Lori Anderson: UK opening door for designer babies

I have donned my condemnatory garb because I feel it is necessary to denounce the duplicity of the British Government. I choose my words with care because what I believe they are doing is deliberately trying to dupe the public into believing something is not what it most certainly is: the genetic modification of human embryos.

Britain is set to become the first country in the world to legalise the modification of human embryos. For many years the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) deemed it illegal, as it is everywhere else in the world, to alter the nuclear or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of eggs, sperm or embryos then place them back into a woman’s body.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe reason the HFEA has changed its mind is not to save a single life but to ensure that each year a dozen or so women will be able to have a genetic link to a healthy child. For women who have faulty mtDNA there is the risk of giving birth to a child who is likely to suffer neurodegenerative diseases such as blindness, muscular dystrophy, diabetes and deafness. In Britain each year, around 200 babies (one in 6,500) are affected by mitochondrial disease. The current options for women with faulty mtDNA are to either adopt or opt for embryo donation or egg donation. The latter would allow their male partner to “father” the child, but no existing option grants a genetic link for the mother.

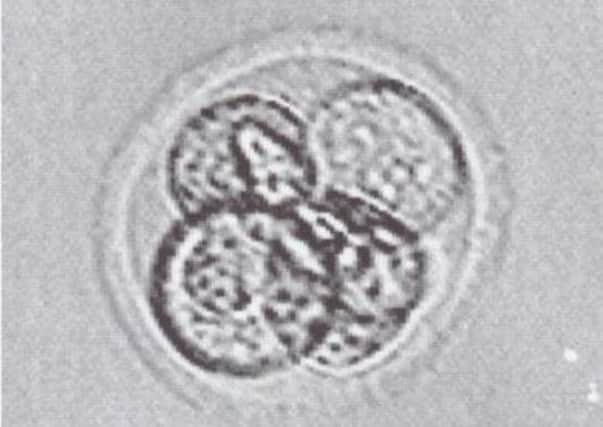

A new procedure, however, has been developed that would allow the mother to have that profound connection. It involves taking the one-day old pronuclei, created using the parent’s sperm and egg, and leaving behind the faulty mtDNA which comes from the cytoplasm in the mother’s egg. The pronuclei is then inserted into a second embryo, created from a donor with healthy mtDNA and the father’s sperm, after the donor/father’s pronuclei has been removed.

A child born from such a procedure would be unique in human history as they would have three genetic “parents”, though the DNA contribution from the donor would be tiny at just 0.2 per cent. This is because 25,000 genes come from the nuclear DNA of the mum and dad while just 13 genes come from the donor’s mtDNA, none of these genes is connected to physical traits or personal characteristics.

Yet what I find disturbing is, that if the child is a baby girl, her children will have the DNA characteristics of three parents, as will her daughter’s daughter and so on into the future. It is a decision that will affect future generations, and while there may be no health consequences, the fact is we just don’t know. Stuart Newman of New York Medical College has described this as: “full-scale germline genetic engineering”.

Those who support taking the first step over a line – which I believe will eventually lead us to a twisted world where parents can choose their child’s height and the colour of their eyes – agree that this is genetic modification but argue that it is worthwhile. Critics agree that it is genetic modification but that it will set a dangerous precedent. The only people who don’t think that the creation of children unique in human evolution with the DNA of three people instead of two is a form of genetic modification are the British Government.

Last month the Department of Health effectively re-wrote the definition of “genetic modification” to specifically exclude the alteration of human mitochondrial genes or any other genetic material that exists outside the chromosomes in the nucleus of the cell. The reason for doing this is that it believes it will be easier to sell such an advancement to the public if it can insist that the end result will not be a “GM baby”. In a statement released a few weeks ago the Department of Health compared this seismic change in policy to donating blood. It stated: “There is no universally agreed definition of ‘genetic modification’ in humans – people who have organ transplants, blood donations, or even gene therapy are not generally regarded as being ‘genetically modified’. The Government has decided to adopt a working definition for the purpose of taking forward these regulations.”

Even supporters of the new fertility treatment such as Lord Winston now argue that the Government is being dishonest. He said: “Of course mitochondrial transfer is genetic modification and this modification is handed down the generations. It is totally wrong to compare it with a blood transfusion or a transplant and an honest statement might be more sensible and encourage public trust.”

We don’t know what dark and murky waters this medical development may lead to in future generations, so the least the government can do at the outset is to be clear.