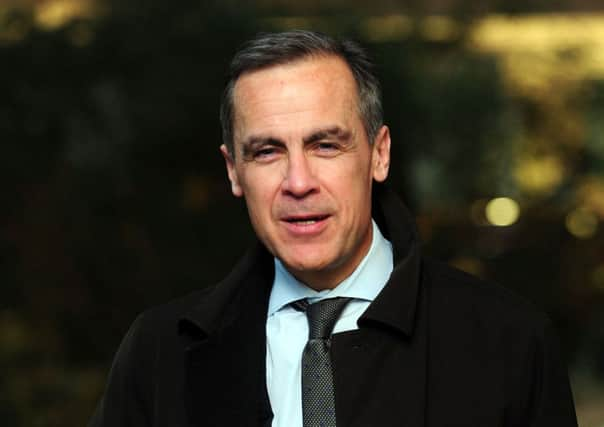

Leaders: Mark Carney | White paper cost

Montagu Norman, the most influential governor of the 20th century, went as far as travelling under a false name in order to avoid the media. These days, the fashion is for just the opposite. The new Governor of the Bank of England, Canadian Mark Carney, believes in the doctrine of “forward guidance”: telling everyone well in advance what he intends to do with interest rates and the economy.

There is much to be said for this new, open approach. Investing long-term becomes less risky, helping economic growth. However, we are now discovering there is a downside to Governors of the Bank of England taking on a more public role. Last summer, Mr Carney pledged not to raise interest rates while unemployment remained above 7 per cent. Six months later, with unemployment falling faster than expected, he has been forced to “clarify” that unemployment was only one indicator that would determine interest rates. The Governor’s change of emphasis was welcomed by mortgage payers, but it proves that he is fallible. And fallibility is not what central bankers should be – at least not too often.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnfortunately, the more Mr Carney speaks in public, the more he invites controversy. Last month he was in Scotland making a speech on the pros and cons of a possible sterling currency zone if Scotland votes for independence. Arguably, it was an excellent speech and helped clear the air on a subject surrounded by political fog. He pulled no punches in warning Scotland would have to surrender a significant degree of sovereignty if it wants a currency union. It is a warning the Yes camp needs to heed.

However, the Governor is on weaker ground when he strays into matters in which – as a professional economist – he is less well-versed. Yesterday, answering questions before the Commons Treasury committee, he ventured that it is “a distinct possibility” RBS would have to move head office to the remainder of the UK (rUK), in the event of independence. He was rather unclear on why this might be the case, referring obliquely to European Union directives that require a bank to have its corporate HQ and de facto registered office in the same country.

However, the European Commission directive on which he bases his contention has never been tested, and is full of legal holes. More to the point, it helps no-one – and is hardly good for the RBS share price – for a Governor of the Bank of England to make unsupported remarks regarding the location of a major bank. That is not his job nor his area of expertise. Speculating on Scotland joining Europe comes in to the same category. Perhaps, after all, there are occasions when reticence is still a good idea for central bankers.

White paper is a price worth paying

HOW much is democracy worth? For decades, politicians seeking votes and vested interest groups demanding subsidies have combined to fleece the taxpayer. As a result – and rightly – every penny of public spending is now carefully scrutinised for value. So it is perfectly proper to question how much the Scottish Government has spent on the white paper on independence, published last November. The answer is £1.25 million and counting. Jackson Carlaw, the Conservative MSP, calls this “ridiculous”. However, we think he is wrong. In this instance, democracy is worth the expense.

Scottish voters are unlikely ever in their lifetimes to make a decision as momentous as they will do on 18 September. They deserve to be well-informed on the constitutional question. The time has come to resolve it. That is worth paying for. Voters have requested more than 100,000 copies of the white paper. There may be doubts about the document but it spells out what the Scottish Government thinks and that in itself is of great value. It is only common sense, now the document exists, that it should go to as many people as possible. Besides, the coalition government at Westminster has spent a significant amount of money and civil service time producing its own contributions to the debate. At last count, the UK Treasury has published 15 long documents “to inform the debate about Scotland’s constitutional future”. That effort, too, is worth the cost.

Public money should never be wasted and there is a limit to propaganda at the taxpayers’ expense. Equally, we cannot have a constitutional debate of substance without detailed information. That has to be paid for.