Scotland: The Global History. Scots created an international brand over the centuries but slavery casts a shadow – Professor Murray Pittock

Scotland: The Global History, published later this month, is a different kind of book. It addresses Scottish roles in overseas markets, merchant communities abroad, intellectual exports and discussions over evolving territorial and marine concepts of national and international sovereignty, as well as in charitable and convivial associations worldwide.

It acknowledges overseas influence on Scotland, and Scottish roles in the slave and other exploitative trade and in piracy. It deals with Continental Europe, the British Empire and other parts of the world, and it makes clear why and where Scottish history is distinct from the history of Britain. Structured under three main themes, Sovereignty, Empire and Finding a Role, The Global History comprehensively examines Scotland in the world and the world in Scotland since 1603.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI wrote this book for many reasons. Here are two: Scotland is a country with a demonstrable global brand and reach, and with extraordinary impact on the world, an impact and a brand largely formed in the years from 1746 to 1914, the most successful era of the Union.

At the same time, much of the present constitutional debate – though by no means all – revolves round narrowly self-regarding questions of what Scotland is, was or should be as a country, when Scotland’s distinctiveness has always been intimately connected with wider horizons than its own. Lack of understanding of our history in its global context is endemic, from school to society. To know your history is to know yourself, to know the past is to understand what is possible for the future.

Scottish society has been historically distinctive in many ways. One of these is networking. We know this, but we do not always know how. The Global History seeks to explain the influence of associational, kin and regional networks operating in a matrix with strong school, university, mercantile and professional provision, which allowed Scottish capital and innovation to spread across the world.

To take one example, it was common for laboratory assistants at Scottish universities to be put to work on small practical research projects which would enhance steam technology, and these were shared with shipyards and students in a virtuous circle between business, industry, research and education.

Likewise, the close alignment between practical botany and medical education created networks which supported Scottish initiation and leadership of medical and environmental policy in plantings and forestry from the Caribbean to New Zealand.

It was usually – but by no means always – an educated and well-connected elite who enjoyed the greatest benefits of this.

Here are two relevant careers to serve as examples. Sir Thomas Sutherland (1834-1922) was the son of a housepainter who won through to higher education at Marischal, Aberdeen’s second university which merged with King’s in 1860, an opportunity he would not have enjoyed in England or most of Continental Europe.

Sutherland joined P&O (itself a Scottish dominated business) as a clerk, and then ran the P&O business in Hong Kong, where he founded what is now HSBC to finance the development of the China trade with the US and Europe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 1872, he became managing director then chair of P&O where he used his friendship with Greenock shipbuilder John Caird to order 80 steamers between 1870 and 1914; in 1900, half of the P&O fleet was registered at Greenock.

For 16 of these years (1884-1900), Sutherland was Liberal MP for Greenock, and thus his home constituency did excellent business. Personal, commercial and political networks intersected, and British power was used to sustain Scottish success.

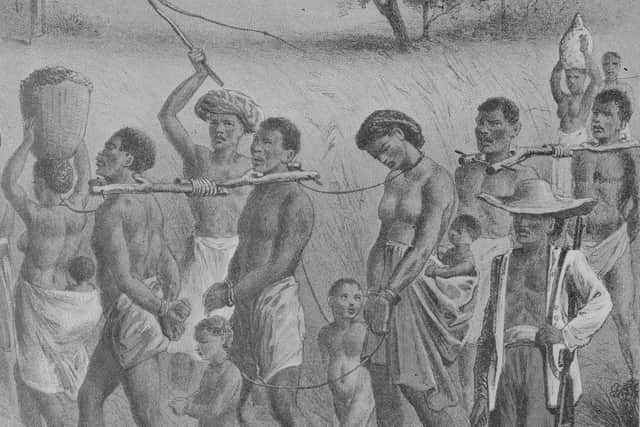

In 1748, a Scots-dominated consortium acquired a slaving outpost on the six-hectare Bance Island, 25km upstream from the mouth of the Sierra Leone river. Following the collapse of the Royal Africa Company, the African Trade Act of 1750 opened up trade to private citizens more effectively than before, and the Bance Island acquisition was thus well-timed.

The partners included the well-connected Sir Alexander Grant (1705-82) who was a kinsman of Sir Archibald Grant of Monymusk and, helpfully, a friend of fellow Scot Robert Dinwoodie, the lieutenant-governor of Virginia, the Duke of Argyll, and the houses of Erskine, Findlater and Hopetoun.

Caithness man Richard Oswald’s brothers were “eminent merchants” in Glasgow, importing 135 tonnes of tobacco every year by the 1730s. As a young businessman with their firm, Oswald’s doctor was the same Sir Alexander Grant, and Oswald met his wife at Grant’s house.

Mary Ramsay was herself already a rich woman and the trustees of her tocher (dowry) were two more Scots, John Mill and Robert Scott. Scott was a childhood friend of the merchant James Murray and when Scott became a business partner of Oswald’s, Oswald carried Murray’s shipments to Scotland on commission. On Bance Island, Scots played golf by the slaving fort with African caddies dressed in tartan, and a workforce many of whom were close relatives of the consortium partners.

Slavery was not the only business of the consortium. In the global war of 1756-63, Grant had the contract to supply British Canada with bread, beer, rum, meat, meal and dairy.

Oswald had trading links in Amsterdam, Antigua, Kolkata, Florida, Georgia, Grenada, Hamburg, Le Havre, Livorno, Nantes, Paris, Rotterdam, Rouen and Stralsund, combining Scottish continental and British imperial networks.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the final negotiations with the new United States, he was the chief British negotiator. Benjamin Franklin thought Oswald a "truly Good Man”. We may differ. It was a Scottish slaver who agreed the terms of American liberty.

Professor Murray Pittock’s book Scotland: The Global History, is published on July 26 by Yale University Press. It will be featured during an event, chaired by Ruth Wishart, at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on August 17.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.