Martyn McLaughlin: Glenbuck’s legend lives on

The stretch of the A70 that winds from Douglas to Cumnock is one of Scotland’s lesser travelled roads, but the journey along it offers an instructive lesson into how identity, industry and sport can combine to forge an spellbinding legacy for a community long after its bricks and mortar have ceased to stand tall.

A few weeks ago, a writing project took me down to this forgotten nook of the Southern Uplands. Driving the 20 mile route where coalfields bind East Ayrshire to South Lanarkshire is to witness man’s restless impulse to bend nature’s form to his will. Barely a fifth of the landscape in the area is natural, the terrain having been mined by hand and machine for close to a millennia.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHalfway along the road, a turnoff leads to a single lane which skirts a mile or so north around a secluded and exposed loch. Save for the odd toll house or cottage, there is little sign of life. But by one layby, a black granite memorial speaks of an illustrious past. “Seldom in the history of sport,” the inscription begins, “can a village the size of Glenbuck have produced so many who reached the pinnacle of achievement in their chosen sport.”

For all that the current torpor of Scottish football invites its acolytes to seek escape in glory days gone by, I have always considered it remarkable how the story of Glenbuck’s prolificacy remains unknown to so many followers of the game in Scotland.

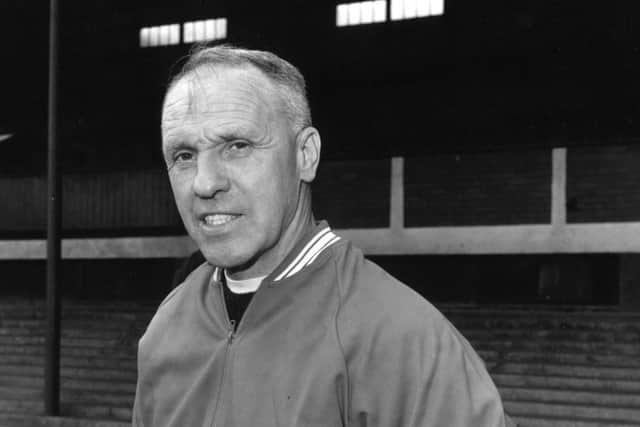

Its most famous export, of course, is Bill Shankly, a folk hero on Merseyside first, a former football manager second. But the late Liverpool great’s considerable shadow too often obscures the wider story. Thankfully, a new book on the rise and fall of Glenbuck and its footballing heroes provides a long overdue excavation of this rich seam of Scottish social and sporting history.

Shankly’s Village argues that Glenbuck is the most remarkable place in the pantheon of football. “If a sport is supposed to have a home,” suggest its authors, Adam Powley and Robert Gillan, “it might as well be here.” It is a bold yet eminently reasonable claim.

Here stood a village whose population never exceeded 1,700, but which turned out no fewer than 53 professional footballers over the course of less than four decades; the equivalent of a minor non-league club in the Greater London area producing almost a quarter of a million young men capable of making a living by putting laces to leather.

This extraordinary roster included five Scotland internationalists and four FA Cup winners. Even those sons of the fertile Ayrshire soil denied the game’s greatest prizes lined up for some famous names, such as Everton, Manchester City, Newcastle, Preston North End, Rangers and Sheffield Wednesday.

Wonderful footage exists of two Glenbuck lads, Alec Brown and Alec Tait, helping Tottenham Hotspur to victory over the then northern powerhouse of Sheffield United in the FA Cup final of 1901, all before a Crystal Palace crowd 114,815 strong, the third-largest football attendance in English history.

Before that, they cut their teeth with the Cherrypickers, the wonderfully named village team in Glenbuck that deserves an equal billing with other long-forgotten giants of the British game, such as Third Lanark, Corinthian FC and Blackburn Olympic.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdGeneration after generation took to the humble pitch of Burnside Park, a lineage which accrued at least six Cumnock Cups, three Ayrshire Junior Challenge Cups, two Ayrshire Charity Cups, and one Mauchline Cup and Ayrshire Junior Cup apiece. Anyone who has observed close up the competitive nature of the junior game in Ayrshire will know such a haul is no mean feat.

The last trophy won by the Cherrypickers came in 1931, their final year as a team. By then, Glenbuck’s population had dwindled to 551 due to the decline of the mining trade and the Great Depression. Come the early 1970s, barely 20 people remained, among them Shankly’s sister, Liz. Within a few years, all were gone. Glenbuck became a quirk of cartography, a roadsign leading the way to a village of ghosts.

These days, Burnside is an overgrown clump of grassland and weeds bordering Stottencleugh, a gurgling stream that runs a rust red due to the spoils of an opencasting regime that has transformed a once thriving community into a rubble-specked snarl of pocks and mounds.

The few documents that record what life was like here in the early 20th century describe grinding hardship. At least 12 men died underground between 1884 and 1928, succumbing to collapsed roofs, runaway haulage cars, or lift cages which plummeted to the dark of the pit bottom. In Shankly’s schooldays, most pupils relied on the National Union of Scottish Mineworkers to provide a mid-day meal of a roll and jelly.

Yet the most evocative accounts are the first-hand testimonies of the tiny band of surviving Glenbuckians, such as Tom Hazle. Now nearly 90, he offers an astute assessment of the village’s gift to the footballing world, one which refuses all notions of jumpers for goalposts style sentiment. “Mining was the thing that made the football players in Glenbuck,” he explains in Shankly’s Village. “It was the pit. We were desperate to get out of it.”

This is the brutal truth underpinning Glenbuck’s efficacy as a nursery of footballers. Life was so perilous that sport was the only realistic escape. Those of us who bemoan Scotland’s failure to recapture the grassroots footballing success of previous decades fail to properly acknowledge the influence of the gruelling social and economic circumstances in communities like Glenbuck. These places proved as ruinous as they were inspiring and whatever spirit, purpose and character was summoned came at a heavy cost, one we should never forget.

As one of Scottish football’s greatest chroniclers, Hugh McIlvanney, writes on the back cover of Shankly’s Village: “Physically, Glenbuck has been expunged but its name will always have resonance for anyone interested in the importance of football to the working-class communities of what used to be Britain’s industrial areas.”