Science and belief are not exclusive

Dispassionate readers, who have studied the Galileo caricature of a war between science and religion will know that, for almost two thousand years either side of that sorry, somewhat isolated affair, the Catholic Church and the science lab have been conjoined twins in the advancement of knowledge.

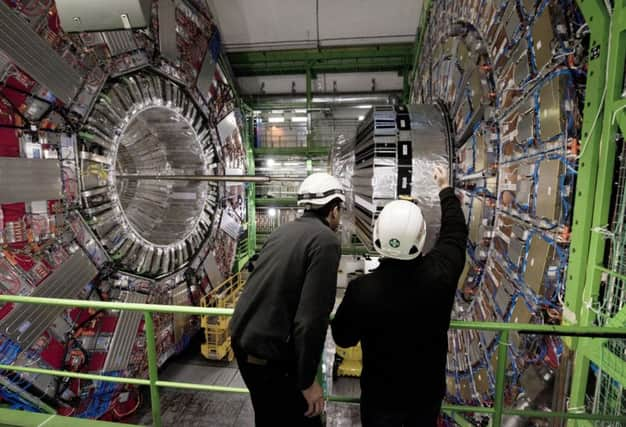

On Easter Sunday morning this year, as Christians gathered to celebrate the Resurrection of Jesus from the dead, scientists deep underground at Cern were also gathering excitedly to switch on the Large Hadron Collider for the first time since it had been temporarily shut down.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBefore giving up the ghost, the collider had already accomplished its mission of discovering what we speak of so easily as the “God Particle”. Despite the exhausting efforts of earnest campaigners against it, the desire on all sides to intertwine science and religion is as alive and well as ever.

You only need to recall how John begins his Gospel. Thinking of the very first verse of the Bible he proclaims: “In the beginning was the Word”, or Logos in the original Greek. We all know that Logos means Reason, the very source of the Greek philosophy of his time and of the method of modern empirical science subsequently.

With this verse, John pronounced definitively on the Bible’s conception of God in favour of a God who, being Truth, acts with respect for the premises of reason. Soon after, we find Christians heartily mocking other irrational gods of the time which, being so hopelessly capricious, are to them, no more than the work of human hands or, as we would say, the figment of men’s imaginations.

That is not to say there have not been wobbles in the partnership between science and religion.

The medieval Scottish Catholic scholar, John Duns Scotus, challenged Thomas Aquinas’ embrace of Aristotelian empiricism and reason, and inclined, rather, towards a God who was so sovereign that He was entitled to behave as irrationally as He pleased.

The Reformers, in their turn, sought to purify the act of religion by an appeal to faith alone, sola fides, in the assurance that faith was somehow better, more spiritual and pure when uncoupled from the limits and demands of rational investigation. Freed from the impurity of philosophy and science, religion would at last lead men to salvation.

No wonder men of science, feeling quite understandably scorned by such tendencies, would construct their own path to progress, in competition with the path of faith, and invite the masses to follow them as dogmatically as any priest ever had.

Our own age, heir to these entrenched positions, has felt compelled to make a choice between science or religion, presuming that aligning ourselves with one entails rejecting the other. It need not.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn order to foster anew the natural complementarity of science and religion, Pope John Paul II came up with the colourful image of a bird seeking to soar into the skies. He began his encyclical, Fides et Ratio, with the vivid words: “Faith and reason are like two wings by which the human spirit ascends to the contemplation of the truth.”

Flying needs two wings, just as finding the really important truths of existence needs both faith and science working somehow in harmony.

The criticism of science counterbalances religion’s all too easy temptation to fall into credulity, as if nothing could happen just by chance and even the most absurd bad luck is somehow all “meant”, by God. Faith, on the other hand, saves reason from futility. For, in a world without some transcendent Truth and Good, where everything is just chance, how can any small part of it have any meaning at all?

If you and I are really just stardust then how can this dust have inalienable rights; how can our loves be anything more than a mere collision of matter: how can our striving for justice for the weak be any more right than a totalitarian state’s will to absolute power? It was Leon Lederman who first coined the phrase “The God Particle” and in the book of the same name he parodies the Genesis story of the Tower of Babel where no-one understood another’s language or method and everything had become confused.

Into this contention the Lord said: “Let us go down again and give them the God Particle so that they may see how beautiful is the universe I have made.”’

It might not be the Very New Testament Lederman claimed it to be but it does offer a taster of a new, more hopeful, chapter in the long history of the Book of Science and Religion.

• Bishop John Keenan is Bishop of the Diocese of Paisley www.bcos.org.uk

SEE ALSO