Lesley Riddoch: Me Too movements should embrace Scotland's '˜witches'

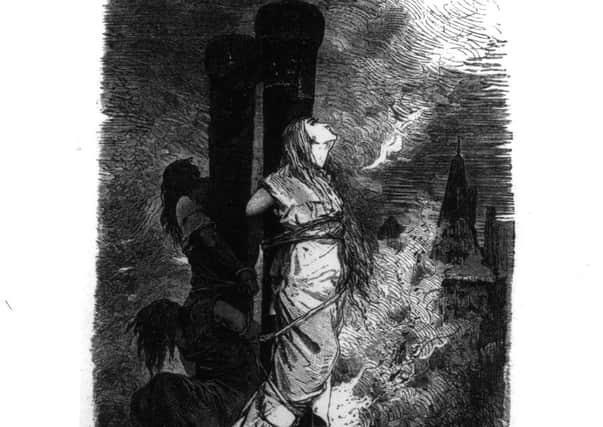

How can a weekend of spooky fun be “inspired” by the gruesome killing of seven people, whose only crimes appear to have been using herbal remedies and forecasting the weather by studying bird movements and cattle behaviour? Four female and two male “witches” were strangled on Paisley Gallow Green in 1697, (another man committed suicide in prison.) Their bodies were burned and charred remains buried at a site still marked by a circle of cobbled stones.

Not very funny. They’d been found guilty of putting a spell on 11-year-old Christian Shaw, the daughter of a wealthy local laird - to this day, there’s more interest in whether the attention-seeking child really was to blame. A minor historical detail still over-shadows the horror of seven unjust deaths? Why?

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIs it not possible for modern Scots to empathise – to think about the horror of the situation? Seven people, facing horrible deaths over entirely groundless accusations - can we not imagine the terror?

Now to be fair, the Paisley event seems to have been a joyful festival with a Mardi Gras atmosphere, acrobats, hundreds of youngsters in brightly coloured costumes and mercifully few witches’ hats or broomsticks. But that flippant and facile connection between strangulation and fun, in every radio interview and press article means I, for one, have no urge to attend.

Mention of witches still prompts a wee titter and immediate association with Harry Potter, broomsticks and crooked noses. Not the 3837 people accused of witchcraft in Scotland between 1565 and 1735. According to historians Lauren Martin and Joyce Miller in their exhaustive study ‘The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’ 67 per cent of them were executed, 85 per cent were women and almost all were tortured.

Of course, that’s disputed. Women were not generally placed in the “boots,” “rack” or thumbscrews. Edinburgh woman Agnes Sampson was shackled to her cell wall and stabbed in the face with a four-pronged iron fork, which pierced through her cheeks and tongue – after being accused of plotting to kill King James VI in 1590. But most suspected witches were “only” stripped naked and shaved of all hair including pubic hair to look for “devil’s marks” which were pricked with pins to find insensitive skin “proving” guilt. The idea of being touched, prodded and intimately examined by strange men must have been terrifying. The women were then kept awake for days and “encouraged” to confess.

A similar witch trial took place at Tullibole Castle near the Crook of Devon in Kinross, home to William Halliday and his son John in 1662. They held court over ‘covens’ in the village and ordered 11 suspected witches to be strangled and burned. Rosie Hopkins lives near the old execution site and has researched the trials. She says; “The women and one man were kept in solitary and in the dark. There is no record of any defence or appeals. That’s how disenfranchised these women were. When they were strangled, every villager was required to watch. The humiliation and terror is still alive and meaningful to me.”

Quite. I’m sure I’m not the only mouthy woman looking at these trials thinking, there but for the passage of time, go I. Or, to use a more modern idiom - “Me Too.”

It’s important to tease out links between modern women and “witches” of yesteryear because the idea that most were old, poor, disabled or odd is just plain wrong. The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft found 64 per cent of accused women came from “middle range” homes. Few were lonely spinsters or widows – 78 per cent were actually married - but almost all were confident, outspoken and assertive. This is what caused offence. As historian Louise Yeoman puts it;

“The average witch lived in a small borough town. She had an occupation and brought money into the home in her own right. She had a sharp tongue and might have fallen out with neighbours – in other words, she was us.”

This matters.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite its relatively small population, Scotland was Europe’s biggest persecutor of witches. King James VI’s personal obsession meant Scottish “witch-finders” were also sent abroad. They burned and killed hundreds of Sami men and women in Arctic Norway – a memorial to those victims was unveiled in 2011 by Norway’s Queen Sonja.

But there’s been no similar recognition or rehabilitation here. A site at the entrance to Edinburgh Castle’s esplanade, commemorates the place where Agnes Sampson and three hundred other women were strangled and burned for being witches in 1591. A plaque beside a fountain reads “The wicked head and serene head signify that some (witches) used their exceptional knowledge for evil while others... wished their kind nothing but good.”

This of course is nonsense. Scottish society stopped believing in the powers of witchcraft 250 years ago, so no “wicked head” passing within inches of this plaque during its last terrified minutes on this earth could possibly have committed harm by thought or speech alone. Yet the plaque remains.

Ten years ago, a campaign to pardon Scotland’s “witches” was rejected by Holyrood’s petitions committee because they felt it was wrong to excuse people found guilty under laws of their own time and “difficult to apply modern concepts of knowledge and morality to centuries past”.

Really? Earlier this year, thousands of gay and bisexual men prosecuted for having sex under old laws, were quite rightly pardoned by a unanimous vote in the Scottish Parliament. The slur on the reputation of the women slaughtered centuries back is essentially no different.

As it is, the refusal to recognise witchcraft as the unjust persecution of (mostly) women means new generations of well-meaning folk are able to ignore the pain, terror and persecution of witch trials and find the quasi-judicial lynching of outspoken women somehow inspiring. But why should the organisers of Paisley’s Halloween Festival recognise this shameful aspect of our history when officialdom in Scotland hardly cares?

Perhaps next year, Paisley can lead Scotland in respectful commemoration of its persecuted women and ensure that forgotten acts of misogyny don’t get packaged into selling opportunities for black hats, broomsticks and detachable warts at Halloween.