Remembering Isobel Gunn, the 19th-century Scottish woman who disguised herself as a man to work for the Hudson's Bay Company – Martyn McLaughlin

He answered it to find a Scottish labourer by the name of John Fubbister, a tireless worker whose diligence and punctuality had impressed his new bosses. Since emigrating from Orkney the previous year, Fubbister had toiled dutifully alongside his crew, gathering wood, furs, and castoreum, an extract from beavers’ scent glands used as painkillers.

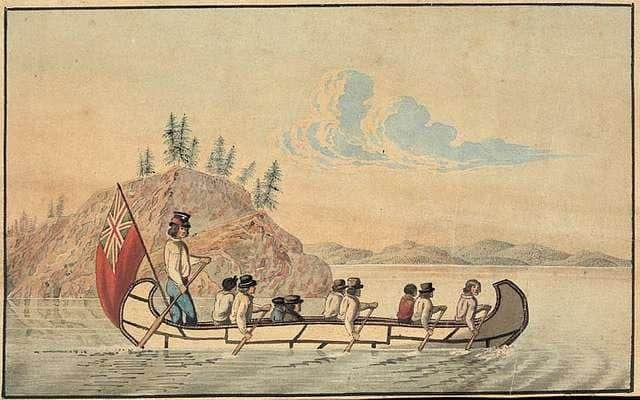

Only a few months previously, he had taken part in a gruelling 1,800-mile canoe trek, helping to ship goods to the company’s posts. Such back-breaking physical labour took its toll, yet it also brought rewards. Fubbister was awarded a pay rise, and went on to lead his own brigade of men.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut that day in 1806, his appetite for work was diminished, and he was visibly distressed and wincing in pain. Henry ushered Fubbister indoors, and let him rest a while by his fire. The entry Henry later wrote in his diary offers a compelling account of what happened next.

“I was surprised at the fellow's demand; however, I told him to sit down and warm himself,” he wrote. “I returned to my own room, where I had not been long before he sent one of my people, requesting the favour of speaking with me. Accordingly I stepped down to him, and was much surprised to find him extended on the hearth, uttering dreadful lamentations. He stretched out his hands toward me, and in piteous tones begged me to be kind to a poor, helpless, abandoned wretch.”

At that moment, as Fubbister desperately appealed for help, he unbuttoned his shirt to reveal his secret. Beneath it was a swollen stomach, almost perfectly round. Soon afterwards, by the warm hearth, with Henry and his colleagues helping, Fubbister – whose real name was Isobel Gunn – gave birth to a healthy baby boy. She named him James.

Hers is a remarkable story, which I first read about a few years ago thanks to my colleague, Alison Campsie, a skilled chronicler of Scotland’s heritage. It has been commemorated and reinterpreted over the years, thanks to a historical novel by Audrey Thomas, a documentary film by Anne Wheeler, and a poem by Stephen Scobie.

In Canada, Gunn has been rediscovered and lauded as one of the nation’s heroines. But in Scotland, the story of how she lived and worked cheek by jowl with a crew of hardy men remains relatively obscure – a fact that has long perplexed me.

Fubbister, of course, was a pseudonym. Or rather, it was the name of Gunn’s father. She had been born and raised in Tankerness, although little is known about her life until she reached the age of 26. It was then that she took the decision to board the Prince of Wales ship at Stromness, its decks teeming with fellow emigrants, as well as chickens and geese.

By then, Gunn had already convinced Hudson’s Bay recruiters that she was a man, and she set sail in her disguise. To this day, no one knows why she did so. Research by Thomas suggests that Gunn’s brother, George, had worked in the Canadian wilderness, and that his tales of derring-do had inspired her to follow in his footsteps. Other theories abound that she set foot on the Prince of Wales in order to pursue a man she loved.

They are plausible explanations, but I like to think the young Orcadian woman acted out of more rational motivations. At the time, Hudson’s Bay offered her a contract worth £8 a year. Such opportunities were out of reach for women in her homeland and, knowing full well that Hudson’s Bay did not employ European women on account of the nature of the work and societal gender expectations, perhaps she decided to take the only option open to her.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEither way, the fact that she was able to keep her cover for quite so long – right up until the point she went into labour – is astonishing. She was able to bond and socialise with her gnarled colleagues, and above all, work as hard them despite the fact she was pregnant. One worker, Hugh Heney, later praised her industry, commenting on how she “worked at anything and well like the rest of the men”.

Sadly, the discovery of Gunn’s secret meant she was denied the opportunities she so bravely sought out, and her story is tinged with sadness and, some suspect, violence. One veteran settler later claimed that Gunn became pregnant after she was raped. As word got out about her real identity, she was reduced to working as a washerwoman in Martin Falls in northern Ontario. It was deemed appropriate work for a woman, but Gunn, as had become clear, was no ordinary woman.

After having her son baptised, she eventually left the employment of Hudson’s Bay, and in the late summer of 1809, boarded the Prince of Wales back to Orkney. She would remain there for the rest of her life, raising James as best as she could, but one can only imagine the welcome she encountered.

Even if news of her exploits had not crossed the Atlantic, her return with a child born out of wedlock would have been sufficient to inflict further suffering. All that is known of the second act of Gunn’s life is that it was a long one. She worked as a stocking knitter in Stromness, and lived until the age of 81.

I hope she had a happy life, though that is wishful thinking. It is scant consolation to Gunn, but more than two centuries on, the fact that her story is still being told is a victory of sorts. On the anniversary of wee James’s birth, let’s all raise a glass to his mother – a forgotten Scottish pioneer.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.