Stephen McGinty: New facts behind infamous murder

AT the Seacroft Holiday Village in Hemsby there were no clocks on the walls when I visited in November 1994, but there were Christmas trees in each public room and tinsel stretched across the faded yellow walls. In the early hours of the morning, I asked the bored cashier in the canteen about the absence of clocks and the early festive decorations, and all these years later I can still remember almost exactly what she said: “We have ‘festive weekends’ running all year round. Old people arrive on ‘Christmas Eve’ and stay on for ‘Christmas Day’ then ‘New Year’s Eve’. They’re quite popular with people who like to fit in a few more before they go.”

The conversation and the lasting impression of the elderly shuffling into a timeless “Christmas cocoon” left me feeling even more depressed than I already was having come from the Cult TV disco, where a Dalek was attempting to dance with Wonder Woman. In that particular romance, resistance was not useless but highly recommended.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

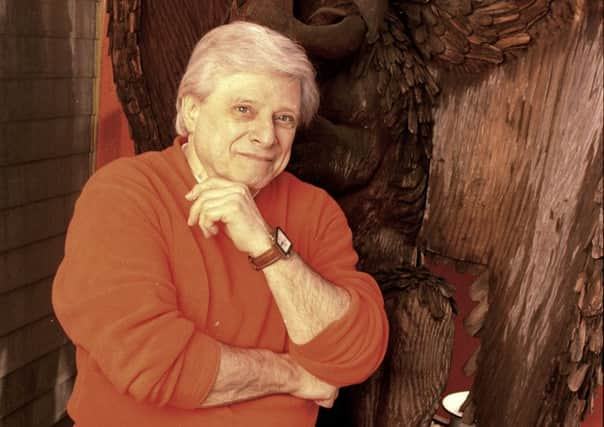

Hide AdOne man had brought me to Great Yarmouth in late autumn, and he wasn’t keen on talking to me. Harlan Ellison, one of the great writers of 20th century “speculative fiction” as he preferred to call it, had accepted the invitation of a free flight, accommodation and a generous per diem, in order to visit the parents of his fifth wife, Susan, who was British, at little cost to himself bar a talk or two about his classic episode of Star Trek, The City on the Edge of Forever.

As it had been more than 20 years since Ellison’s last visit to Britain, I’d grabbed the chance to track him down for an interview, an appointment which proved elusive and finally happened in the last few hours of the final day.

This week I thought of Ellison and his jagged Yosemite Sam-style of speech which was all block capitals and cartoon threats: “BY CHRIST I’LL TAKE A BALL-PEEN HAMMER TO YOU” and in stark contrast to the eloquence and dark beauty of his short stories. One of the stories about which we spoke was The Whimper of Whipped Dogs, which won the Edgar Allan Poe prize for best short story in 1974, and which documents the brutal attack on a young woman in the courtyard of a New York apartment block, whose residents silently watch from their windows as she is stabbed to death. The story attempted to characterise evil as a numinous force drifting up from the killer and swirling around each of the witnesses who did nothing to halt his hand.

The story was inspired by a true crime, one which took place in the early hours of 13 March, 1964, and which has had a dramatic effect on the teaching of sociology and the supposed understanding of human nature.

Catherine Susan “Kitty” Genovese was the 28-year-old bar manager of the E’s 11th Hour Sports Bar and lived with a girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko, in an apartment in Kew Gardens in Queens, New York City.

At around 3am she parked her car in the Long Island Rail Road parking lot and walked the 100 yards to the front door of her apartment. She was approached by a man who attacked her, and as she walked to her home, stabbed her twice in the back.

The man fled when someone shouted out to him, but ten minutes later he returned in a car wearing a wide-brimmed hat and began searching for Kitty, who had managed to drag herself up to the door of her apartment but it was locked and she was too weak to let herself in. He then stabbed her again, attempted to rape her, then fled with $49.

A neighbour, Sophia Farrar, found her and she died in her arms.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA fortnight later, Michael J Murphy, the police commissioner, was having lunch with AM Rosenthal, the city editor of the New York Times, when they got to talking about the murder, one of 636 that would take place that year. Murphy told him: “Brother, that Queens Story is one for the book. Thirty-eight witnesses. Thirty-eight. I’ve been in this business a long time but this beats everything.”

A few days later, Rosenthal ran a story on the front page with a first line which read: “For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.”

The story struck a nerve with a nation concerned about the callousness of urban life and was reprinted in newspapers across the country. It quickly became the focus of the budding field of sociology, with experts seeking to explain how 38 people could watch a young woman screaming for her life and do nothing. Their answer to that very question was what is now the accepted sociological concept of “the bystander effect”.

In both Britain and America the case of Kitty Genovese appears in social psychology textbooks as the perfect example of what is also known as “the diffusion of responsibility”. Sociology academics argue that the case of Kitty Genovese shows that the greater the number of bystanders to a crime, the less likely that someone will intervene on the grounds that each person assumes someone else will take action.

Malcolm Gladwell discussed the concept at length in The Tipping Point and, according to one expert, the Kitty Genovese case remained “the most cited incident in social psychology literature until 9/11”.

The problem for sociologists is that it didn’t actually happen as it was originally reported. A new book, Kitty Genovese: The Murder, The Bystanders, The Crime that Changed America, by Kevin Cook, revealed that instead of 38 witnesses, there was 49. However. all but two of them reported seeing nothing and hearing only indistinct noises which they only associated with the crime afterwards. The idea of a community of the damned leering out the window to watch, an image perpetuated for the past 50 years, is utterly false. Yet mankind, or at least two examples, does not get off lightly. There were two witnesses, but neither of them witnessed both attacks, though each should still have intervened.

Karl Ross, who was drunk at the time, saw the first attack, then called a friend on Long Island and asked what he should do. The friend told him to do nothing. Ross then crawled across the roof to visit a neighbour and seek a second opinion. The second eyewitness, Joseph Fink, also witnessed the first attack then, incredibly, took a nap.

The original publicity in the New York Times may have tarred the entire community of Kew Gardens, instead of two individuals, but it did have several positive effects. The myriad police telephone lines, which frequently led to emergency calls being transferred to the wrong department, were replaced with a single emergency number “911”. All 50 states soon passed “Good Samaritan” laws that compelled bystanders to act by reporting crimes or, if possible, intervening.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’ve known the name Kitty Genovese for more than 30 years, since I first read Ellison’s short story and the dedication, but this week I discovered that of her killer, Winston Moseley, who had risen at 2am and left his wife sleeping, to go out that night with the intention of committing murder. After his arrest and confession to another murder, a number of rapes and 30 burglaries, he was sentenced to death but won an appeal for a life sentence.

He escaped prison in 1968 and sexually assaulted a mother and daughter before being re-arrested. He remains incarcerated today as Prisoner 64A0102 at the Clinton Correctional Facility, having served 50 years of a life sentence. His most recent appeal for parole was rejected last year.

Today, the case of Kitty Genovese still appears in social psychology textbooks as a reported fact, despite the encouragement of the sociological establishment that it now be viewed as a “parable”. I don’t believe “parables” have a place in textbooks and for that readers should turn to Whipped Dogs and Harlan Ellison’s collection The Death Bird Stories.

I think the fate of Kitty Genovese was bad enough without also claiming the world turned its back on her.