Leaders: Penrose inquiry lessons must be learned

The questions that need to be asked in cases like these are urgent and important. What went wrong? Who or what was responsible? And what can be done to prevent it from happening again?

Thoroughness and speed are of the essence. And yet all too often official inquiries provide the former but not the latter.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

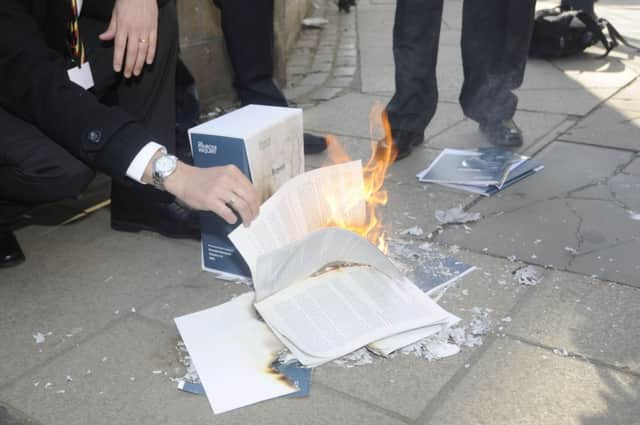

Hide AdThe Penrose inquiry into blood contamination in the NHS, which reported yesterday, is a case in point.

It was certainly thorough, costing £11.3 million in legal and administrative fees.

But speedy it was not. It took six years to sift through all the evidence and come to its slim conclusions.

The actual errors that led to the contamination of blood products were long ago corrected. The officials who made the errors have long since departed their posts. And the lessons to prevent any such errors happening again have been pretty comprehensively learned.

They had to be. Action needed to be swift and comprehensive to protect patient safety.

Which is why it should not perhaps be a surprise that the practical recommendations from Lord Penrose yesterday were so brief and – according to critics – perfunctory.

The human stories behind the Penrose inquiry are tragic and upsetting. Lives were irrevocably changed because of administrative failings, and the victims and their families have been justly angry that a system which is built to care could have been so tragically flawed.

But there has clearly been a mismatch between the victims’ expectations of this inquiry and what Lord Penrose felt it was possible to deliver within his remit. The victims felt individuals should have been identified and held responsible, but Lord Penrose’s conclusions took a measured view on some of the flawed decisions taken by officials who were working without the benefit of hindsight now available to us.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdTheir decisions had to be examined by the standards of the time, he insisted.

This seems reasonable. Anything else would stand the risk of being unjustly punitive on officials who were acting in good faith.

The question remains whether this protracted and expensive inquiry process has done all that much to advance our knowledge and help protect patients in the here and now.

This is worthy of examination by ministers. An inquiry into inquiries may seem like a perverse joke.

But some serious thought has to be given to whether the accepted way of dealing with such scenarios is sufficient for its purpose.

Strike up the bandstand

IT IS potentially one of the UK’s most iconic venues. The Ross Bandstand sits in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle, in a ribbon of beautiful gardens, slap bang in the middle of one of Europe’s great capital cities.

And yet the bandstand is in poor repair, recently described by one rock promoter as looking like a “bombed-out shelter”.

A wasted opportunity, if ever there was one.

Into this somewhat depressing scenario steps Norman Springford, founder of the Apex Hotels group and a former owner of the Edinburgh Playhouse, with an offer to plough several million pounds into the creation of a brand new venue on the site to bring world-class concerts to Princes Street.

This is a superb offer, to be heartily welcomed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhat is particularly impressive is Mr Springford’s ambition and boldness, citing the Guggenheim in Bilbao as an inspiration.

Scotland has a proud history of arts philanthropy, from the theatres built by Andrew Carnegie – like Edinburgh’s King’s Theatre – through to the extension to the National Galleries of Scotland on The Mound, partly financed by an array of the nation’s most prominent industrialists and tycoons.

Philanthropy is much more common in the US than it is in this country. In the States, an accepted part of having money is thinking of philanthropic ways of getting rid of it.

That mindset is catching on here too, and Scots are in the forefront of the trend, with causes earning support ranging from third world development (a particular focus of Sir Tom Hunter) to health research (championed by JK Rowling).

Mr Springford is in good company indeed.

FOLLOW US

SCOTSMAN TABLET AND MOBILE APPS