Peter Jones: Nats are playing a game of bluff

In just two simple moves, the SNP has exposed the gross hypocrisy on which its campaign for independence, and its lesser cousin – full fiscal responsibility – is based. If anyone needed any evidence that the claim that independence would lead to a more prosperous Scotland was false, the SNP have just provided it.

An end to austerity can only be provided by a UK government, as John Swinney was pleading with George Osborne to do yesterday, for the shelving by Nationalist MPs of demands for full fiscal responsibility also shows it cannot be done by Scotland outside either the current fiscal or political union.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdLooking at recent events, I was reminded of a rueful story often told by a very eminent Canadian (he would say Quebecois) economist. Francois Vaillancourt is a professor of economics at Montreal University. One of his special interests is in the financial and economic relationships between different levels of government in the same country.

He is thus an expert in fiscal decentralisation, how tax devolution works and what the economic effects are. As such he has been widely consulted by many governments and such organisations as the World Bank and the OECD.

Indeed, it is to him that we owe the idea that the Scottish parliament should gain control over 10p of income tax. That was the suggestion he made when he was consulted by the Calman Commission and which is now enshrined in the Scotland Act 2012.

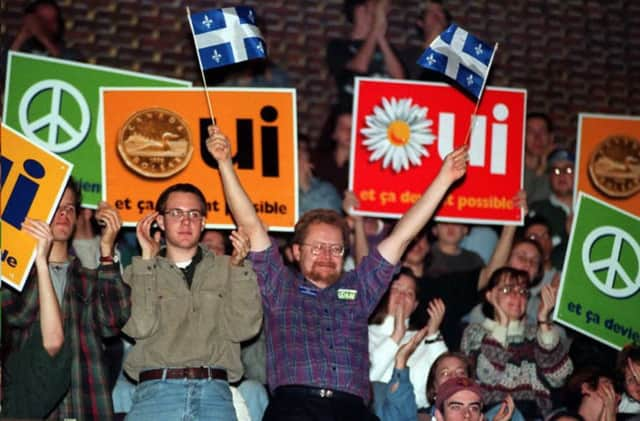

Prof Vaillancourt is also a supporter of Quebec independence, or sovereignty as they call it, and a member of the independence-seeking Parti Quebecois. The PQ was only too delighted to appoint him as an economic spokesman shortly before the 1995 referendum on Quebec independence.

I heard him recount at an economics conference in Edinburgh that the party was less pleased with his first major media interview. Could Quebec be an economically viable independent country, he was asked. Of course it could, he said. But would it be richer or poorer than it was as part of Canada. Oh, poorer in the short term, he said, adding that in the longer term it might well be richer if shrewd economic policies were pursued.

Of course, the dreadful media jumped all over his response regarding the short-term prospects, plastering it everywhere, as did the PQ’s federalist opponents. The PQ promptly sacked him.

Talking about this a decade later, he said he was just being honest about the economic prospects for Quebec independence. We would have been poorer, he said, but probably happier as an independent country.

Leaving aside the happiness factor, a somewhat debatable point given that being poorer is not usually associated with greater contentment, Prof Vaillancourt’s comments fit the Scottish independence argument perfectly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdScotland could be a viable independent country, but it would certainly start off poorer than it is as part of the UK. I am not claiming, as some of the more visceral Nationalists assert in retort, that Scotland is too poor, too wee, too stupid, to be independent, merely noting that the economic facts point towards an independent Scotland being poorer than as part of the Union.

Conveniently, the Scottish Government has done two things which say that this must be right. First, in the Westminster debates about implementing the Smith Commission proposals for Scotland to have greater tax and welfare powers, the SNP group of 56 MPs are not going to demand that the UK government grant Scotland full fiscal responsibility.

This would mean that inside the union, the Scottish Government would have to raise pretty much everything it spends, ranging from the costs of education and health to payments to the UK government for debt servicing and defence, from what Scots and the offshore oil and gas industry pay in taxes.

Unfortunately, Scotland’s tax revenue currently falls well short of public spending to a much bigger degree than does the UK when measured relative to the size of the Scottish and UK economies. The Scottish Government’s published figures show that in 2013-14, Scotland’s deficit equated to 8.1 per cent of Scottish GDP against a UK deficit of 5.6 per cent of UK GDP.

Analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), which has been disputed but not refuted by SNP ministers, is that the gap between Scotland and the UK will widen, not narrow, in the next few years. By 2019-20, the IFS reckons Scotland’s deficit will be 4.6 per cent of GDP while the UK should move into a small surplus of 0.3 per cent of GDP. The difference in cash terms in today’s prices is £8.9 billion, the amount by which tax revenues would have to rise or spending be cut, for Scotland to reach the same fiscal place as the UK.

That’s the shocking reality of what full fiscal responsibility means – spending cuts equivalent to about 80 per cent of the health budget or tax rises equivalent to about 80 per cent of what we already pay income tax.

That’s why SNP MPs will not be demanding full fiscal responsibility, because they don’t want to be responsible for forcing even worse austerity on Scots than is George Osborne. You don’t believe me? Well, ask yourself, if Scotland had a better budget balance than the UK would the SNP still refuse to argue for what half of Scotland voted for in their manifesto? Of course it wouldn’t.

The conclusion is clear – an end to austerity can only be delivered by a UK government. Whether the SNP’s plan for real-terms public spending increases of 0.5 per cent a year – what Mr Swinney sought in his meeting with Mr Osborne – actually adds up to austerity easing and within-target deficit reduction, is a debate for another day.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI’ll only note that the so-called economic analysis Mr Swinney published to substantiate his claims is only a statistical number-crunching exercise. It contains no modelling or analysis of how the proposed budgetary changes would affect the economy and tax revenues, or debt and debt servicing costs which might well rise if financial markets concluded the government was abandoning its present course of deficit reduction.

Mr Osborne may have listened politely but it is unlikely he will pay much attention, for what has also been revealed is that any threat by the SNP to take Scotland out of the Union is a bluff in which only the Scottish people would be the losers.