Scottish democracy needs a major audit as the executive grows ever more powerful without compensating oversight – Professor James Mitchell

A survey by Unesco after the Second World War recorded “no adverse replies” on the merits of democracy. It is the hurrah word. Politicians of all shades are keen to stake a claim and often as keen to claim opponents are anti-democratic. This is as true in Scotland as elsewhere.

No doubt if the Supreme Court rejects the right of Holyrood to hold an independence referendum, this will be described in some quarters as anti-democratic. Others will claim the limited binary choice disenfranchises or forces many to choose between two unpalatable alternatives and is thus undemocratic. Such claims should always be treated with scepticism and there is much more to democracy than any single issue, however important.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut leave aside the rhetoric, what does it mean and how do we measure democracy? Is it in crisis as a plethora of recent books suggest? Or is it just that the rise of populists such as Trump, Orbán, Erdogan and Modi suggests the demos cannot be trusted to elect responsible politicians? To what extent has economic dislocation undermined democratic institutions?

As Anthony Arblaster, an old colleague, used to warn, anti-democratic attitudes are “not as moribund as public rhetoric might lead us to suppose”. Demophobia only lies below the surface of much democratic rhetoric. Periods of economic crisis bring it to the surface. Instead of bold claims about democracy that focus on one institution or set of behaviours, we need to consider its multi-faceted nature.

We have seen significant democratic advances in Scotland over the last quarter-century but also little or no progress in other areas and indeed some democratic degradation. While we should be wary of what Saul Below referred to as “crisis chatter”, we can recognise that a crisis is a moment of significant or stark choice.

A longer term approach to these questions in Scotland takes us back to pre-devolution times and the notion of a “democratic deficit”. Eighteen years of a Conservative-run Scottish Office, out of step with public opinion amid diminishing Tory support, highlighted the weakness of acknowledging Scotland as a distinct political entity without accepting the corollary of a distinct elected body. Local authorities were directly elected but lost power and autonomy over this period, contributing to the demand for a Scottish Parliament in the expectation that meaningful partnership with local authorities would follow.

When it first met, Donald Dewar claimed the devolution campaign had drawn inspiration and strength from Scotland’s “great democratic traditions”. It was a “new voice in the land, the voice of a democratic Scotland”. It was invested with much hope. There is no doubt it has provided greater accountability, more opportunities for authoritative and deliberative decision-making, and opportunities for more participation. Its establishment marked a major democratic event.

But Dewar also argued that the parliament was “not an end” but “a means to greater ends”. For some this means gaining more powers, for others deepening democracy and others still saw this as creating opportunities for deliberative democratic policy-making. There is little doubt that Dewar saw devolution as the start of the process of enhancing democracy.

He established a commission under Sir Neil McIntosh, former chief executive of Strathclyde Region, to consider improvements in relations between the parliament and local government. Sir Neil’s report, Moving Forward, was published within months of the parliament’s establishment and is even more relevant today. Some of its recommendations were adopted, including a more proportional system for local government, but many were not and the key message that there should be “parity of esteem” and “mutual respect” is difficult to reconcile with the Scottish Government’s behaviour towards local government today. Scottish central government’s usurping of local power is a major blemish on Scottish democracy.

Therein lies a large part of the problem. The executive branch has grown ever more powerful without compensating democratic oversight. More competences have been devolved enhancing the Scottish Government’s power. The parliament has simply not kept pace just as power has been sucked up from local democracy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTransparency is key in any democratic polity. Many ideas raised prior to and in the early years of devolution have been abandoned. Scotland’s non-departmental public bodies remain vital, spending vast sums, yet far too little scrutiny has been paid to appointees; fear that scrutiny might put off good citizens coming forward is an excuse as feeble as it is predictable.

It is extraordinary that the appointment and activities of special advisers are paid so little attention given their potential power. Another feature of openness is the odd and little-commented-upon circularity and insularity of party insiders/advisers/lobbyists/media commentators/columnists. Given the manner in which elected representatives are chosen is to a very large extent dependent on party democracy, we spend insufficient time examining the selectorate and selection processes.

In looking at Scottish democracy, we need to focus not only on altering the executive/legislature balance, empowering local democracy, the health of our media, and the state of internal party democracy. This infrastructure is vital but, at its heart, democracy is a key element of civic equality. One person, one vote is its most obvious manifestation but is rendered meaningless when wealth is unevenly distributed, giving some interests inequable access to power. A more democratic society needs to be a more equal society. Fraser of Allander’s recent report on health inequalities can be read as a report on the state of democratic politics. That too should cause us concern.

That well-worn cliché about devolution is relevant: democracy is not an event but a process. One leading theorist argued democracy is a “never-ending quest”. Perhaps that is what Donald Dewar had in mind when he addressed the first meeting of the Scottish Parliament. It’s time we had a full audit of democracy in Scotland.

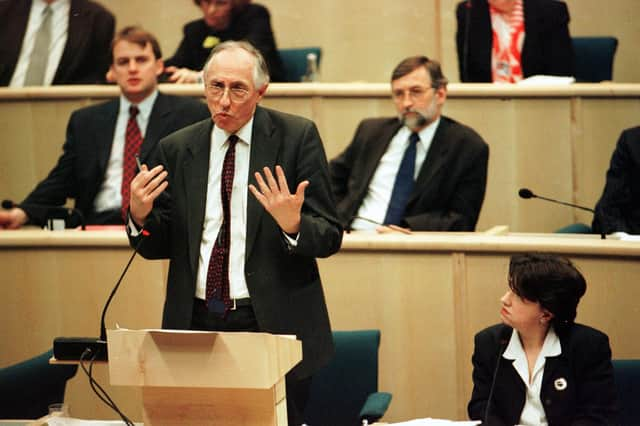

This article is based on the inaugural State of Scottish Democracy lecture by Professor James Mitchell, given at Govan’s Pearce Institute yesterday

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.