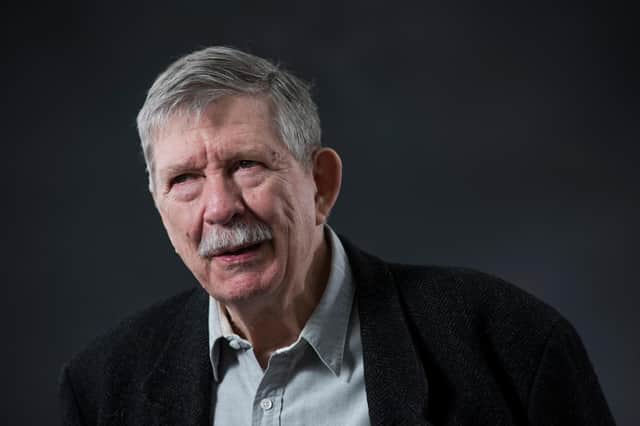

RIP Jim Haynes, the man who brought the Swinging Sixties to life in Edinburgh – Aidan Smith

Billy Connolly’s famous sketch, Shouting at Wildebeest, has lions on the prowl on the Serengeti. They’ve been playing cards, they’ve been smoking – languidly arrogant behaviour befitting their status at the top of the food chain – and now they fancy a spot of lunch. They circle their prey by stealth with slow shoulder-rolls – what magnificently malevolent beasts they are. Then the pride’s leader whispers an order to the second-in-command: “Agnes … ”

The name is funny because it’s not the one we expect to hear at that moment, Connolly having chosen it for precisely this reason. Note that he didn’t opt for Senga, which is Scottish, Agnes spelled backwards and might be considered an even funnier name. There was, though, no need for him to overdo the gag. Agnes was just right because it sounded so wrong. But maybe, when considering the role played by a woman called Agnes Cooper in the cultural life of Scotland, we think: “Ah yes, spot-on … ”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdProvocateur and hep cat

It was early 1961 when this Agnes walked into an Edinburgh bookshop and requested a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Handed the torrid tome, she opted to socially distance herself from it with the aid of a pair of coal tongs. Outside the shop she then set it ablaze.

The shop’s proprietor had already hit the phone. Not to call the fire brigade but a photographer friend whose images of Agnes’s protest went round the world. This retired missionary may have disposed of at least one copy of what she called “this iniquitous document”, but in so doing she made the name of Jim Haynes, the countercultural impresario, provocateur and hep cat.

Was he, as the Sixties started the swing, the grooviest man in Scotland? Older readers will have to confirm but it sounds like he was from the testimonials following his death the other day.

To be fair, Haynes seemed well on the way to creating his own legend before the book-burning. The Paperback Bookshop at 22A Charles Street had opened two years previously and quickly become the epicentre of as much young radical thinking as douce old Edinburgh would permit.

A native of Louisiana, Haynes had pitched up in Scotland in 1956 to continue his national service at an airbase in Kirknewton, only to fall in love with the capital and its Festival. He gained early release from the military and persuaded the owner of the shop – bric-a-brac at that point – to sell it to him on the spot. The Paperback, as it became known, was the first in Europe to deal exclusively in the soft-backed books where exciting and dangerous words hopefully lurked.

A place of pilgrimage

You went to the Paperback to hang out, drink free coffee, debate ideas and be part of a scene that didn’t yet quite know what it was. None of this went on in any other city bookshop. Haynes didn’t even use a till – there’s revolutionary for you.

Then there was the under-the-counterculture aspect to the Paperback, the books Haynes didn’t display but which you had to summon up the courage to request. He sold the ramblings of Jack Kerouac and the Beat poets; titles only otherwise found in gloriously decadent Paris; the erotic and the avant-garde; Henry Miller, William Burroughs and the Scottish enfant terrible Alexander Trocchi; the Olympia Press imprint, invariably sensational.

As the painter Sandy Moffat told Angela Bartie for her excellent history The Edinburgh Festivals: Culture and Society in Post-war Britain: “If you wanted to get books by these writers you were discovering and had never heard of before, you were going to make your way to the Paperback… Jim Haynes was always there, this guru… you felt, well, this is the kind of education that you needed.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWith no Amazon, no van drivers rushing to your front door having peed in a bottle to speed your delivery, you journeyed to Haynes’ emporium and, for many of like mind all over Britain, this was a pilgrimage. The shop became an institution, which is a very stuffy word for a place which was anything but.

An accidental stabbing

A recap: we’re talking Edinburgh, prim and perjink, where John Knox was long dead but his spirit survived, where a certain section of the populace – Morningside – deemed sex to be purely how coal was delivered. Oh, to have been a young man in the city at that time, snug in a corner of the Paperback, peepers on stalks when Henry Miller’s Sexus fell open at the dirtiest bits.

Oh to have been in the Paperback during Agnes Cooper’s visit. In one of the photos taken that day, as she brandishes her coal tongs, possibly indicating she was a Morningside resident, a student in duffle-coat and varsity scarf carries on reading his chosen shocker. He seems to be waiting for his hair to grow past his collar, for the Beatles’ first LP, for the decade to explode, and the shop was the perfect place to do this.

Haynes would go on to stage Fringe shows, organise happenings and co-found the Traverse Theatre where in 1963 – the year, according to Philip Larkin, when sex began – an actress in a Jean-Paul Sartre play was accidentally stabbed.

While doctors tended to her after the audience realised this hadn’t been part of the action, another mover and groover from that time, publisher John Calder, rushed upstairs to phone the papers, similar to what Haynes had done over Lady Chatterley. These guys didn’t need expensive PRs to show them how to seize the moment.

Haynes would go on to radicalise London, bringing it up to speed with Swingin’ Edinburgh, which owes him a huge debt. And Agnes Cooper too, for igniting the flame.

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.