SNP's centralising instincts mean Scotland will have to wait for directly elected provosts – John McLellan

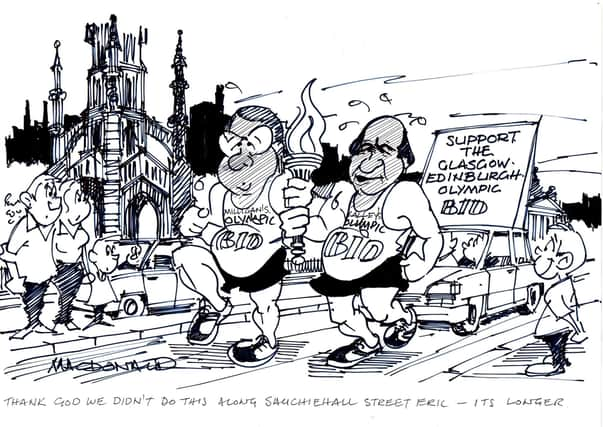

Doomed suggests a proper campaign, but it only really existed in the imaginations of the two ambitious Lord Provosts of the time, Edinburgh’s Eric Milligan and Glasgow’s Pat Lally, the two gentlemen puffing their way down Princes Street in the drawing. The cities were, as they say, never at the races compared to the eventual hosts, Beijing and London, but both men had an unerring eye for promoting their hometowns and were very much the faces of their respective authorities.

Neither were the actual political leaders, but as experienced Labour hands – Milligan has been the old Lothian Region’s convener, and Lally the Glasgow district council leader – both became Lord Provosts of the new unitary authorities in 1995 when regional councils were abolished. Well-known faces, they filled the void while the public got used to the system which gave the 32 new councils full control of local services, instead of split between regions and districts. High profiles led to accusations by opponents and party colleagues alike that they were as interested in promoting themselves as their cities (Lally earned his nickname ‘Lazarus’ for his comebacks after twice being suspended by the Labour party) but at least voters knew who they were.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdForgive the history lesson, but they are the closest we have to the principle of elected provosts or mayors, again mooted as a means to improve public services and accountability, with last week’s publication of a short paper by the Reform Scotland think tank, after it featured in former Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s report on reforms to UK democracy for the Labour Party.

There are good arguments to support the principle, but as it stands it will take more than 12 drummers drumming for a lot longer than the 12 days of Christmas for the Reform Scotland plan to see the light of day. Their proposal is for every council to elect a mayor directly at the same time as the rest of the members, with councillors in their political groups providing scrutiny of whatever policies the mayor and executive team introduce. The Lord Provost would continue to chair council meetings and the position of council leader, currently the head of which ever group is in control, would be abolished. In theory it would create the possibility of the mayor representing a different party to the majority of members, but in practice would produce either the mayor coming from the controlling group or groups, with the public noticing little difference, or a stalemate in which a mayor with different priorities finds it impossible to have a programme approved.

As someone who spent five years in Edinburgh City Chambers, the Reform Scotland model over-estimates the impact of simply swapping the political group leader for an elected mayor and complicates local decision-making with no promise of an improvement to services, while making what is already a poorly understood proportional system even more complicated. Turnout in this year’s Edinburgh council election was relatively good, but 52 per cent of people didn’t vote and of the completed ballots, just over one per cent were rejected. Canvassers on the doorsteps spend as much time explaining the system as they do promoting their candidates.

What could make a difference and avoid voter confusion would be the creation of regional mayors like those covering the English conurbations, electing a powerful figurehead to speak up for groups of councils with mutual interests and provide regional solutions which the current system only manages on an ad hoc basis, such as for the City Region Deals.

A Lothian mayor would have much more influence than the mayors of Midlothian or East Lothian and be able to coordinate services like public transport, which currently works for Edinburgh but less so outlying towns. A Glasgow mayor combining the interests of Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire would be well placed to match investment opportunities with labour and housing supply, and a Borders mayor with a deep understanding of rural economics would be a powerful voice stretching from Stranraer to Eyemouth. There would be issues – Fife could be in a bigger Forth or Tayside region, split between the two, or stand alone as it did in the regional council days – but it would be important not to repeat past errors by lumping together areas with little in common, like rural Argyll and East Kilbride in Strathclyde.

Success would lie in the strength it creates for single-minded individuals with a personal mandate. The role requires challenge, and Labour’s Andy Burnham in Manchester has no problem taking on a Conservative government, and Conservatives Ben Houchen in Teesside and Birmingham’s Andy Street are not cowed because they have the voters behind them and also because the party is accustomed to disagreement. As ex-communities minister Ash Regan knows, in the SNP it’s either Nicola Sturgeon’s way or the highway and this is where it really begins to fall apart. Local administration is a Scottish Government responsibility and, in the big urban areas, where mayors might make the most difference, it would either produce an opponent the SNP doesn’t need or, more likely, another Nationalist bound by the same party discipline so there would be no point running the risk.

At a time when the cost of living tops most priorities, there is no clamour for it, and therefore no incentive for the SNP to abandon a centralising instinct which produced national police and fire services where local accountability is 20 minutes at a policy committee, and its determination to strip social care from councils. If there is to be reform of government, the dogs in the street know what the SNP wants and it’s not local mayors. Today’s Milligans and Lallys will just have to keep running.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.