Scots and Gaelic languages should be preserved just like Scotland's wildcats and crossbills – James Robertson

Twenty years on, Itchy Coo has produced more than 80 titles, ranging from board books to graphic novels and collections of poems, fables, fairy tales and stories. The list includes many translations of works by the likes of Julia Donaldson, JK Rowling, Roald Dahl and Jeff Kinney.

As one of Itchy Coo’s founders as well as an editor and contributing author, I am of course pleased by the continuing success of the project. Not only has it put thousands of braw books into the hands of bairns, their families and their teachers, it has also challenged some deep-rooted negative perceptions of Scots, both within the education system and more generally across society.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis does not mean that the negativity − equating Scots with ‘slang’ or ‘bad English’, for example, or the vilification of individual writers or performers simply for using Scots − has entirely disappeared; nor does it mean that the loss of Scots vocabulary and idiom has not been substantial in many areas. Nevertheless, there are reasons to be hopeful.

First, Scots is now widely accepted in Scottish schools, especially at primary level. This is a massive change from the experience of previous generations, who were ridiculed, written off and physically punished for using their first language in the classroom.

Nowadays, children are encouraged to read, write and recite in Scots, and quite apart from the pleasure they get from this − surely a key element in successful education − it has also given many reluctant learners the confidence to participate in class as well as improve their literacy competence.

Second, there has been a shift in official attitudes. The Scottish Government, Creative Scotland, Education Scotland and other public bodies have all developed Scots language policies, some it must be said with more enthusiasm and commitment than others.

In 2015 the Scottish Qualifications Agency developed the first-ever accredited, formally recognised Scots Language Awards, and in the same year the National Library of Scotland established and funded the post of Scots Scriever.

At Holyrood, MSPs often take the oath of allegiance in Scots or their own dialect of it. As with Gaelic, there is cross-party support for recognising both the historical and continuing significance of the Scots language to the nation.

Third, there has been a growing ownership of and pride in Scots among the substantial section of the population whose first language it is, whether they are Doric speakers, Shetlanders, Fifers or Glaswegians, and whether they use it some, most or all of the time.

In the 2011 Census, questions about people’s use of Scots were asked for the first time ever (questions about Gaelic were first asked in 1881). The results were remarkable, especially given that there is some confusion as to what constitutes Scots − speakers of the north-eastern variety, for example, often consider themselves speakers of Doric, not of Scots.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSome 1.5 million respondents, or 30 per cent of the population, said they could speak Scots, and 1.9 million said they could read, write, speak or understand it. It will be interesting to see whether these statistics have risen, declined or remained stable in the last ten years.

Legally, however, Scots does not enjoy the same status as Gaelic. In 2001, the UK Government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect of both languages, but under part three of the charter for Gaelic and only under part two for Scots. The latter is predominantly a statement of objectives and principles, without explicit requirement for action, and this remains the case, although a Scottish Languages Bill, currently in its early stages at Holyrood, may alter that.

Yet even in the field of law things are changing. On at least three occasions in the 1990s and early 2000s sheriffs threatened those appearing before them with − ironically − contempt if they used the word ‘aye’ rather than ‘yes’ for the affirmative.

That stance would be difficult to sustain in today’s world. By contrast, earlier this year the Scottish Government unveiled its plans for a service to support children who are victims or witnesses of crime or who have committed offences. Modelled on the Scandinavian barnahus, the proposed service is to be called Bairns’ Hoose, a name which seems entirely appropriate but which I doubt would have been given serious consideration 20 years ago.

In countries around the globe, it is perfectly normal for people to be fluent in two or three languages, and these will usually include a ‘home’ language, a commonly used second language and a lingua franca, typically English.

Scots could and should sit comfortably in such an arrangement here, but this requires a major rethink about how as a society we enable and value language-learning in the widest sense.

Language is one of the fundamental signatures of both individual and societal identity. It is how we articulate our experience of the world and communicate that experience to others.

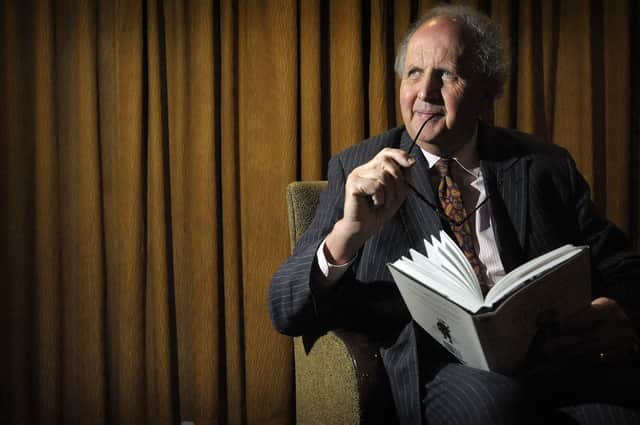

In 2010, Alexander McCall Smith, in the introduction to his story Precious and the Puggies, which he wrote specially for Itchy Coo, made this wise comment: “Every language has something to offer − a way of looking at the world, a story to tell about a particular group of people, a stock of poetry and song. The disappearance of a language is like the silencing of some lovely bird.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe whole of humanity is diminished when a language dies, and we are not made more tolerant, open-minded, enquiring or adventurous by being monoglots.

Scots and Gaelic are Scotland’s responsibility and deserve, like our wildcats and crossbills, to be protected, encouraged and celebrated.

James Robertson is a writer, editor and translator. His latest novel, News of the Dead, recently won the 2022 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. For more information on Itchy Coo, visit www.itchy-coo.com

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.