slaughter on the scale of the First or Second World War.

The flip side to that is we could still be wiped out in a nuclear holocaust and what I’ve read this week has shown that we’re fortunate it hasn’t happened already. Command and Control by Eric Schlosser, published by Allen Lane, is a compelling survey of how America’s nuclear arsenal developed and the systems put in place to prevent accidental annihilation. The chilling fact about complicated systems operated by humans is that there will be errors. Mistakes will be made and these lethal weapons require a 100 per cent success rate in containment. If history has taught us anything, it is that we are never 100 per cent correct in anything we do.

When it comes to avoiding an accidental nuclear detonation, we have also been lucky. Take, for example, the crewman on board the B-47 bomber who in 1958 accidentally grabbed the manual bomb release lever and sent a Mark 6 hydrogen bomb tumbling down into the back yard of a family home in Mars Bluff in South Carolina. Thankfully, the nuclear core had not been inserted and so there was no nuclear detonation, just an embarrassing 35ft crater and a lot of dead chickens. Six months previously a similar bomber carrying a hydrogen bomb had caught fire on a runway in Morocco, again, luckily the warhead didn’t detonate. In January 1961 a B-52 carrying a hydrogen bomb blew up while flying over North Carolina, it was later found that all the safety features on the bomb had failed and were it not for a single switch there would have been a nuclear detonation.

Between 1956 and 1961, 12 nuclear warheads were accidentally lost or damaged and it was concern with the risks associated with delivery of a nuclear payload by a bomber that led to the development by the American military of intercontinental ballistic missiles. However, this was not without its own risks, for in 1960 the computers at the North American Air Defence Command (NORAD) based in Colorado stated with a chilling certainty of 99.9 per cent that the Soviet Union had launched a full missile attack on North America. The panic that could have ensued was dampened by a cool head who pointed out that the date of this surprise attack was exceedingly surprising as it happened to coincide with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to the United Nations in New York. The error was eventually tracked down to the Ballistic Missile Early Warning system in Greenland. The system had spotted a shape rising over Norway and concluded that it was a deadly curtain of missiles. It was, in fact, the Moon.

Even after the Cold War had thawed, Russia had its own false alarm in January 1995 that led to Boris Yeltsin opening the briefcase containing the launch codes after being informed that a missile was en route. It turned out to be a weather rocket sent up by the Norwegians to study the aurora borealis. They had informed their Russian neighbours but the message wasn’t passed on to the military.

Eric Schlosser, the US writer whose previous books include Fast Food Nation, points out that all these errors and lucky escapes happened in America, the most affluent and security conscious of those currently in the nuclear club. It is unknown what exactly is happening quietly in Russia, Pakistan, India, North Korea, China and Israel, not to forget those banging at the door demanding admittance such as Iran.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

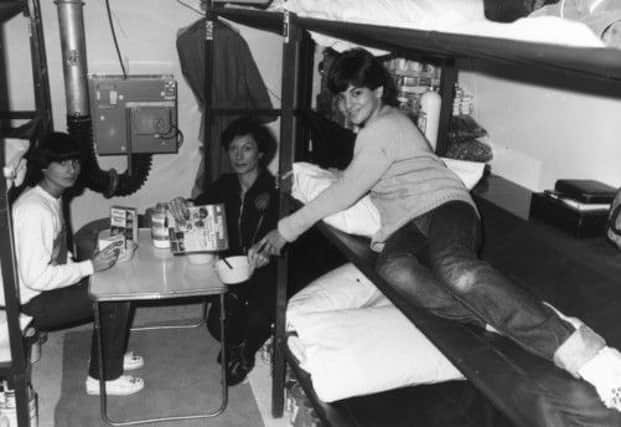

Hide AdAn alternative concern is that a nuclear weapon falls into the hands of a terrorist organisation. For an insightful report on the work being quietly carried out to foil their plans I’d direct readers to a former Scotsman colleague, Eben Harrell. While a reporter for these pages Eben, who is American, secured a visit to Faslane and a tour of a nuclear submarine and what he saw clearly made an impact, for he returned to the States and now works as an Associate at the Project on Managing the Atom in the Belfar Centre at Harvard University.

His most recent report concerned the work of American, Russian and Kazakh scientists to permanently seal off Degelen Mountain in Kazakhstan, which was a site for testing nuclear weapons during the era of the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the Soviet empire, scientists discovered that the site, protected by a solitary guard, still contained as much as 440lb of plutonium – it takes just 17lb to make a nuclear bomb. Over the past 16 years the scientists had negotiated with their governments and have now successfully sealed up the site. Last summer a small stone monument was unveiled which read in Russian, Kazakh and English: “1996-2012: The World Has Become Safer.”

The question is, for how long? General George Lee Butler of the US strategic air command said: “We escaped the Cold War without a nuclear holocaust by some combination of skill, luck and divine intervention, and I suspect the latter in greatest proportion.” But it is Schlosser who gives us all pause for thought: “Right now thousands of missiles are hidden away. Every one of them is an accident waiting to happen, a potential act of mass murder. They are out there waiting, soulless and mechanical, sustained by our denial – and they work.” Oh, and they are just along the road from me.