Read all about it: Breaking news in 1721 - Susan Morrison

We don’t know just how big that mob was, but hangings like this were usually a huge draw. However, we do know what he said. He had a score to settle and he made sure he was heard.

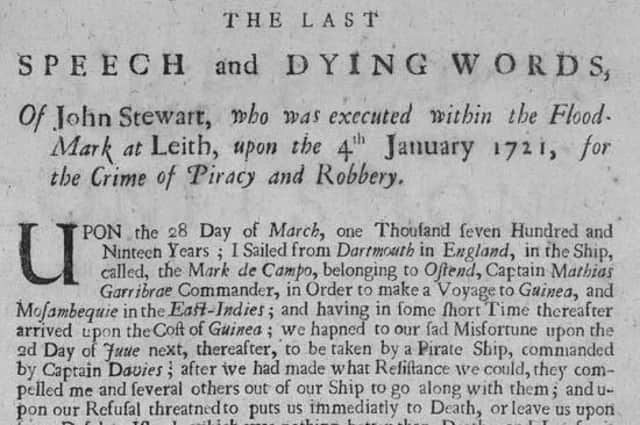

He didn’t deserve this terrible fate on that cold Scottish day, he declared. No career pirate he, for as he says in his own words, the pirates who swarmed about his ship off the coast of Guinea “compelled me and several others out of our Ship to go along with them; and upon our Refusal threatened to puts us immediatley to Death, or leave us upon some Desolate Island, which was nothing better than Death “

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdJohn claimed to be a ‘forced man’, threatened with a terrible fate if he didn’t join the pirate crew.

His protests of innocence were ignored, but at least his last words were recorded, along with documentary evidence that pirates really did leave unlucky souls on desert islands, or at least threatened to.

And we know what he said, because we can read them. On John Stewart's last day someone would have stationed himself as close to the condemned man as he could get to scribble down those precious words. He might already have the details. He may have slipped the jailers a penny or two and got access to John prior to execution, but what if the lad let slip a juicy last-minute admission? And anyway, you wanted an account of the doings on the scaffold.

Not easy. A hanging draws a big crowd, a pirate hanging even more. Drink will have been taken by everyone from the hangman down, so trouble was common.

And you can forget biros, pencils and fancy gadgets to record. You’ve got quill pens, liquid ink and fairly rubbish paper. Time is of the essence. Your man on the spot has to get the details and only has one chance to do it above the din of the mob around you. You can hardly shout ‘Can I just check the name of that ship?’ when your interviewee is now unlikely to sue in the event of being misquoted.

Catching the last words of a condemned man was a tricky business, but a profitable one. The last words of John Stewart were bought and printed by Robert Brown in Forrester's-Wynd, and then sold as a broadside, the news outlet for the masses for nearly 300 years.

The broadside was, as the name suggests, big. The size of an old-fashioned broadsheet newspaper unfolded. Just like today’s press, they covered murder, scandal, riots and mutinies, as well as a fair amount of ballads and ghost stories. Crucially, they were printed on only one side, so that they could be stuck on the walls of a tavern, and then everyone could read them.

A good landlord or landlady would have the latest editions to hand, but always made room for old favourites, like the lyrics of a good ballad. You can imagine that on a rowdy evening in the pub, someone might be prevailed upon to read the broadsides aloud for the assembled company, a sort of mildly tipsy spur-of-the-moment Huw Edwards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs with modern media, the broadside could carry a political agenda. It won’t surprise Scots to find pro-Independence ballads sniping at the union. There were anti-slavery sentiments in ‘The Slave’s Dream’ , and there are several existing broadsides lamenting the fate of two of the Radical Weavers of 1820, Hardie and Baird.

Most spectacularly, and further afield, the broadside carried the American Declaration of Independence throughout the rising colonies of the future United States. For some, this would have been the first news of the break with George III and the beginning of the War. Bet that stopped the singing in the pub for a minute.

Not all the news was reliable, of course. An astonishing amount of nonsense was churned out by the broadside writers. A baby was born in Edinburgh, they claimed, that was able to speak English ten minutes after it was born and a mermaid had a chat with a chap in Cromarty.

Once the latest reports of murder, war and marvels had been read and considered, it was time for a song from one of the new ballad broadsides, especially if a fiddler had dropped by to accompany the singing.

It's a bit like Channel 4’s Krishnan Guru-Murthy suddenly breaking off from the latest hot drama at Number 10 to lead the viewers in a quick chorus of ‘A Cronie of Mine’, the first verse of which ends with the lines “There's ane, an auld blacksmith, wi' Janet his wife, / And a queerer old cock ye ne'er seen in yer life’.

The broadsides carried the word out to the people until the rise of mechanised printing in the early 19th century. This, and the gradual lifting of tax on newsprint, led to the rise of the mass newspaper. Cheap magazines such as Household Words, edited and written by no less than Charles Dickens, were available. Everyone wanted the next chapter of the latest serialised novel to read at home.

The National Library of Scotland has a wonderful digital resource where you can start looking at the broadsides of the past. Search for NLS, ‘Word on the Street’ and you, too, can learn the words of a scurrilous ballad, find out about the king's departure from Queensferry back to England and an account of a terrible trial in Glasgow for murder.

Pretty much like any newspaper today, really, but without the singing.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.