Nicola Sturgeon, a champion of social democracy, could have led Scotland to become one of the world's happiest nations – Joyce McMillan

Perhaps not surprisingly, five of the top seven places were taken by the Nordic social democracies, Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Sweden and Norway; the UK, by contrast, ran in at number 19. All of which points – and has pointed for years – to the fairly unambiguous conclusion that if they are looking for a social and economic system that delivers the best human outcomes, then the world’s leaders should be seeking to emulate those Nordic social, political and economic systems as closely as possible.

The fact that so many of them do not is a tribute to the recent historic success of the political right, and its wealthy backers, in persuading people to vote against their own best interests. Yet still, a functioning, climate-literate 21st-century social democracy remains a cause worth fighting for, and one that – by many different names – has been close to the hearts of Scottish voters for the last 60 years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

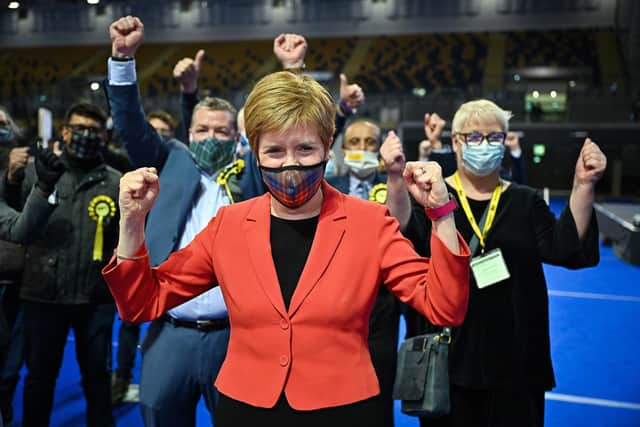

Hide AdThose seeking an insight into Nicola Sturgeon’s huge electoral success in Scotland, as she steps down as First Minister, therefore need look very little further than that quest for a 21st-century social democracy, and her relationship with it. First drawn into politics by her loathing of Thatcherism, and all it meant for communities across Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon was for most SNP voters simply a leader who – in a time of increasingly toxic and irrational right-wing leadership, both across the globe and in Brexit-riven Britain – talked highly articulate social-democratic sense about the challenges facing Scotland and the world this century, and who sought alliances with other social democratic leaders from New Zealand to Iceland, in developing that world-view.

Nor – as some critics like to imply – was Nicola Sturgeon’s commitment to those values all talk and no action. There were very serious policy failures, too numerous to list here. Yet those now dismissing Nicola Sturgeon’s First Ministership as an outright failure would do well, before they rush to judgment, to talk to those families with young children who, thanks to Scotland’s additional child payment, now find themselves almost £100 per month per child better off than parents elsewhere in the UK; or to those who have benefited from the Scottish Government’s mitigation of scandalous UK benefits policies such as the notorious “rape clause” and the bedroom tax. In the week before Nicola Sturgeon resigned, the UK Institute of Fiscal Studies noted that Scotland’s tax system was now redistributing wealth from rich to poor more effectively than anywhere in the UK over the last quarter century, an achievement of which Nicola Sturgeon can be justly proud.

Now of course, critics on both the right and the radical left will dismiss these achievements as mere details, dwarfed by much larger failures. If Scottish politics has a centre of gravity, though, it lies somewhere in the social-democratic realm where such practical policies are undertaken, sensibly and steadily, in the effort to improve the security, well-being and opportunities of ordinary citizens, and constitutional change tends to come, as it did in the 1990s, only when those policies can no longer reliably be pursued by any other means – which in the minds of increasing numbers of people, over recent years, meant at least the possibility of independence.

All of which, of course, makes the internal SNP shambles which has accompanied Nicola Sturgeon’s resignation all the more deplorable, in that it makes any sober assessment of her policies as First Minister less likely. It certainly never occurred to me, as a broad supporter of her policies, that she would turn a blind eye while her husband ran her political party in a way that seems, at best, to have been completely incompatible with her social-democratic principles; nor did her adversaries in the independence movement help their efforts to expose those apparent abuses by so often linking them to other contentious causes.

Yet with Peter Murrell’s forced resignation as SNP chief executive, it is now clear that Nicola Sturgeon bears a heavy responsibility for allowing her record as First Minister to be tainted by such an unnecessary failure of governance and ethics within her party, a responsibility that is all the heavier because the circumstances of her departure, as a prominent national and international spokeswoman for enlightened 21st-century social democracy, will inevitably damage that cause – not least within her own party, as the present scrappy and right-inflected leadership election shows.

Well, enough; in politics we are not offered perfection, but only a choice of flawed politicians who may or may not have the skill, the will and the vision genuinely to advance the interests of the ordinary citizens who vote for them. In a time of third-rate and often downright destructive politics, Nicola Sturgeon stood out, for those of us on the centre left, as a politician who did have those qualities, at least in some substantial measure. She has undoubtedly failed to live up to her principles so far as her party is concerned, in ways that may yet destroy her reputation completely.

Yet that is not, by a long way, the whole story of her leadership; and this week, as she steps down, it’s as well to remember the long period, since 2014, when she seemed to many Scots by far the best of a bad bunch, in terms of rational and compassionate leadership in troubling times, and a serious voice for a sustainable future that might one day – in a different world – have seen Scotland, too, rise to the upper reaches of the happiness index, as a nation striving towards that precious social-democratic balance between freedom and security, justice, equality and love.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.