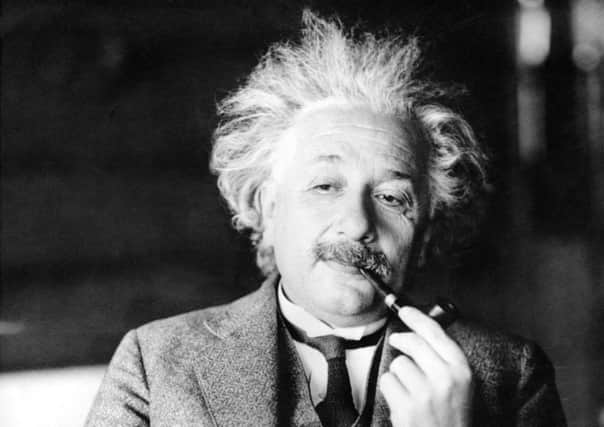

Martyn McLaughlin: Albert Einstein dared to change everything

It is a matter of some regret that the lion’s share of my high school physics classes were spent exploring the mischievous potential of the humble Bunsen burner instead of paying attention. An unwavering dedication to misadventure allowed me to fashion a crude flamethrower – an innovation rewarded with a hefty punny rather than a Nobel – yet its abiding legacy is a shameful ignorance.

I can appreciate that scientific endeavour is the engine of prosperity, a light that keeps us from the dark, but until recently, I viewed it only in terms of its applications – the technological and medical innovations that others forge from science’s grand designs. The science itself was subordinate, a impenetrable web that seemed to prize mathematics over concepts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was only a few months back, writing a story about the work of University of Glasgow researchers involved a project known as Lisa Pathfinder, that I had my own eureka moment while reading about Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

It was a century ago this evening that Einstein, aged just 36, took to the stage of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin and changed the way we view the world forever. The culmination of four lectures, each given a week apart, the address was entitled “The Field Equations of Gravitation”, and presented a unifying framework for gravity and his relativistic ideas of space and time.

By any empirical measure, it is the most important intellectual breakthrough in the history of mankind, a foundational edifice woven into the mesh of our lives which continues to give up its secrets.

Instead of occupying just three spatial dimensions, Einstein understood objects also exist in time as part of a continuum, where gravity – far from being an instantaneous force – was a warp in its knitted fabric. While Newton explained the earth’s orbit around the sun in terms of a vast object tugging at smaller one, Einstein dismissed the idea of space as an immutable stage.

He likened his metric theory of gravitation to placing a bowling ball, and then a few pool balls, on to the surface of a trampoline. It was not gravity that beckoned the smaller balls closer, he reasoned, but the curvature of the sagging fabric.

With one analogy, he communicated the interplay between motion, matter and energy in terms so lucid, it piqued my inchoate interest in physics. It was not the magnitude of Einstein’s discovery that struck me, rather the means by which he arrived at it.

From an early age, the German realised the most fruitful laboratory of all was his imagination, a place where visuals and ideas could coalesce and broach new proposals. At 16, he toyed with the theory laid down by James Clerk Maxwell, wondering what a beam of light would be like were he to ride alongside it.

The idea would provide a pathway to special relativity and cemented his fame, though it was another thought experiment that assured him of immortality when, sitting at his desk at the patent office in Berne in 1907, he pictured a painter falling from a roof.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDuring the descent, Einstein realised, the man would not feel his own weight. It was, he would recall, “the happiest thought of my life”, a thread of truth that would guide him to the realisation of the general theory eight years later.

It is these examples of Einstein’s Gedankenexperiment – thought experiments – that set him apart. Here was a relatable means of probing the exceptional mysteries of our universe through conceptualisations, a technique that depended on fancy as much as formulae.

Mathematics may be the language employed to translate nature’s opaque wonders, but Einstein understood it was creativity that unlocked truly transformative ideas. His was a mind that did not search for solutions to problems, but proposed new ways of looking at the world around us. His decade-long quest towards the theory was sparked not by some unexplained observation, only the desire to simplify what we already knew.

The paragon of Einstein’s erudition has stubbornly denied all who seek to debunk and negate it, a theory so perfect even its creator could not have predicted its boundless implications. From the study of black holes and supernovae to questions about the origins of the universe, it serves as a compass, shepherding new generations of pioneers towards uncharted truths.

Lisa Pathfinder is just the latest example. A week today, its satellite will be launched into orbit, the first step of a mission to track the relative movement of two small gold-platinum blocks put into a near perfect freefall. In doing so, it will seek to verify the general relativity theory’s last unproven predication – the existence of gravitational waves, ripples in space-time caused by violent cosmic events like the explosion of dying stars.

The expertise behind the £295m initiative is considerable, yet to my mind, what is most remarkable is the fact the entire project is predicated on that fateful Berne daydream.

This is Einstein’s most potent gift, the one that keeps giving; his ability to express genius in ingenuous ways. It is a form of art as much science and the man himself articulated it best during a lecture in Glasgow in 1933, informing a rapt audience of his “years of searching in the dark for a truth that one feels but cannot express”.

Einstein was the first to admit that there were more capable mathematicians among his peers. No one before or since, however, has demonstrated the same intuitive curiosity of life’s great generalities coupled with the ability to wrest them into a form intelligible to the everyman.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe past century is his century and we should consider ourselves fortunate to have lived through it. His was a mind that could discern the invisible. Even those of us who failed our physics exams can see that.