Microbes: Greater understanding of how tiny life forms work together could lead to remarkable scientific breakthroughs – Professor Nicola Stanley-Wall

They are highly diverse organisms found in almost every conceivable environment on Earth, even the most extreme. However, in most cases, single microbes are too small to be seen with the naked eye, so they are often overlooked and under-appreciated.

To shine a light on these unsung organisms, my colleagues and I at the University of Dundee have used fascinating aspects of microbial life to seize the attention of Scottish residents, including schoolchildren, to engage them in the hidden and highly dynamic world around them. We have always focussed on the beneficial impacts of microbes – for example revealing their use in food and drink production such as bread and wine, or their role in producing selected antibiotics used to treat infections like tonsillitis.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

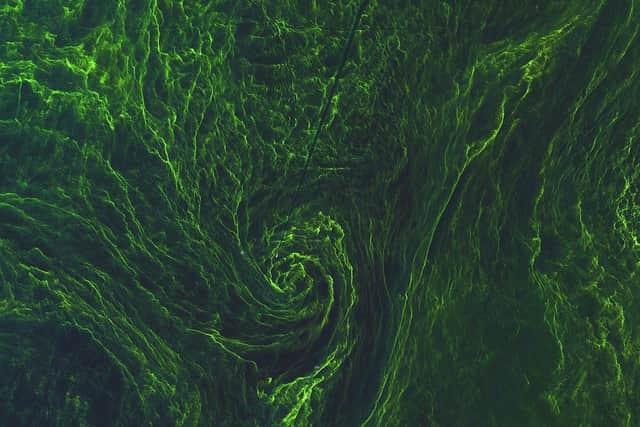

Hide AdA personal focus of mine is ‘biofilms’, which are social communities of microbes bound together in a self-produced, sticky glue called the biofilm matrix. Some widely known examples of biofilms include dental plaque, algal blooms on the surface of lakes, and the slimy mass frequently found in your shower drain.

By investigating how single bacteria coordinate their siblings within the community to form a biofilm, we now know that a community of microbes living within a biofilm possess attributes not seen in individual microbes. These properties allow microbes to do amazing things, such as making a waterproof coating for the community to protect the residents inside. Other outcomes of microbes forming biofilms include the ability to ‘bioremediate’ polluted soil (for example, removing or reducing contaminants), clean wastewater or help plants access nutrients contained in the soil.

The soil-dwelling bacterium, Bacillus subtilis, is remarkable. Its potential applications range from promoting plant growth to functioning as a probiotic that can improve human and animal gut health and helping cracks that form in concrete to heal.

Given the versatility of microbes and the persistence of biofilms in the natural environment, they offer a powerful opportunity for development and innovation, especially around sustainable food production and environmentally friendly alternatives to cleaning. The National Biofilms Innovation Centre, which I work with through my research, is a knowledge centre established to connect academic researchers and industry in the study of biofilms to create a better understanding of the science and to achieve breakthroughs.

In the coming years, I believe that novel approaches to harness the power and capabilities of biofilms will become commonplace; and if we fail to take note of biofilms, we might miss opportunities that are green, sustainable, inexpensive, and safe.

Nicola Stanley-Wall is a professor of microbiology in the School of Life Science, University of Dundee, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. This article expresses her own views. The RSE is Scotland’s National Academy, which brings great minds together to contribute to the social, cultural and economic well-being of Scotland. Find out more at rse.org.uk and @RoyalSocEd

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.