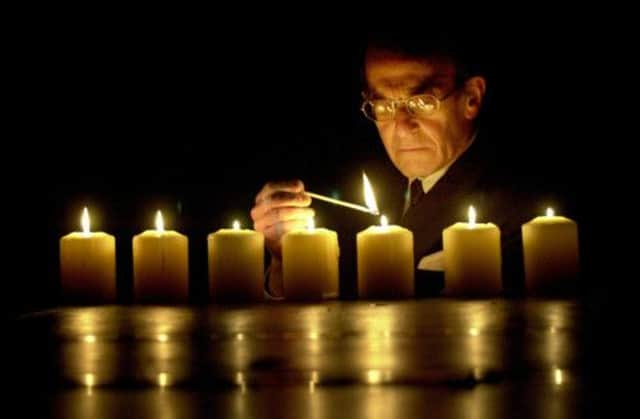

Stephen McGinty: Lights in the darkness

The cobbled stones of Scotland’s cities and the worn dirt tracks and fields of the countryside were not unknown to the feet of the wandering Jew, be they merchant, sailor or tradesman, after all didn’t the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320 declare: “cum non sit Pondus nec distinccio Judei et Greci, Scoti aut Anglici” – “there is neither bias nor difference between Jew or Greek, Scot or English”?

The names of those scattered individuals who drifted across Scotland down through the centuries are long since lost and it wasn’t until 1793 that a Jewish dentist became the first of his kin to decide that it was here, in Scotland’s soil, that he and his wife would greet eternity.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen Heyman Lion purchased a burial plot on Edinburgh’s Calton Hill he would have been unaware that it would become one of the earliest markers of the Jewish community in Scotland.

For the past four weeks, along with a couple of million others, I have been watching the head swivelling, arm flailing gymnastics of Simon Schama as he leads us, like a clean-shaven Moses, through The Story of the Jews on BBC 2. As Sunday will see his winding 3,000 year old story draw to a close, it got me thinking about the quiet, hidden history of Scotland’s Jewish community. In last week’s programme Schama stood in what was once the Russian Pale where millions of Eastern European Jews lived in schtetls, and read on his iPhone a contemporary report from the Manchester Guardian about the butchery of hundreds of Jews in a pogrom in Kishinov in 1905.

Similar reports of children torn limb from limb and the decapitation of the elderly were read by the shocked residents of the Jewish community in the Glasgow Gorbals, which was then almost 10,000 strong. Back then Yiddish was the common language, there were Jewish bakers, tailors, merchants and shopkeepers and a growing interest in Zionism. Fifteen years before, Chovevei Zion, “lovers of Zion” had been founded first in Edinburgh and then, a year later in Glasgow, as a charitable organisation to help Jewish settlers in Palestine, and in 1898 a delegation was sent from Scotland to the second Zionist Congress in Basle.

News of the atrocity in Kishinov boosted attendance at their regular Glasgow meetings. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, a number of Jews from Glasgow decided to return home in the mistaken belief that the Communist revolution would mean a worker’s utopia free from the stain of anti-semitism. Wiser ones headed west and on to America.

At the time the leading figure among Glasgow Jews was (the Rev) E P Phillips who was the minister at the Garnethill synagogue for an incredible 50 years, between 1879 and 1929. Celtic Football Club may have been founded in 1888, but so was the Glasgow Hebrew Benevolent Loan Society which built on the work of the Glasgow Hebrew Philanthropic Society, formed 30 years before in 1858.

The importance of Jewish charity was not only tied in with the faith but to protect Jews from what they saw as the predatory behaviour of Christian charities who would tempt the poor and destitute with food and shelter but were really after their souls and sought to convert them.

Phillips argued against this behaviour and the community sought to provide their own charitable organisations and proved increasingly successful. In 1908 there were only 75 Jewish people in the whole of Scotland on poor relief. By 1910 the Jewish Dispensary opened in the Gorbals with 500 people paying a weekly contribution of a penny.

The first Jews arrived in Scotland from Germany and Holland, but from the 1860s onwards it was principally from Poland and Russia. Their numbers, though rising, were small enough that while there were cases of harassment, there was never the same prejudice as that which greeted the Irish. In the 1850s Edinburgh and Glasgow had communities of equal size but the rising commercial economy in the west meant this did not last long. Jews from Hamburg were drawn to Dundee in the 1870s by the textile trade, with the first Synagogue opening in 1874, Dalry had a small community of Jewish waterproofers by 1880 while Aberdeen’s Jews had to fight off an official complaint by the SPCA in 1893 over kashrut, the kosher slaughtering of animals.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMany were drawn as emigrants to Scotland by the country’s expansive shipping industry with plans to continue on to America abruptly cancelled by ill-health or a change of mind. By 1914 and the outbreak of the First World War there were 12,000 Jews in Glasgow and 1,500 in Edinburgh, this was also the year negotiations began to open a Jewish school in Glasgow. However, the school board insisted on only one hour of Hebrew a day and it was not until 1962 that the first Jewish primary school opened in the city.

It was just before and then after the Second World War that the Jewish community in the Gorbals began to break up as they moved into the city’s southern suburbs. Chaim Bermant, who was raised in the Gorbals, recalled the atmosphere and what it felt like to leave: “There were yiddish posters on the hoardings, Hebrew lettering on the shops, Jewish names, Jewish faces, Jewish butchers, Jewish bakers with Jewish bread and Jewish grocers with barrels of herring in the doorway. It was only when we moved into a flat in Battlefield that I began to feel my exile.”

The early 1960s also saw the arrival of men such as the late cantor, Ernest Levy, who had been born in Bratislava and had survived seven concentration camps including Auschwitz. He arrived at Glasgow’s Central station in July 1961 to join his brother and sister: “For a moment, when I saw Glasgow with its grey, low flying clouds I thought I had made a mistake … but as we drove into Giffnock suburb I fell in love with the entire area, something here had clicked.”

The spectre of antisemitism has never departed, which, unfortunately remains the case in many nations. Today, the unpopularity with some Scots of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians can lead, occasionally, to conflict and there is something deeply depressing about the continued requirement of security guards at synagogues during major holidays. No other person of faith in Scotland requires protection in order to pray.

As the Society of Jewish Communities in Scotland wrote in 2007: “While there are relatively few serious anti-semitic incidents, there is increasingly a climate of hostility created in large part by the demonisation of Israel … criticism of Jews collectively on grounds that are not applied to others is a form of antisemitism just as much as individual discrimination, and this provides fertile ground for more pernicious forms of antisemitism …

“Significant numbers say they do feel more apprehensive about attending events at known Jewish locations and in particular about appearing visibly Jewish (for example wearing a skullcap). Anti-semitic incidents are increasing and Jewish organisations in Scotland have been advised by the police to take measures to improve security … although most incidents are minor, for example, verbal abuse against visibly Jewish people, they do contribute to an increasing perception that Scottish society is becoming more anti-semitic.”

It would be sad if, seven years on, this remains the case or, worse still, if their fears have increased, but despite this, incidents are still lower than the UK average. As David Daiches, the Jewish scholar explained in his autobiography Two Worlds: An Edinburgh Jewish Childhood there are grounds for believing that Scotland is the only European country which has no history of state persecution of Jews.

Yet one thing is for certain, the Jewish community in Scotland is shrinking. The census figures published on Thursday had their numbers below 6,000. Since their arrival, many Jewish people have sought integration without assimilation and this delicate balance is proving ever more difficult to achieve with the rise of secularism and the increasing likelihood of young people marrying out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor organisations such as Lubavitch, which runs an outreach programme in Glasgow with a view to reconnecting secular Jews to their faith, the current situation is a cause for concern: “15 Jewish births a year” and “intermarriage & interdating raging at 70 per cent” states their website, as well as advertising Scotland’s only Jewish Kosher restaurant L’Chaims and a seven-day gourmet kosher tour of Scotland.

Today, Jewish men and women are a proud part of the Scots diaspora with a number continuing to hold an annual Burns supper in Israel, serving a Kosher haggis and lashings of Irn-Bru, which was reportedly described in the Jerusalem Post as a kind of “Scottish champagne”.

On Sunday night, when Mr Schama concludes his epic journey, I may crack a can in celebration and raise a toast to our neighbours. L’Chaims!