Lori Anderson: Enduring appeal of self-help guides

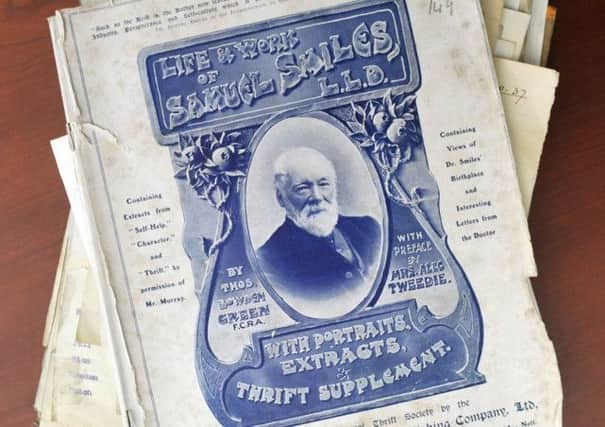

Last year was the year of the utterly sickening selfie. Social media has been crammed full with reincarnations of Narcissus and Snow White’s evil stepmother bewitched by the vanity of their iPhones. Can selfies be redeemed? Yes, and I know just the man to whom we should turn. It’s a pity that he’s been dead for 110 years but the wisdom of Samuel Smiles is eternal and has never been in greater demand than in the cold, bleak chill of January.

Samuel Smiles was nominally born in Haddington to be an optimist. But fear not, we are not talking about any of that transatlantic hee haw – we are still Scots after all, we have standards – instead he invented the modern self-help book.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne of 11 children, Smiles trained as a doctor at Edinburgh University before switching to journalism and moving south to edit the Leeds Times. A practitioner of hauling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps, Smiles would have admired Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American transcendentalist whose essay “Self Reliance” was published in 1841. Smiles made his own literary contribution in 1859 with the publication of Self-Help. The book advocated personal prudence and industry as the key to self-improvement and sold 20,000 copies in the first year to enthusiastic Victorians, and a total of 200,000 before he died in 1904.

Were he alive today, Samuel Smiles would be pleased to see that the self-help book appears to have come of age. Today marks the paperback launch of one of last year’s surprise bestsellers, The Examined Life: How We Lose and Find Ourselves by Stephen Grosz, a British psychoanalyst who whittled 25 years and 50,000 hours of couch conversations with patients into a gripping and illuminating read.

This month, the publisher Vintage will also release a series of 12 books designed to make us better, more focused and more contented individuals, all under the witty title Shelf Help. Among the chosen texts are Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, a memoir by Jeanette Winterson; Nothing to be Frightened Of by Julian Barnes, a meditation on death; and Andrew Solomon’s hefty study of the family, Far from the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity.

Jessica Lamb-Shapiro has written a book, Promise Land: My Journey Through America’s Self-Help Culture, which analysed the £7 billion industry of books and improvement courses and found it was in rude health. She said: “While there may be plenty of derision for today’s self-help books, they are part of an ever-expanding self-betterment market showing no signs of neglect.”

She points out an interesting statistic, which is that 80 per cent of people who buy self-help books have bought previous self-help books, “which could indicate that they are not helping”. Yet there have been studies which show that they are better than nothing. A team of researchers at the University of Arizona found that sufferers of depression or panic disorders did benefit from certain self-help books, but not as much as those who embarked on psychotherapy.

Last year, Canongate Books in Edinburgh published The Novel Cure: An A to Z of Literary Remedies by Susan Elderkin and Ella Berthoud, which offered sage advice on everything from apathy (with notes by James M Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice) to fatherhood (see Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road). In December, Berthoud held a seminar in Edinburgh on bibliotherapy, or how the right book at the right time can chase away the blues or help one come to terms with problems or disappointment. It has always been so. Man’s perpetual need for reassurance, guidance and assistance has meant that self-help books are far older than the printing press that churns them out. The works of the Ancient Greek philosophers, written on scrolls, were often viewed as literary balms for the soul. As Epicurus said: “Any philosopher’s argument which does not therapeutically treat human suffering is worthless; for just as there is no profit in medicine when it doesn’t expel the diseases of the body, so there is no profit in philosophy when it doesn’t expel the sufferings of the mind.” This is why Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic remains a popular title 2,000 years after the Roman philosopher first put quill to parchment, as does Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which were written in the second century AD.

In the Middle Ages, the second most popular book, laboriously copied out by monks as an illuminated text, was Consolation of Philosophy, a guide to coping with sickness, death and the unfairness of life written by Boethius, a sixth-century consul who knew of what he wrote – he penned the manuscript while under sentence of death by King Theodoric the Great. The “new wave” of erudite self-help books can be traced back to 2000, when Alain de Botton mined the great thinkers of the past for his book The Consolations of Philosophy, a tugged forelock towards Boethius.

Self-help books will always be with us, but while we may seek them out for assistance, the evidence is that we rarely do as we are told. But think how much better our year will be if we act upon Samuel Smile’s sage advice in Self-Help: “The spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual…The object of the book briefly is, to re-inculcate these old-fashioned but wholesome lessons – which perhaps cannot be too often urged – that youth must work in order to enjoy; that nothing creditable can be accomplished without application and diligence; that the student must not be daunted by difficulties, but conquer them by patience and perseverance; and that, above all, he must seek elevation of character, without which capacity is worthless and worldly success is naught.”