Royal Covid train: Row over Prince William and Kate's journey raises questions over monarchy's role during pandemic – Martyn McLaughlin

He’s been an occasional contact for a few years now, and though we’ve yet to meet in person, he fully inhabits the hard-headed persona of his trade’s halcyon years. Gruff, curt, and possessed of an inexhaustible collection of swear words as part of his vocabulary, all that is missing is the pork pie hat.

Yet it was during this call, before we got down to chatting proper, that something unexpected revealed itself through the idle small talk which cut through his various affectations. “How are the Queen and the Royal family doing?” he asked. Come again? “How are they holding up through all this, it must be hard for them, right?” I wasn’t sure how best to answer. Not because I had absolutely no idea, but because it would never have occurred to me to pose the question.

Royal relatives

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe casual enquiry was a reminder of how differently the British monarchy is viewed from afar than it is at home. In many countries, and the US is a better example than many, it goes beyond mere veneration for the institution of the monarchy. There is a genuine belief that the royals are part of the fabric of our everyday life, and that the members of its family are essentially extended relatives all of our own.

There was a time when, for the overwhelming majority of the country, that was partly true. That bond, or at least the perception of it, was keenly felt, and no more so in times of strife. It is in times of crisis that the role of the royal family has tended to become clearer, when its protagonists fulfil the simple purpose of reassurance and encouragement.

But over the course of the past nine months, that implicit contract between the monarchy and the people has felt strained, and its power and profile diminished. It has drawn its ever-renewing strength from the idea that it is uniquely placed to galvanise the nation through torrid times. Yet throughout the coronavirus pandemic it has failed to do anything of the sort.

Of course, there are plenty of people able to shoulder their burdens without the monarchy’s helping hand. Equally, it would be careless to so easily dismiss the solace the Queen and her family offer to those who are older and living alone.

Queen’s Covid message

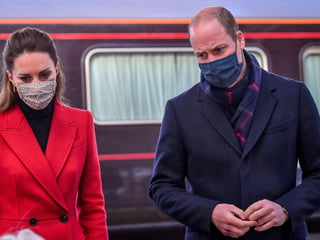

That makes their absence all the more striking, and it is why the three-day train tour by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge seems incongruous in so many ways. Yes, there is some merit in the minor political stooshie surrounding their travel at a time when vast swathes of the country remain under extensive restrictions, particularly after the justified criticism of Prince Charles travelling to Birkhall in March, despite the fact he was displaying mild symptoms of what would later be confirmed as a positive Covid-19 diagnosis.

The most jarring thing about it, however, was not the idea of rules being flouted, or familiar grievances about “one rule for them and another for the rest of us”. It was something simpler and subtler: a sense of an institution overreaching after an extended period of dormancy.

In the first week of April, the Queen delivered a televised message from Windsor Castle, in what was only the fifth time she has made a special address to the nation apart from her traditional Christmas broadcast.

The four-minute address expressed hope for the future, gratitude for NHS and care workers, and recognition that the pandemic had brought about “enormous changes” to the daily lives of everyone. It hit all the right notes and struck an apposite tone.

‘Daylight upon magic’

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdYet six months would pass before she carried out her first public engagement during the pandemic, during which time the rest of her family remained largely out of sight. Whatever occasional forays were made into the spotlight – such as Charles recording a series of video messages, his smartphone perched on a pile of books – were seized upon by those who yearn to project a modern, informal monarchy.

These occasions were embraced as evidence of a new-found relatability, without any real understanding of what such a thing means, or why it matters.

It is not unreasonable to express some sympathy with the phalanx of private secretaries, aides, and communication directors who swirl around the monarchy’s nucleus. Their task – their only real task – is to deliver the royals to the public. The pandemic has upended customs and rules that have been in place for decades, necessitating a shift online.

Never has it been so important for the royals to dismiss as an anachronism the old warning, first uttered by Walter Bagehot, that they “must not let in daylight upon magic”. But since the spring, they have remained largely in the shadows, and the backlash in recent days to the royal tour indicates that they have not yet grasped the public mood, at least in Scotland.

Throughout her reign, the Queen has understood better than most that the durability of the institution she presides over stems from what it is visibly seen to do.

“I have to be seen to be believed,” she once famously remarked. What will the response be when, in months and years to come, the question is asked of how the monarchy helped the nation through the gravest crisis in its modern peacetime history? For its ardent supporters, the answer will be disappointing, and not a little concerning.

A message from the editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.