Scottish independence: Unionists who call themselves democrats cannot deny SNP a referendum – Alastair Stewart

The last decade has confirmed anything is possible constitutionally. But whatever the ruling, it will never resolve the fundamental flaws that lead us here. Two separate political themes have stuck Scottish public political life on repeat.

The first is systemic: how can Scotland get an independence referendum when it returns a government that wants one, but the UK Government repeatedly ignores that mandate and refuses to grant a vote? Since 2011, the SNP has won unequivocal victories in Scottish, UK, local council and EU elections in 2021, 2019, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2012, 2011, and 2009 – the 2014 independence referendum was their only real setback.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdCritics may say you cannot run a campaign on an issue you have no control over. However, if that were true, no progress would ever be made on anything. There has to be some formal recourse to settle a political question that a party has been elected to raise.

The second lies squarely with the SNP and centres on the detailed costs of independence. Some people feel that the SNP's proposals for independence are terrible and lacklustre in detail – to say the least.

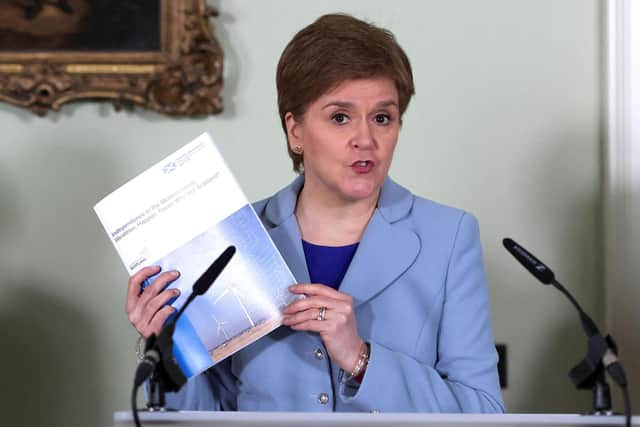

For example the First Minister has been urged to set out the estimated costs associated with physical customs checks "likely only be undertaken on the two main trunk routes between England and Scotland or at rail freight terminals", following her 'Building a New Scotland' policy paper series.

But criticising her plans is not the same as resolving Scotland's constitutional deadlock. This is for the Scottish electorate to judge at a referendum, and it is not for the UK Government to consider if such proposals merit a vote. Polls are part of the equation, but mandates determined by elections are everything. You either believe in democracy, or you do not.

Whatever the Supreme Court decides next week, the debate between policy and procedure will not be going anywhere. How does Scotland get what it votes for, even if it is inconvenient?

Pursuing what is, at the moment, a rogue referendum is a bold unilateral move for the SNP. Still, it does not answer the deficiency in a system that suppresses a central tenet of their party, which happens to keep winning elections. Answer that, and the Union may have a chance.

Brexit was an insult to devolution. It radically altered the 1998 settlement, encroached on pre-defined Scottish powers and forever changed how people viewed the cause and effect of UK Government policy. For most of the Union's history, Scotland's institutions have remained distinct, including education, law and health. Keeping the furniture safe is a constant challenge if your landlord is trying to tear the house down, brick by brick.

The Sewel Convention (where the Scottish Parliament has to assent to any UK legislation that impinges on a devolved area) is not enough to plaster over the severe cracks in the supposed adaptability of the UK constitution. A country in a voluntary union should be able to decide if it wants to remain a participant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe UK Chancellor's autumn statement predictably revitalised the question of whether Scotland could do better under independence. Progression beyond this fixation has much to do with the availability of a constitutional mechanism to ask if that is what the people want. The fact one is not forthcoming is a distraction.

In the run-up to the 2016 EU referendum, policy outcomes were the focus. Not only was a referendum within the purview of the government and Parliament, it simply became a question of timing. Conservative voters – and many across the political aisle – would have rightly called foul if a vote had been promised and then denied.

You may not like the SNP, you may not like their government, and you may think their proposals for independence are bonkers, but that is entirely separate from resolving their repeated electoral triumphs on a platform to have a referendum.

One can be a unionist and recognise something seriously amiss with the system, which cannot resolve such a massive democratic deficit. The second paper in the Building a New Scotland series, Renewing Democracy through Independence, claims that, under the current system, only the UK Government and Westminster Parliament can make decisions about specific issues that significantly impact people's daily lives in areas such as energy and migration.

The diagnosis is correct, but not the resolution. Things can change, but it begins by recognising that the current issue is unavoidable. Three Scotland Acts (1998, 2012 and 2016) have resulted in the Scottish Parliament evolving beyond its initial remit.

What would have happened if a Scottish Lib Dem government called for federalism and the UK Government refused? What would happen next if, election after election, they kept winning on that mandate, but no one listened? Can it only ever be granted by Westminster?

The SNP does not dominate the constitution; they happen to be in power. Parliaments are like black holes; they want more and more control. This is the reality of devolution: our Parliament either exists to serve the people or it survives at Westminster's convenience.

Scottish independence is dangerous. But it is bizarre that a referendum is taken as an issue in an advanced democracy. The ability of a party to act on issues and commitments they were elected on should be a democratic celebration, even if it is on something disagreeable. The denial of this should prompt outrage from any professed democrat.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.