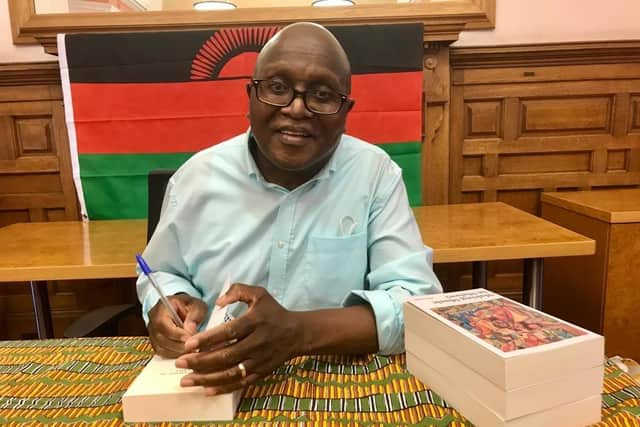

My obsession with Malawian music - Dr John Lwanda

I suppose I was born a musicophile, always the first to tap feet or indeed dance. My upbringing, perhaps, exacerbated and, in a way, consolidated this tendency. My dad, an Anglican primary school teacher taught music, Scottish Country dancing, and could sing like NP Kazembe. My mum broke into gospel or hymns at the drop of an argument. I was exposed to all sorts of African, European, and American music from the early 1950s via Radio Lusaka (CABS).

Since 1969, I have collected Malawian music on vinyl, cassette, compact discs, video and digitally and I have written about it since 1981. At some point, especially as I was driving around doing my house calls, the music consumption also became analytical. Time gave me the opportunity to listen to the lyrics and the messages they carried. My research covered traditional music, sacred and gospel music, jazz band music, popular music, mbumba music, afrojazz and classical music.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI won a locally made Nzeru radio in a writing competition in 1968 and on arrival in Glasgow in 1970 was able to buy a powerful shortwave radio from John McCormack’s (Bath St, Glasgow). They had hire purchase terms to arriving international students on scholarships. Then on shortwave I could hear some African radio stations (South Africa, Ghana; even, briefly, in the 1970s, the Malawi Broadcasting Corporation).

In the wake of the World Music interest, I run a small record company that issued a number of compilations and new recordings of Malawi music. Later, as a mature PhD student in history and social science, I recorded traditional, gospel and popular music on video. My efforts saw me meet and interact with key Malawi musicians, such as: Alan Namoko, Saleta Phiri, the Kasambwe Brothers, Kalambe, Kamwendo Band, Waliko Makhala, Overton Chimombo, Wyndham Chechamba, George Mbendera, Beatrice Kamwendo, Lucky Stars, the Malawi National Dance Troupe, and the Mount Sinai Choir.

My collections and research have produced papers in newspapers, magazines, journals, books, and encyclopaedias.

I believe that in largely oral cultures – and Malawi is one such – music plays an important role in storing, transmitting, interpreting information, history, and traditions. To understand such cultures, one needs to be able to access some of their public spheres. In Malawi, on the authority side, music is used in most traditional rituals and ceremonies; it is, as everyone familiar with Malawi knows, a major staple of political rallies. It is used in school as well as health education. Gospel is ubiquitous and pervasive.

On the other side, music is part of normal resistance to poor governance, creating beni in colonial times and featuring significantly in postcolonial popular music. Music is, of course, a major factor in surviving lives blessed with poverty and misery; humour features greatly in Malawi music. Malawians use music to deflate sectarian and political tension; the same tune can carry lyrics by opposing factions. Being oral and communal, musical lyrics in Malawi must, of necessity, be multi-layered and, if needed, ambiguous, so that both children and adults can dance communally each at their own level.

Dr John Lwanda is a medical doctor, writer, poet, researcher, social historian and music producer.

John Chipembere Lwanda’s Making Music in Malawi (2021), (451 pages) is published by Logos Open Culture, Lilongwe. A few copies are available from Pamtondo, 41 The Fairways, Bothwell, G71 8PB ([email protected]) at the discounted launch price of £25.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.