Obliterating our history by removing statues is path to repeating mistakes - Brian Monteith

History is a messy affair. It is complicated. There is often no settled narrative, with new emerging evidence often turning upside down the once dearly held beliefs. Rushing to make moral judgments or political decisions based upon supposed historical consensus or revisionist urban myths – rather than researching the truth – is likely to cause error if not an injustice.

Who, for instance might you have thought said the following when he found out that a friend’s son-in-law had “some Negro blood in his veins” and was running for the town council in the ward that contained the zoo?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Being in his quality as a n****r a degree closer to the animal kingdom than the rest of us, he is undoubtedly the most appropriate representative of that district”.

Might it be Henry Dundas, the first Viscount Melville and Scottish politician whose statue sits atop the Melville Column in Edinburgh’s St Andrew Square – and, it is claimed of him, opposed the abolition of slavery – so we should topple his likeness from its imperious view?

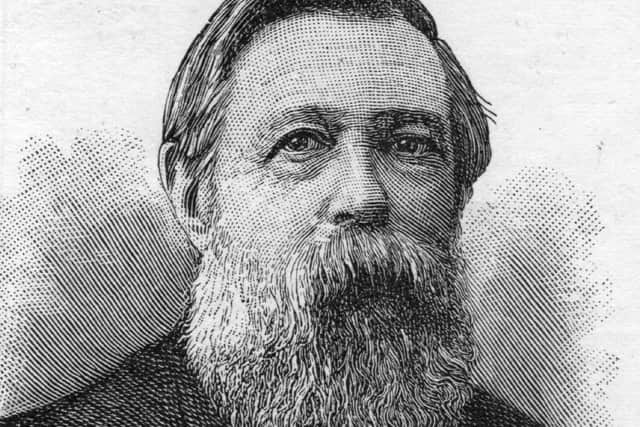

No, it was in fact Friedrich Engels, writing to the daughter of Karl Marx who was married to Paul Lafargue, the candidate for an election in Paris. If one reads of the writings of Marx and Engels, it does not take long to find evidence of what we now call racism, attacking coloured peoples referred ubiquitously as n*****s – as well as many white Europeans such as the Slavs.

Yet while Manchester continues to have a statue in memory of local factory owner Frederick Engels – without the daubing of paint or violent protests against his self-evident racist bigotry, never mind his formulation and proselytising with Karl Marx of a creed that led to the deaths of tens of millions – lists of supposed imperialist monsters are proposed advocating their commemorations be pulled down.

The history of Dundas now seems controversial, but then he lived in the late 18th and early 19th century, when few had a vote, never mind universal suffrage for all men and women that was only achieved in 1928.

It is said by his detractors he opposed the abolition of slavery, but the reverse is true. As Dundas’s biographer Michael Fry has explained, using original source material, Henry Dundas was instrumental in ending negro slavery and native serfdom in Scotland. In fact he supported its abolition across the British Empire and worked to achieve it.

In 1777 Henry Dundas was lead advocate for Joseph Knight, a negro slave brought from Jamaica to Scotland by his owner, sugar plantationist Sir John Wedderburn. Knight was seeking his freedom through an appeal in the Court of Session following earlier rulings in the county and sheriff courts. In winning the case for Knight’s emancipation, Dundas demonstrated slavery did not exist under Scots common law and that any slaves then abiding in Scotland could thus claim their freedom. For that alone I think Dundas deserves his place in St Andrew Square.

By 1792 Dundas was secretary of state in the home department in William Pitt the Younger’s government when exchanges took place around William Wilberforce’s latest attempt to abolish slavery. Dundas stated, “That the slave trade ought to be abolished, I have already declared, But I believe that any other than a gradual abolition will be attended by bad consequences…”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDundas argued that even the most outspoken enemies of slavery could not see it taking any less than five years to be made a practical reality – while opponents of Wilberforce claimed it required at least ten. Abolition did not enjoy a majority in the House of Commons but Dundas split the difference and proposed seven years and with Pitt’s support won a large majority of 230-85 in the House for abolition from January 1800.

Dundas’s gradual approach included the immediate end of British imports of slaves from foreign colonies in 1792 and no importation of new slaves by foreigners to the colonies themselves from the following year. Having won the argument and the vote, it was the House of Lords that rejected the bill and it was not until 1807 – with Dundas now in the Lords – when Wilberforce was able to achieve the abolition of slavery.

Although a Tory, Dundas was what we would today consider a centrist, a pragmatic politician or fixer who could get things done. Had the Dundas proposal been ultimately successful, slavery would have been abolished sooner than it was, that he did not countenance immediate abolition hardly makes him a racist or a supporter of slavery or even, as some claim, an obstructer of abolition.

As the first secretary of war, Dundas was of course also responsible for re-equipping the Royal Navy and making it ready to repel the French and Spanish fleets in the Napoleonic wars. It was Napoleon, we should remember, who re-introduced slavery in the French Empire after it had been abolished in the French Revolution. Debate can be had about the exact role of Dundas, but there is no doubt he was a huge political figure in his time, arguably the first truly successful British politician, rather than a purely English political figure after Union in 1707.

In comparison to the legacy of Frederick Engels the treatment of his monument, the Melville Column (1821) and statue (1828) – paid for by subscription of Royal Naval officers, petty officers, seamen and marines ten years after his death – says much of the current fashion for emoting against our historical past.

The reaction of people across the world to the appalling death of George Floyd in Minneapolis has triggered a great sense of racial injustice with a particular focus on police brutality, but care should be taken to recognise that there are always people ready to exploit political reaction for their own ends.

As a phrase #BlackLivesMatters is beyond reproach – but we should be careful to automatically transfer our concerns to any organisation simply because its name is the same as the phrase. Its support for defunding (abolishing) the police would only ensure an anarchy that would bring greater deaths of innocents. Surely all lives matter?

Much as I abhor what their writings led to I am not for pulling down the Engels statue in Manchester nor removing Karl Marx’s bust in Highgate Cemetery. Like the monument to Dundas, Peel or Gladstone they deserve their place.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdObliterating our history – good and bad – by establishing a year zero approach where everything we can learn from and debate around is removed from view is the path to having no collective memory and repeating past mistakes.

Brian Monteith is editor of ThinkScotland.org

A message from the Editor:

Thank you for reading this story on our website. While I have your attention, I also have an important request to make of you.

With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on many of our advertisers - and consequently the revenue we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you taking out a digital subscription.

Subscribe to scotsman.com and enjoy unlimited access to Scottish news and information online and on our app. With a digital subscription, you can read more than 5 articles, see fewer ads, enjoy faster load times, and get access to exclusive newsletters and content. Visit https://www.scotsman.com/subscriptions now to sign up.

Our journalism costs money and we rely on advertising, print and digital revenues to help to support them. By supporting us, we are able to support you in providing trusted, fact-checked content for this website.

Joy Yates

Editorial Director

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.